By: Jabeen Adawi, Clinical Assistant Professor of Law, Director of the Family Law Clinic, University of Pittsburgh School of Law

In response to the American Bar Association (ABA) revised accreditation standard 303(b) requiring schools to provide “substantial opportunities to the students for… (3) the development of a professional identity,” law schools around the country began to remedy a perceived gap in legal education: the formal and intentional development of a cohesive professional identity. Unlike other client-serving professions—such as medicine or social work—law schools are often critiqued as not doing enough to explicitly support the development of a cohesive professional identity for lawyers. Legal education seemed to rely heavily on the existence of the model rules of conduct and one class in legal ethics to ensure that new lawyers understood their fiduciary responsibilities as lawyers. However, all along clinical pedagogy has been equipping clinical programs to move students through identity formation. Below, I’ll explain how at the University of Pittsburgh School of Law, the clinical faculty drew from well-developed tools and teaching approaches to synthesize a clinic-wide foundational orientation for clinic students that directly responds to standard 303(b).

The ABA standard states that professional identity is developed through an “intentional exploration of values, guiding principles, and well-being practices considered foundational to successful legal practice.” In analyzing the new standard, three distinct elements have emerged:

- Internalizing a deep responsibility and care orientation to others, especially the client,

- Developing ownership of continuous professional development towards excellence at the major competencies that clients, employers, and the legal system need, and

- Well-being practices.

The goal of our foundational orientation is to equip students with common skills and perspectives they will refine during their clinical experiences. Since this is our first pre-semester orientation, we are beginning with a half-day program of three sessions followed by a lunch and a small swearing-in ceremony. The skills we focus on meet the three elements of professional identity formation but are not exclusively the only ways we support student growth in our program.

Internalizing Deep Responsibility to Others

The first element promotes the fiduciary responsibilities of lawyers to their clients and society at large. It centers on developing and nurturing a mindset prioritizing a client’s interests above a lawyer’s self-interest. It also orients a law student to the profession’s commitment to pro bono services and developing a justice system that provides equal access and eliminates bias, discrimination, and racism.

To address the first element, our orientation begins with a session on “Understanding Your Responsibility Towards Clients and Society.” Clinic allows students to navigate the demands of real-life legal practice in a setting where clients are facing numerous odds in exercising their legal rights in the current system. However, I find that students need to be grounded in lived experiences of their clients first. For many of my clinical colleagues and me, a poverty simulation is one way to further perspective taking. This simulation will be followed up with discussion questions where students are reflecting upon the choices they were required to make, what circumstances influenced those choices, and what they may have done differently with a changed piece of their identity or additional resource.

The second step in orienting the students towards care of others requires a thoughtful discussion about one’s fiduciary responsibility as counsel. This can begin with a reflective exercise about a student’s own life where they look for experiences being in the care of another or taking care of someone else. These may be life experiences of seeking medical care, customer service, babysitting, caring for a sick relative, being a parent, or a prior career. Reflecting on their own life, a discussion can follow about lawyer’s specific responsibilities and how they relate to the fiduciary responsibility we take on for clients. This discussion will be grounded in the Pennsylvania Rules of Professional Conduct, specifically the preamble. This exercise should set the tone for their identity as lawyers who are in service of others.

I would be remiss if I didn’t acknowledge that a one-time conversation is not sufficient to develop care orientation. After the perspective-taking exercises are introduced in orientation, students will be equipped to revisit these ideas as they move through their clinic work. Typically, clinic students carry lower caseloads than in practice, so it affords them the ability to connect on a deeper level with a client and gain empathy and understanding for a client’s unique lived experience and their actual needs. During the year, individual supervision conversations can revisit the orientation discussions and further reinforce their care towards others.

By the end of the year, students are well equipped to engage in conversations critically assessing the legal system, identifying shortcomings, and proposing solutions. For example, many clinics end the year with a seminar dedicated to reflecting upon challenges their clients faced in accessing the courts, coupled with a brainstorming session on potential solutions.[1] This allows students to connect what may be frustrating realizations about “justice” to tangible solutions, thus beginning to develop their capacity to effectuate systemic change.

Developing Major Competencies

The second element includes making students aware of major competencies that clients, employers, and the legal system need. These competencies include client-centered relational skills, problem-solving, and good judgment. The goal is not only to make students aware of these competencies, and their importance, but also to internalize ownership of their own development in these areas.

The second session in our orientation introduces the students to one core competency: client-centered lawyering. Through a thoughtful exercise called “the Rich Aunt” students begin to consider how personal values drive human decision making and students begin to reframe the role of a lawyer from just an advocate to also that of a client-centered counselor.[2] This exercise has students consider a hypothetical scenario where they are lined up to receive a substantial inheritance but have to evaluate if they want to settle for a lower amount or go to trial and potentially obtain more. The students evaluate what factors drove them to their decision, and then reflect on how personal the decision was. This is then connected to choices a client may make and the value in respecting the client’s ability to decide.

After orientation, this client-centered perspective is reinforced during deeper seminars on counseling and interviewing skills. In future years, we intend to broaden the pre-semester orientation to also cover these topics so the foundation to these core competencies is uniformly reinforced across the clinical program. Finally, during the semester or year, students will deepen these skills within a clinical methodology that is structured to engage a student in learning the why behind their choices, reflecting upon their choices, and drawing strategies to implement in their legal practice. This is often done in a non-directive supervision model that is designed to maximize their opportunities for developing into a self-reflective practitioner.[3] This supervision model is not often available in traditional internship or externship positions.

Establishing Well-Being Practices

The final element of well-being practices goes beyond teaching self-care practices but instead looks at three core needs of the being: “(1) autonomy (to feel in control of one’s own goals and behavior); (2) competence (to feel one has the needed skills, including physical and mental skills to be successful); and (3) relatedness (to experience a sense of belonging or attachment to other people).”[4] Autonomy requires a student to understand their values, be able to express those values, and hence know where they are in control of their goals and behaviors. Hence, developing one’s sense of self as a person becomes foundational to developing the other necessary identities of a lawyer.

The pre-semester orientation will target this element in a third session focused on “maintaining well-being in a live-client setting.” In this session, we will examine the two elements that make up one’s professional quality of life: compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue. Then, we will introduce a tool called the “Professional Quality of Life Survey” that allows students to self-evaluate the different aspects that affect their quality of life. The Professional Quality of Life Survey is a free tool developed and refined through years of research on what affects a helper’s ability to continue their work. The Center for Victims of Torture owns the tool and provides it free (along with incredible teaching resources) to help anyone working in a helper-oriented profession.

While the results of the survey may be very private, students will not be required to share the results with anyone but can if they choose. I’ve found that the more ways we can provide students a space to discuss boundaries and personal challenges affecting their lawyering, we can assist them in developing skills to navigate issues that are inevitably going to arise in their lives. In private supervision, if a student chooses to share the results of the survey, together we can examine their trends and explore ways to improve their holistic satisfaction. The reality is that no one ever works in a vacuum: our personal lives and experiences come with us to our jobs and influence our work more than we often realize.

Hopefully, like us at Pitt Law, many other schools can utilize the revised ABA standards to bring attention to the strengths of their clinical programs. If anything, there is a wealth of information in clinical pedagogy—it just needs to be tapped.

If you have any questions or comments in response to this post, then please feel free to email at JZA16@pitt.edu.

Jabeen Adawi is Clinical Professor of Law and Director of the Family Law Clinic at the University of Pittsburgh School of Law.

[1] In “Teaching The Clinic Seminar” text by Deborah Epstein, Jane Aiken, and Wallace Mlyniec (three seminal clinical instructors from the Georgetown University Law Center), Chapter 21, “Exploring Justice” offers one thoughtful example of a framework for discussing justice in a clinical seminar. Another example is in Sue Bryant and Jean Koh Peters’ online repository for clinical law teaching materials “Talking about Race”, where they provide tools for facilitating conversations around racial justice.

[2] Deborah Epstein, Jane Aiken, Wallace Mlyniec, Teaching the Clinic Seminar 56 (2014) (describing the “Rich Aunt” exercise).

[3] See David Chavkin, Clinical Methodology in Clinical Legal Education: A Textbook for Law School Clinical Programs 7 (2002); Serge A. Martinez, Why are We Doing This? Cognitive Science and Nondirective Supervision in Clinical Teaching, 26 Kansas Journal of Law & Public Policy 24 (2016) (discussing the non-directive supervision model).

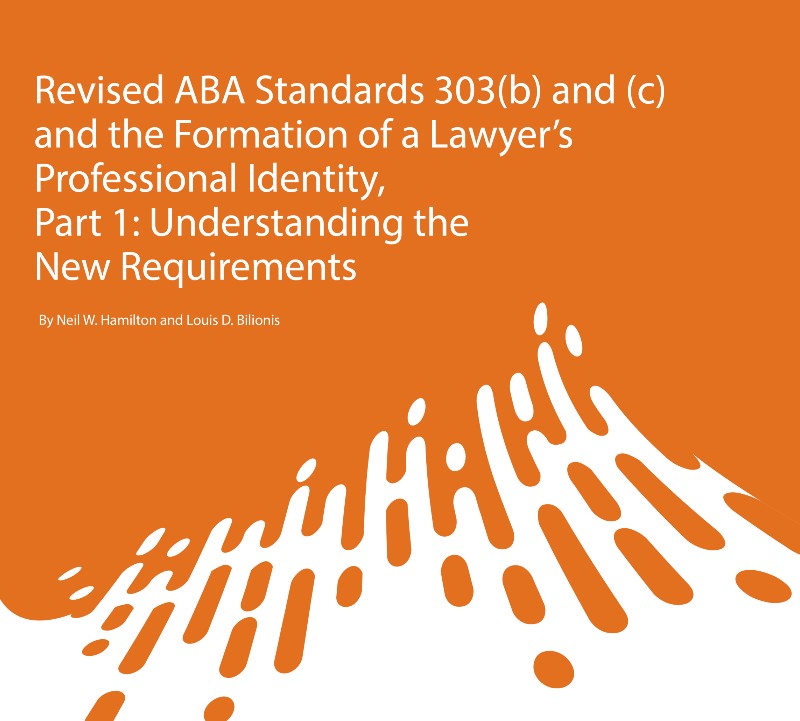

[4] Neil Hamilton, Louis Bilionis, Revised ABA Standards 303(b) and (c) and the Formation of a Lawyer’s Professional Identity, Part 1: Understanding the New Requirements (May 2022).

Third, self-doubt in law school, including imposter syndrome. This provided the foundation for Scott to discuss and demonstrate the power of mindfulness practices in law school. Scott shares a powerful image from his book

Third, self-doubt in law school, including imposter syndrome. This provided the foundation for Scott to discuss and demonstrate the power of mindfulness practices in law school. Scott shares a powerful image from his book