James Leipold served as the executive director of NALP (National Association for Law Placement) for over 18 years. He now works as a senior advisor with the Law School Admission Council (LSAC). Leipold wrote a thorough review of Neil Hamilton’s Third Edition of the award-winning book, Roadmap: The Law Student’s Guide to Meaningful Employment, published by the ABA. Leipold’s detailed and insightful review can be found here.

Clinics

An Unexpected Synergy: How Integrating Professional Identity Formation Exercises in a Civil Procedure Course Not Only Help Students Form a Professional Identity but Also Enhance Their Understanding of Civil Procedure

By: David A. Grenardo, Professor of Law and Associate Director of the Holloran Center for Ethical Leadership in the Professions, University of St. Thomas School of Law

Professor Benjamin V. Madison III, Professor of Law and Director of the Center for Professional Formation at Regent University School of Law, authored a pretrial practice casebook, Civil Procedure for All States: A Context and Practice Casebook, which was one of the first casebooks that explicitly and intentionally incorporated professional identity formation as recommended by the Carnegie Institute study Educating Lawyers (2007). Madison presented at the University of St. Thomas Law Journal’s spring 2023 symposium, which brought together 1L and Professional Responsibility casebook authors to discuss how they infuse professional identity formation into the required curriculum. Madison’s latest article, An Unexpected Synergy: How Integrating Professional Identity Formation Exercises in a Civil Procedure Course Not Only Help Students Form a Professional Identity but Also Enhance Their Understanding of Civil Procedure, will be part of that symposium’s issue.

Here is the abstract of the article:

This article demonstrates that integrating professional identity formation exercises in a required course accomplishes multiple goals. The Carnegie report stated, “[l]egal analysis alone is only a partial foundation for developing professional competence and identity.” The report was clear that only the formation of values and the ability to exercise moral judgment would allow students to practice as true professionals. Both first-year and advanced civil procedure courses feature professional identity formation exercises. They present dilemmas litigators face, particularly ones that the Model Rules of Professional Conduct do not answer.

The article describes how the effectiveness of the exercises improved depending on how the professor assigned them. When students read the exercises and discussed them in class, along with cases and other reading, students showed less engagement in the complexity of moral and ethical questions. Conversely, when students wrote reflection papers on the exercises due before the class discussion, they displayed greater discernment than when students did not write reflections. After writing about the exercise, more students recognized that reflective lawyers balance multiple interests and the lawyer’s values in resolving an ethical/moral challenge. The examples explored in the article, as representative of the type of exercises, include various issues that arise in handling a civil suit. The sample exercises include a choice-of-forum decision, a client’s request to serve a defendant in a specific manner, and two discovery scenarios. The first discovery scenario depicts a lawyer deciding whether to set a trial and other deadlines later than necessary and how that affects the client, not to mention the lawyer’s financial gain if on a billable hour engagement. The second discovery example demonstrates efforts to use excessive production of documents to increase the chance that the discovering party misses key documents.

The benefits of the exercises were two-fold. As a routine, graded part of the course, students gained an appreciation for moral and ethical judgments not answered by the Model Rules. The courses’ learning objectives state that by engaging in the exercises, students would develop a professional identity that includes values and a moral compass that will answer questions not addressed by the Model Rules. Therefore, students cultivate values, a moral compass, and the ability to resolve dilemmas they will likely face in practice. An additional benefit was the improved grasp of the rules and doctrines connected to the scenarios. Although intended to promote professional identity development, the exercises also reinforced knowledge of the rules and doctrines that formed the context for the exercises. Hence, students learned these rules and doctrines better than if the exercise were left out.

A link to the article can be found here.

Should you have any questions or comments about the article, please feel free to contact Professor Madison at benjmad@regent.edu.

Breaking Down Siloes and Building Up Students: The Transformational Possibilities of Professional Identity Formation

By: David A. Grenardo, Professor of Law and Associate Director of the Holloran Center for Ethical Leadership in the Professions, University of St. Thomas School of Law

Three national leaders in professional identity formation—Lindsey P. Gustafson, Aric K. Short, and Robin Thorner—came together to author an exceptional article focused on professional identity formation. Their article, Breaking Down Siloes and Building Up Students: The Transformational Possibilities of Professional Identity Formation, will be part of the University of St. Thomas Law Journal’s spring 2023 symposium issue that will explore pedagogies relating to professional identity formation.

Here is the abstract of the article:

Under the ABA’s sequenced approach to implementation of Standard 303(b)(3), schools should now have developed plans for providing opportunities for professional identity formation and should be implementing them. These plans must provide students with an “intentional exploration of the values, guiding principles, and well-being practices considered foundational to successful legal practice.” In addition, these plans should provide for frequent opportunities for development, “during each year of law school and in a variety of courses and co-curricular and professional development activities.”

Because Standard 303(b)(3) is necessarily tied to the unique character, existing structures, and available resources of a law school, each school’s plan will be different. That has been our experience as we have worked as professional identity formation leaders in different roles with varying perspectives: Lindsey Gustafson at the William H. Bowen School of Law, University of Arkansas at Little Rock, is a current Associate Dean for Academic Affairs and a skills and doctrinal professor; Aric Short at the Texas A&M School of Law is a former Associate Dean for Academic Affairs, a doctrinal professor, and currently serves as the Director of the Professionalism and Leadership Program; and Robin Thorner at St. Mary’s University School of Law is an Assistant Dean for Career Strategy, a teaching adjunct, and the current Director of Professional Identity Formation.

In this essay, we hope to emphasize that professional identity formation efforts can occur all across the law school’s operations, from administrative offices to classrooms to voluntary student activities. We also provide specific examples of how schools can be more intentional and explicit as they weave together multiple professional identity formation opportunities for their students. This process takes time and attention, but it creates a powerful whole-building approach to identity formation that not only complies with 303(b)(3), but also best positions our students for a successful, fulfilling, and impactful career in law.

A link to the article can be found here.

Should you have any questions or comments about the article, please feel free to contact any or all of the authors at lpgustafson@ualr.edu, ashort@law.tamu.edu, and rthorner@stmarytx.edu.

Professional Responsibility and Professional Identity Formation in a Community of Practice with Alumni

By: David A. Grenardo, Professor of Law and Associate Director of the Holloran Center for Ethical Leadership in the Professions, University of St. Thomas School of Law

Every time a bell rings, an angel gets its wings…and Neil Hamilton finishes another article. Neil Hamilton, the Holloran Professor of Law and Co-Director of the Holloran Center for Ethical Leadership in the Professions at the University of St. Thomas School of Law, has completed a new professional identity formation article. Hamilton wrote his latest article for the University of St. Thomas Law Journal’s spring 2023 symposium on professional identity formation. Hamilton’s article explores a new approach to the required Professional Responsibility course that provides reasonable coverage of the law of lawyering, legal analysis, and compliance, but also helps each student understand and participate in a community of practice focused on all the discretionary calls of lawyering in the area of the student’s ultimate practice interest. The student sees that legal ethics knowledge and capacities are not just doctrinal knowledge and legal analysis but are also social and situated in a community of practice. The student also sees that many alumni of the law school are successful in the practice of law while living into the values of the law school and the profession, not just compliance with the minimum floor of the law of lawyering. The student will also understand that in any practice area, the experienced lawyers know who can be trusted and who are the jerks. It will be the student’s and new lawyer’s choice which path to take.

Part II(A) of the article first outlines that the ABA Model Rules of Professional Responsibility (adopted by all 50 states with some variation) codify some values of the profession (like competence, diligence, confidentiality, and loyalty) into the law of lawyering with which licensed lawyers must comply. Part II(A) also explains that many of the Rules give discretion to practicing lawyers with respect to choices about conduct above the floor of the Rules. Part II(B) then analyzes the core values in the mission and learning outcomes of some law schools, and in the Preamble to the Model Rules, that help guide each lawyer’s discretionary decision-making. Part III analyzes how communities of practice influence lawyers in making the discretionary calls of lawyering in a way consistent with the profession’s core values. Part IV explores empirical evidence on whether practicing lawyers think their legal education was an effective community of practice fostering their understanding of these core values in making the discretionary calls of lawyering. Part V discusses Hamilton’s own Professional Responsibility course that creates communities of practice with students and alumni to help students understand the importance of the law school’s and the profession’s core values in making the discretionary calls of lawyering.

A link to Hamilton’s article can be found here.

David Grenardo is a Professor of Law and Associate Director of the Holloran Center for Ethical Leadership in the Professions at the University of St. Thomas School of Law.

INTRODUCING THE STREAMLINED (AND EVEN MORE LAW-STUDENT FRIENDLY) THIRD EDITION OF NEIL HAMILTON’S AWARD-WINNING BOOK, ROADMAP: THE LAW STUDENT’S GUIDE TO MEANINGFUL EMPLOYMENT (2023)

By: Neil Hamilton, Holloran Professor of Law and Co-Director of the Holloran Center for Ethical Leadership in the Professions, University of St. Thomas School of Law

The learning outcome for the ROADMAP is that each student takes ownership (self-direction) over the student’s professional development toward the student’s goals of bar passage and meaningful post-graduation employment. Students at later stages of self-direction demonstrate higher academic performance and planning and implementation skills that increase bar passage and post-graduation employment outcomes. The ROADMAP is empowering each student to perform at the student’s highest capacity. The ROADMAP is also meeting ABA Standard 303(b) and (c) requirements regarding the development of each student’s professional identity.

This third edition of the ROADMAP is a complete revision of the second edition. Since the first edition was published in 2015, and the second edition in 2018, the Holloran Center and I have continued to learn how more effectively to go where the students are developmentally to help them achieve their goals (and the Law School’s goals) of bar passage and meaningful post-graduation employment.

The entire book is now 50 pages at a price of $19.95 (ABA’s website indicates ordered books will ship on August 15 at the earliest). In this edition, the students read 21 pages and then do the template plan which is 5 pages. The reading and the template plan focus on using the student’s time inside and outside of the building to gain experiences that will achieve three goals:

- Thoughtfully discern the student’s passion, motivating interests, and strengths that best fit with a geographic community of practice, a practice area and type of client, and type of employer;

- Develop the student’s strengths to the next level; and

- Demonstrate evidence of the student’s strengths that employers value.

The book then has a chapter on building a tent of professional relationships that helps each student achieve these three goals plus a professional relationship tent-building template plan. This chapter also includes cross-cultural skills addressing ABA Standard 303(c).

A number of law schools already use the ROADMAP, and the hope is that other law schools will discover its incredible value in helping law students with their professional identity formation. To discover what the ROADMAP can do for your law students, you can find the book here.

Neil Hamilton is the Holloran Professor of Law and Co-Director of the Holloran Center for Ethical Leadership in the Professions at the University of St. Thomas School of Law in Minnesota.

By: Linda Sugin, Professor of Law & Faculty Director for the Office of Professionalism, Fordham Law School

The three-part series published in the National Law Journal, “Does Law School Have to Suck?,” analyzes seven reasons why law students are unhappy. In the series, I also propose changes that law schools and the legal profession should adopt to transform the student experience by reforming curriculum, assessment, hiring, and financing. The solutions advocated reflect two major themes – creating inclusive and supportive communities and individuating the development of professional identity for law students. These reforms would improve learning and help students build a wider range of capabilities necessary for professional success and satisfaction.

Here is a link to the three-part series published in the National Law Journal on March 30, April 4, and April 6, 2023. Feel free to contact me at lsugin@fordham.edu with questions or comments.

Linda Sugin is Professor of Law & Faculty Director for the Office of Professionalism at Fordham Law School in New York.

By: Kendall L. Kerew, Associate Clinical Professor of Law and Director of Externships, Georgia State University College of Law; Holloran Center Fellow

Last month, I had the privilege of participating in the 2023 Wake Forest Law Review Symposium: Leading Change in the Legal Profession.[1] I was part of a panel with Luke Bierman (Elon School of Law) and Maria Savasta-Kennedy (University of North Carolina School of Law) entitled, “Experiential Education and Lawyer Development.” Specifically, the panel “explore[d] the history of experiential education in law schools; the current status of experiential education in American legal education; and the role of experiential education, including clinics, externships, simulations, and more in shaping the professional identity of law students and lawyers.”[2]

Given the focus of the panel, my prepared remarks enumerated four reasons why experiential education should be central to how we teach law students now and in the future: 1) the requirement that law schools incorporate professional identity formation throughout the curriculum because learning while in the role of lawyer, where a student experiences the integration of knowledge, skills, and values, is particularly well-suited to examining one’s emerging professional identity;[3] 2) the requirement that law schools provide education on bias, cross-cultural competency, and racism because, for students in law clinics or field placements, one of the instances must occur before, concurrently with, or part of students’ enrollment in clinical or field placement courses;[4] 3) the development of the NextGen Bar Exam and efforts to ensure alternative pathways to licensure because the path forward is focused much less on rote memorization and more on the application of knowledge and skills;[5] and 4) the greater role artificial intelligence is likely to play in law practice because experiential education teaches lawyering skills that are uniquely human.

In this blog post, I want to focus on the last reason I posited for why experiential education is particularly relevant to the future of legal education: the greater role artificial intelligence is likely to play in law school and law practice. I am sure you have heard the news stories about ChatGPT writing passing answers to the bar exam and law school exams,[6] how ChatGPT can improve student legal writing,[7] how a judge used ChatGPT to write a ruling,[8] and that ChatGPT may end up making lawyers obsolete.[9] Given all the attention ChatGPT has been getting, I thought it would be interesting to ask ChatGPT the following question and share it as part of my remarks:

What aspects of lawyering cannot be replaced by AI?

This was ChatGPT’s response:

There are several aspects of lawyering that cannot be replaced by AI, including:

Empathy and Emotional Intelligence: Lawyers need to understand their clients’ emotions and needs to provide effective legal advice. AI lacks the ability to comprehend and express emotions, making it difficult for it to replace the empathy and emotional intelligence needed in the legal profession.

Creativity and Critical Thinking: Lawyers often need to come up with creative solutions to complex legal problems. AI, while capable of analyzing vast amounts of data and generating insights, lacks the creativity and critical thinking skills needed to approach legal issues in novel and effective ways.

Advocacy and Persuasion: A significant part of a lawyer’s role involves advocating for their clients’ interests in court or in negotiations. This requires excellent communication skills, the ability to read and respond to non-verbal cues, and the art of persuasion. While AI can analyze and predict the outcome of legal disputes, it cannot advocate for a client in a courtroom.

Ethics and Professionalism: Lawyers are bound by strict ethical and professional standards, which require them to act in the best interests of their clients while upholding the rule of law. AI lacks the moral compass and judgment necessary to make ethical decisions, making it unsuitable for replacing the role of a lawyer.

Client Relationship Management: A lawyer’s success often depends on their ability to build and maintain strong relationships with their clients. AI lacks the ability to build rapport or provide personalized attention to clients, making it difficult to replace the human touch needed in client relationship management.

If you are reading this blog, you probably already knew this and felt secure in the future of our profession. Nonetheless, ChatGPT’s answer encompasses the very things we teach in experiential education and explore through professional identity formation. So for this blog post, I decided to ask ChatGPT a follow-up question:

Why is professional identity formation important to legal education?

This was ChatGPT’s response:

Professional identity formation is essential to legal education because it shapes how law students understand themselves as future lawyers and how they approach their legal careers. A strong professional identity helps students to develop a sense of purpose and a commitment to the values and ethics of the legal profession.

Here are some key reasons why professional identity formation is important to legal education:

Ethical and Professional Conduct: A strong professional identity helps students develop a sense of responsibility towards ethical and professional conduct, which is essential for the effective functioning of the legal system.

Career Satisfaction: By developing a strong professional identity, law students can better understand their strengths and interests, and align them with the legal career path that is most fulfilling to them.

Client Relationships: A strong professional identity can help students develop the skills and mindset needed to build strong relationships with clients based on trust, integrity, and empathy.

Effective Advocacy: Professional identity formation can help law students develop the skills and values needed to be effective advocates for their clients, while still maintaining their own sense of professional ethics.

Overall, professional identity formation is an essential component of legal education, as it helps students develop the knowledge, skills, and values needed to become competent and ethical lawyers.

This response, coupled with ChatGPT’s response to my initial question, reinforced what we already know: professional identity formation is uniquely human and a necessary component of preparing law students to become the lawyers of the future – lawyers who cannot be replaced by artificial intelligence.

Please feel free to reach out to me at kkerew@gsu.edu if you have any questions or comments.

[1] http://www.wakeforestlawreview.com/2023-symposium/.

[3] See ABA Standards and Rules of Procedure for Approval of Law Schools 2022–2023, Standard 303(b)(3), https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/legal_education_and_admissions_to_the_bar/standards/2022-2023/2022-2023-standards-and-rules-of-procedure.pdf; Timothy W. Floyd & Kendall L. Kerew, Marking the Path from Law Student to Lawyer: Using Field Placement Courses to Facilitate the Deliberate Exploration of Professional Identity and Purpose, 68 Mercer L. Rev. 767, 790 (2017).

[4] See ABA Standards and Rules of Procedure for Approval of Law Schools 2022–2023, Standard 303(c), https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/legal_education_and_admissions_to_the_bar/standards/2022-2023/2022-2023-standards-and-rules-of-procedure.pdf.

[5] See About the NextGen Bar Exam, https://nextgenbarexam.ncbex.org/ (”Set to debut in July 2026, the NextGen Bar Exam will test on a broad range of foundational lawyering skills, utilizing a focused set of clearly identified fundamental legal concepts and principles needed in today’s practice of law.”).

[6] See Debra Cassesns Weiss, Latest version of ChatGPT aces bar exam with score nearing 90th Percentile, ABA Journal (March 16, 2023), https://www.abajournal.com/web/article/latest-version-of-chatgpt-aces-the-bar-exam-with-score-in-90th-percentile?utm_medium=email&utm_source=salesforce_642881&sc_sid=01075549&utm_campaign=weekly_email&promo=&utm_content=&additional4=&additional5=&sfmc_j=642881&sfmc_s=45062043&sfmc_l=1527&sfmc_jb=18001&sfmc_mid=100027443&sfmc_u=19035492.

[7] See Stephanie Francis Ward, Can ChatGPT help law students to write better? ABA Journal (March 6, 2023), https://www.abajournal.com/web/article/can-chatgpt-help-law-students-learn-to-write-better.

[8] See Columbian judge uses ChatGPT in ruling on child’s medical rights case, CBS News (Feb. 2, 2023), https://www.cbsnews.com/news/colombian-judge-uses-chatgpt-in-ruling-on-childs-medical-rights-case/.

[9] See Jenna Greene, Will ChatGPT make lawyers obsolete (Hint: be afraid), Reuters (Dec. 9, 2022), https://www.reuters.com/legal/transactional/will-chatgpt-make-lawyers-obsolete-hint-be-afraid-2022-12-09/.

THE “ONE FILE” COORDINATED COACHING INFORMATION SYSTEM: Developing a Robust Advising Management Application

By: Michael Robak, Director of the Schoenecker Law Library, Associate Dean, and Clinical Professor, University of St. Thomas School of Law

The concept behind developing a robust advising management application is to create “One File” of information developed by and about each student from the law school’s whole organization as the student moves through their law school career.

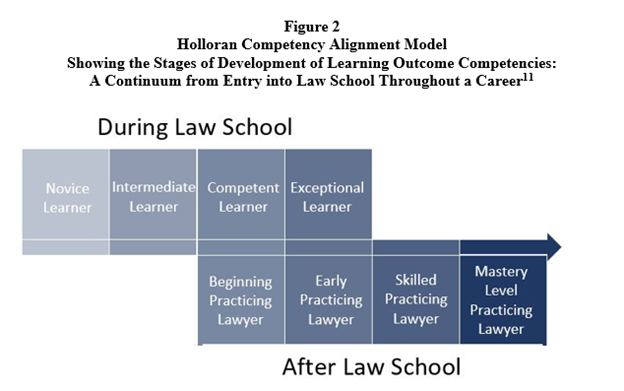

Collecting uniform information in one place, and allowing for appropriate organization-wide access will, we believe, create an advising mechanism that helps each law student move from novice to professional as described in the Holloran Center’s Competency Alignment Model. (Figure 2 below)

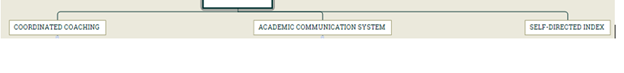

This information system is comprised of three elements:

The first element of this platform, Coordinated Coaching, will be used to capture information for each student from the nine coaching touch points that occur in their journey through law school as identified by Professors and Co-Directors of the Holloran Center Neil Hamilton and Jerry Organ. The Coordinated Coaching takes place at several points: (1) 1L Fall in a mandatory meeting with the Office of Career and Professional Development (CPD), which is described below in detail; (2) 1L Spring in a mandatory 1L class, Serving Clients Well, where professors, alumni, and local attorneys serve as coaches to the law students who work through Neil Hamilton’s award-winning Roadmap book regarding a student’s journey to finding meaningful employment; and (3) 2L and 3L years in the mandatory Mentor Externship program in which the professors teaching the classroom component of this program continue coaching and guiding the students. Capturing information from all of these contributors at these different times will allow for those coaching the students to coordinate to better assist student development of learning outcome competencies. Currently this information is captured and stored in multiple systems and trapped in organizational silos.

The second element of this platform is the Academic Communication System (ACS). We know, anecdotally, there are behavioral “red flags” which constitute potential clues (data points) for those at risk. The University of St. Thomas School of Law (“School of Law”) currently has nothing in place to serve as a tracking/communication platform for all the department administrators to record and share these interactions—the ACS would serve that function. The backbone of this element is key information for all students brought in from Banner. There are eight School of Law departments that would provide information into the system through twenty-three “Reporters” from across those organizations. [1] The first and most important interactions to capture are the ones with the Director of Academic Achievement and Bar Success as the Director is usually the first stop for students who have some academic success issues or concerns.

The third element of the platform, the Self-Directed Index, allows us to identify the students most at risk for possible problems with first-time bar passage and employment outcomes. While there is anecdotal evidence suggesting about 20% of students in any given year are at risk, we are seeking to fine tune that identification by developing an instrument to gauge an individual student’s self-directedness. This self-directed index would pull information primarily from Canvas. For example, one item of potential concern is class attendance. With the use of the Canvas attendance tracker, we could gather student information for each semester looking for patterns of activity. Another example includes tracking when students turn in their assignments? Are assignments submitted by students early, on time, or late? This is another variable we would be able to examine.

With these three platform elements in place, the One File system becomes the single source for capturing all the information about the student journey.

The Applications behind One File are Salesforce, Qualtrics, and Canvas. Salesforce will be customized for this specific project. Qualtrics will be used to capture the Coordinated Coaching and Academic Communication System information. The Self-Directed index will primarily rely on Canvas data.

Phase One of the One File system is putting parts of the Coordinated Coaching and Academic Communication System in place by the end of the Spring 2023 semester. For the Coordinated Coaching element, One File is “starting from scratch” with only the current 1L class; we are investing in the Class of 2025 as our beta group. We are not seeking to make One File retrospective for Coordinated Coaching.

At launch it will be built to hold the information for that Class’s 1L and 2L years. We would seek to add the 3L year sometime later in 2023 or early 2024. We have identified nine coaching touch points through the student’s law school journey for which we wish to track key information, and this first phase will track the first five touch points occurring in the 1L and 2L years. The last four touch points occur during the 3L year and are similar to the 2L year with the addition of a CPD exit interview and work for bar preparation through the JD Compass program.

Phase one development of the Academic Communication System will be built for our Director of Academic Success to capture the interactions with students. We anticipate broadening this to include other “Reporters” who can provide additional information to the file.

COORDINATED COACHING – the Beginning Touch Points

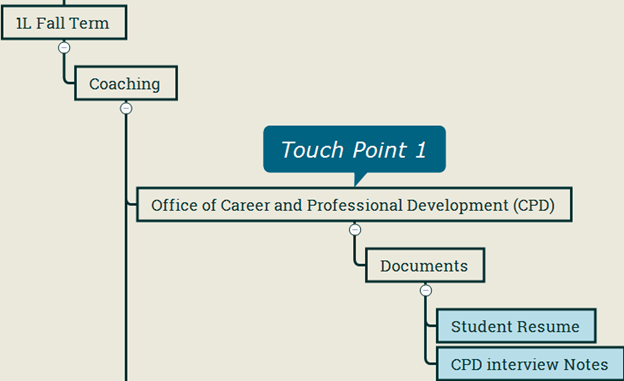

The first Coordinated Coaching touch point occurs during the 1L Fall term. Each 1L meets with a CPD team member, and this provides the initial (and base line) information about the student.

Coaching Touch Point 1:

Currently, CPD uses Symplicity for storing student resumes, as well as their meeting notes with students. In addition to the resume, the data we will capture in Salesforce for this touch point are:

CPD Meeting in First Year

- Practice Areas of Interest

- Geography of Interest

- Quick Assessment of Self-Directedness

These questions will be captured using a Qualtrics survey. The first two questions are answered by the students on their own or as part of the CPD meeting. The third question would need to be answered by CPD. We created a drop-down menu for the Practice Areas and Geography to create uniformity and consistency in the data gathered.

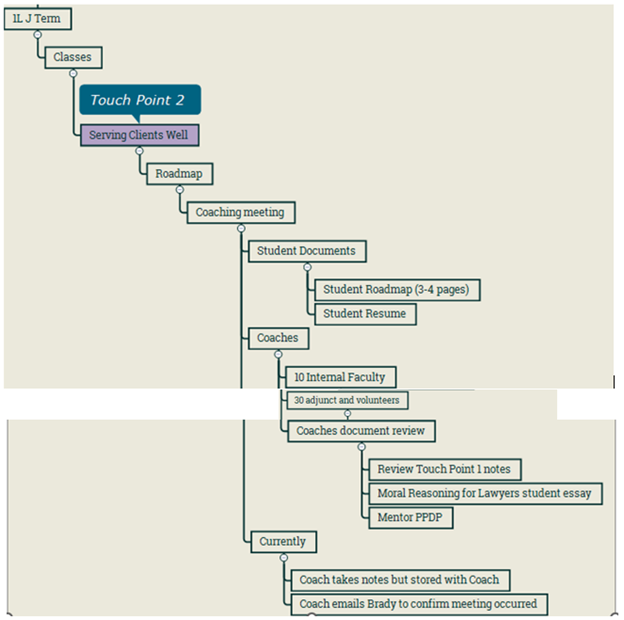

Coaching Touch Point 2: The second touch point, the Roadmap Coaching meeting, occurs early in the spring semester of the 1L year in conjunction with the Serving Clients Well class.

Prior to meeting with their Coach, the students create a student Roadmap and upload it to Canvas. The coaches have not had a single place to store the information they keep on their Coaching meetings with the students. In addition, two other documents have been created by the students, an essay written for the Moral Reasoning for Lawyers course and a Personal and Professional Development Plan written for the Mentor program. These documents, along with the completed student Roadmap template, will be placed in Salesforce and made available for review.

Qualtrics will be used for capturing the following data:

- Practice Areas of Interest

- Type of employer

- Geography of Interest

- Students self-identified and peer-affirmed strengths/competencies

- Quick Assessment of whether student understands concept of having to communicate a persuasive story of value and has good stories to tell

- Quick Assessment of Self-Directedness

- Identified goals for summer

- Identified interests for registration for next year

- Identified possible Mentor Experiences in which student is interested in next year

Again, we will be using drop downs to create uniform data capture.

This is a high-level overview of the One File system. Also, somewhat unique in the development of the application, we are not building the system all at one time. As mentioned earlier, we are starting with the School of Law Class of 2025 as the beginning point. We will be developing the system as that class moves through its law school career and then add the following incoming classes. In this way we can also learn as we develop the platform and allow for continuous improvement. We’ll have more to describe as we continue this journey.

If you have questions or comments, please reach out to me at michaelrobak@stthomas.edu.

Michael Robak is the Director of the Schoenecker Law Library, Associate Dean, and Clinical Professor at the University of St. Thomas School of Law.

[1] The Departments and Reporter count are as follows: Lawyering Skills (5 reporters), Academic Achievement and Bar Success (1 reporter), Mentor Externship (2 reporters), Alumni Engagement and Student Life (1 reporter), Holloran Center (2 reporters), Clinics (3 reporters), Career and Professional Development (3 reporters), Registrar (1 reporter), and Deans (5 reporters). St. Thomas Law does not currently have a Dean of Students.

By: Barbara Glesner Fines, Dean and Rubey M. Hulen Professor of Law, UMKC School of Law

During many Holloran Center Workshops since 2017, Jerry Organ (Co-Director of the Holloran Center) has asked participants to begin their exploration of professional identity formation with a simple question: “When did you first think of yourself as a lawyer?” Participants reflect on the question individually and then share their reflections. The question helps to highlight the development process that is identity formation and the key transitional moments in that process.

In a recent faculty workshop at my law school, we used that same exercise but with a slight variation. Participants were asked to think of an identity or a role that they have assumed as adults that is central to their concept of who they are. For many of us, parenthood is one such role, but we were encouraged to consider professional roles, including the one role we all had in common: “professor” or “teacher.” We were then asked to think back to one of the first times that we thought of ourselves as being or fitting into that role.

The identities shared varied widely: lawyer, teacher, mentor, public servant, military officer, and parent, among others. While the identities varied, the descriptions of the transformative moments that caused each of us to more fully assume that identity shared many characteristics.

Nearly all the incidents involved the awareness of significant responsibility for another. Whether it was the moment that a new parent brought their babies home from the hospital to the moment that a new attorney found strangers in a courthouse lobby asking for help, there was a realization that others were depending on us.

For many, the incidents had a sense of permanence as well—that the shift in our sense of self was not a momentary impression but a moment of transformation. This sense of movement might have been from outsider to insider, from observer to actor, or from one who follows to one who leads.

These moments often carried significant emotional weight as well. They were challenging, frightening, exhilarating, or confusing, but never mundane.

The process of reflecting on this question and sharing the reflections helped us to better understand the process of professional identity formation and to think more deeply about how we might guide our students along this path.

First, the exercise emphasized that, for most of us, transformative moments in professional identity formation came from an experience of acting in the role. That is not to say that formation never occurs in a classroom or in reading or listening, but transformative moments more often involve the emotional content that results from being given real responsibility to another. This realization led to a discussion of how we could provide or capture more of these high-impact experiences for our students.

Second, the exercise demonstrated the power of reflection as a pedagogy for identity formation. We saw that the process of reflection and discussion about identity and meaning were just as rigorous and had just as much impact as Socratic dialogue about the meaning of a legal doctrine. Not only did the exercise require reflection, but for many of us the transformative moments we were describing also included reflection as an integral component. “I remember thinking…” was a common phrase in the shared reflections. We discussed how we could more regularly incorporate reflection into our work with our students.

For faculty who are looking for helpful exercises to explore the meaning and practice of professional identity formation, this simple question accompanied by reflection can serve as an invaluable tool.

Please email me at bglesnerfines@umkc.edu if you have any questions or comments.

Barbara Glesner Fines is the Dean and Rubey M. Hulen Professor of Law at the University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Law.

By: Megan Bess, Director of the Externship Program and Assistant Professor of Law, University of Illinois Chicago School of Law

A few years ago, I set out to create my first externship course syllabus in my new role directing my school’s externship program. One of my goals to was to empower students to put their work in context and see how it fits in with the structure and goals of their externship organizations. I have found that without the coaxing to do so, students did not consistently seek out information about their organizations outside of the knowledge required to complete the work assigned by their supervising attorneys. Students are eager to make themselves useful to their immediate supervisors and colleagues. But an important opportunity for reflection that aids professional identity formation is missed without considering the larger context of how a student’s role and work contribute to the greater purpose of an organization and how that work serves and/or advances the legal profession.

As I was drafting the syllabus, a long-time adjunct showed me an assignment he developed for his government externship class. It prompted students to identify how decisions are made at the organization. At first glance, this seems simple enough to do. But there can be many layers to decision-making. This requires first identifying who the clients are. It also entails determining how decision-making is shared by clients and attorneys in the organization’s particular setting. He also asked students to describe any checks on the decision-making process. I immediately adapted a version of his reflective assignment for my externship section. I have tweaked it many times since then, but I remain impressed by the depth of investigation and reflection required for students to complete the assignment.

We have adjusted this slightly for students working in different settings. For example, when students extern with courts and/or judges, we ask them to identify the source of the court’s authority and the types of decisions made by the court or judge. We ask them to analyze the decision-making steps and any checks on decisions. When students extern for an organization’s in-house counsel, we help students reflect on how the goals of protecting the organization from liability and ensuring financial stability impact decision-making. Students with public interest organizations delve into decisions about the factors that determine which clients to take on and how to prioritize the use of organizational resources.

While this assignment was created for an externship setting, it has potential to aid in professional identity formation any time a law student works in a real-world legal setting. As part of their efforts to better incorporate professional identity formation, many schools have or are developing programs or guides to help prepare students for real-world lawyering experiences. These could include a suggestion that as part of a student’s onboarding, they investigate how decisions are made at the organization in which they will work. We can also help our students debrief and make sense of the work they have already done if we ask them these questions after they have engaged in a real-world legal experience.

To do this properly, students will need to understand the structure and mission of their organization and how attorneys support this mission. They will also need to identify the client or clients and which decisions attorneys can make and which are reserved for clients. I encourage students to identify examples to help illustrate this process and identify points of tension or confusion in the relationship between attorney and client. The process can be quite complicated, especially in large organizations. Such reflection requires students to think beyond their work and their role to understand the challenges inherent to the attorney’s role in the organization. In my experience, law students ultimately discover that the role of the attorney is not nearly as straightforward as it first seems. This firsthand knowledge of the challenges attorneys face is an invaluable part of their professional identity formation journey.

If you have questions or comments, please reach out to me at mbess@uic.edu.

Megan Bess is the Director of the Externship Program and Assistant Professor of Law at the University of Illinois Chicago School of Law.