By: Jerry Organ, Bakken Professor of Law and Co-Director of the Holloran Center for Ethical Leadership in the Professions, University of St. Thomas School of Law

This blog posting updates my blog postings over the last several years regarding what we know about the transfer market, for example 2022, 2021 and 2020. With the ABA’s posting of the 2023 Standard 509 Reports, we now have a decade of more detailed transfer data from which to glean insights about the transfer market among law schools, which has been in decline for most of the last decade. This posting also includes a new section on transfer “feeder schools” and some reflections on whether and how law schools might be providing opportunities for professional identity formation for their transfer students.

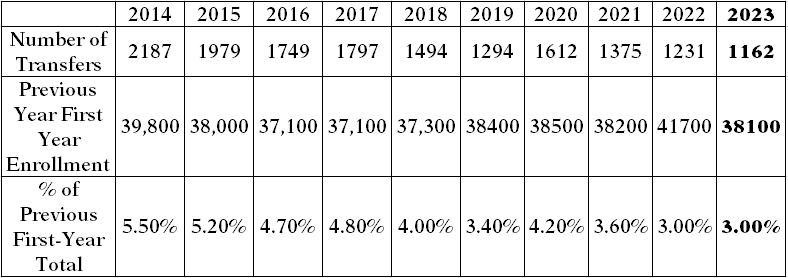

Numbers of Transfers and Percentage of Transfers Continue to Decline to the Lowest Levels in the Last Decade

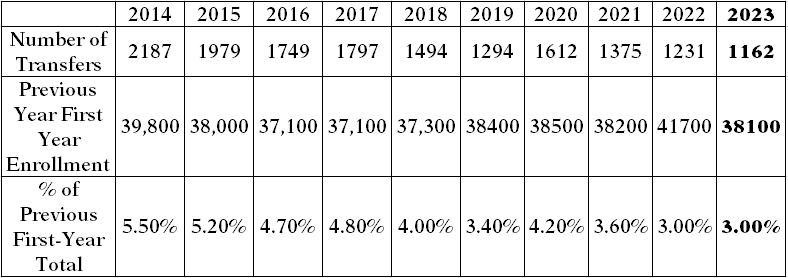

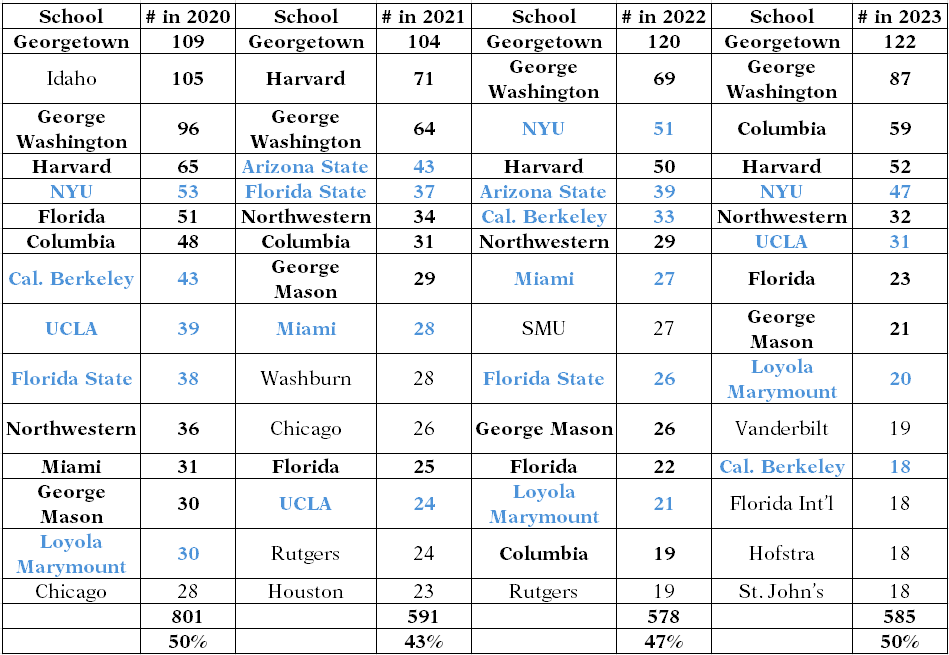

As shown in Table 1 below, the number of transfer students received by law schools in 2023 decreased for the third consecutive year to 1162, the smallest number of transfers in the last decade. For the last several years, the transfer market has been shrinking, having declined from 5.5% in 2014, to 4.7% in 2016, to 3.4% in 2019, to 3.0% in 2022 and again in 2023. Aside from a slight bump in 2017, and another bump in 2020, this drop reflects a continuation of a gradual decline in transfers over the last several years – from nearly 2200 to less than 1200 and from 5.5% of first-years in the previous fall to 3.0% (both down over 45%).

Table 1 – Number of Transfers and Percentage of Transfers from 2014-2023

After an increase in transfers in 2020, we have seen declines in 2021 to 1375 and 3.6%, 2022 to 1231 and 3.0%, and 2023 to 1162 and 3.0% – the lowest number and percentage in a decade.

My sense is that the dramatic increase in scholarship assistance over the last decade, including the elimination of conditional scholarships at dozens of law schools, has made the financial equation associated with transferring much less attractive. (The number of law schools with conditional scholarship programs dropped from roughly 140 in 2011 to fewer than 80 as of 2020.) If a student were going to be paying full tuition at a given law school and could transfer to a much higher ranked law school in the region for only marginal additional cost (and perhaps without having to move), transferring might make sense. But if a student has to forego scholarship assistance and absorb significantly more financial cost to transfer, then staying at the student’s initial law school might seem to make more sense.

SOME LAW SCHOOLS CONTINUE TO DOMINATE THE TRANSFER MARKET

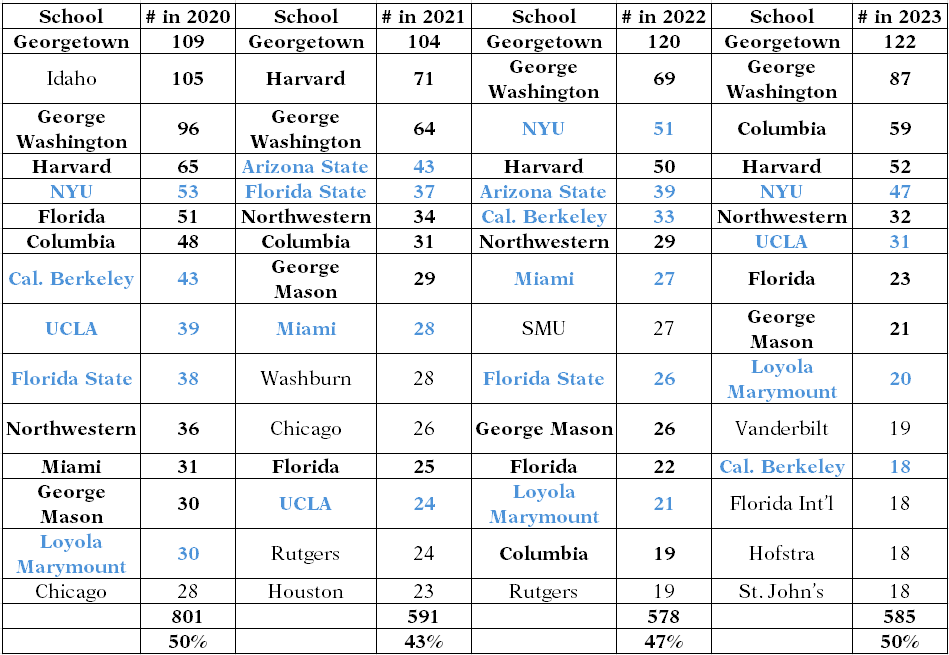

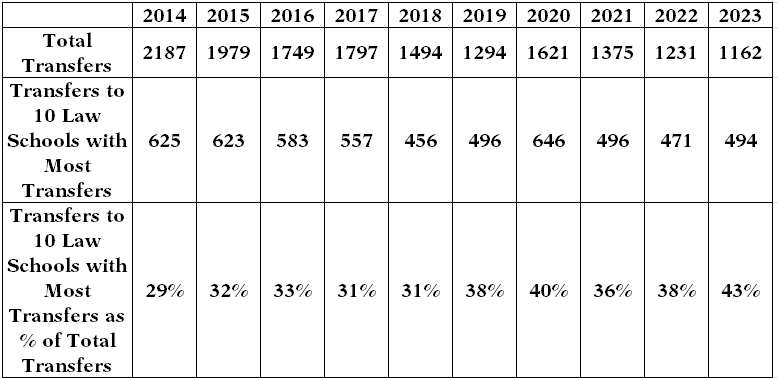

Table 2 below lists the top 15 law schools participating in the transfer market in descending order in Summer 2020 (fall 2019 entering class), Summer 2021 (fall 2020 entering class), Summer 2022 (fall 2021 entering class), and Summer 2023 (fall 2022 entering class).

(Note that in Table 2 and in Table 4, the “repeat players” are bolded – those schools in the top 15 for all four years are in black, those schools in the top 15 for three of the four years are in blue.) Seven of the top 15 for 2023 have been on the list for the largest number of transfers all four years, with four having been on the list for three of the four years (including 2023). Florida dropped out of the top 15 this year after having been in the top 15 the prior four years, while Florida State and Miami dropped out of the top 15 this year after having been in the top 15 the prior three years. There are four newcomers to the list in 2023: Vanderbilt, Florida International, Hofstra, and St. John’s. Table 2 also shows that for 2023, the concentration of transfers in the top 15 law schools for transfers increased back to 50%, where it was in 2020, up from 43% in 2021 and 47% in 2022.

TABLE 2 — Largest Law Schools by Number of Transfers from 2020-2023

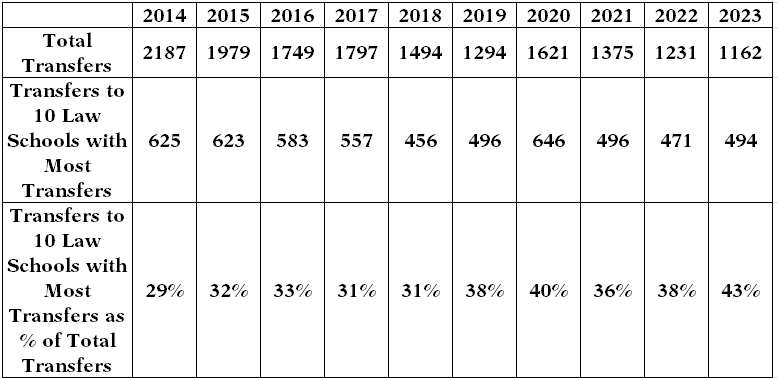

As shown in Table 3 below, if we focus just on the top ten law schools for transfers in, the total number of transfers is 494 – 43% of all transfers – the highest percentage in the last decade.

TABLE 3 – Totals for Top Ten Law Schools for Transfers In as a Percentage of All Transfers for 2014-2023

In terms of law schools with the highest percentage of transfers in as a percentage of their previous year’s first-year class, as shown below in Table 4, eight law schools have been on the list each of the last four years – Chicago, Florida, Florida State, George Mason, Georgetown, George Washington, Northwestern and UNLV. Four law schools have been on the list three times in the last four years – Florida Int’l, Harvard, NYU, and Vanderbilt (including 2023). Two of the other three schools have been on the list in two of the last four years (including 2023) – Columbia and UCLA. The number of law schools welcoming transfers representing 20% or more of their first-year class has fallen from nine in 2013 (not shown), to none in 2019, four in 2020, two in 2021, and only one in 2022 and 2023 (Georgetown in both years).

TABLE 4 — Largest Law Schools by Transfers as a Percentage of Previous First-Year Class – 2020-2023

TRANSFER FEEDER SCHOOLS

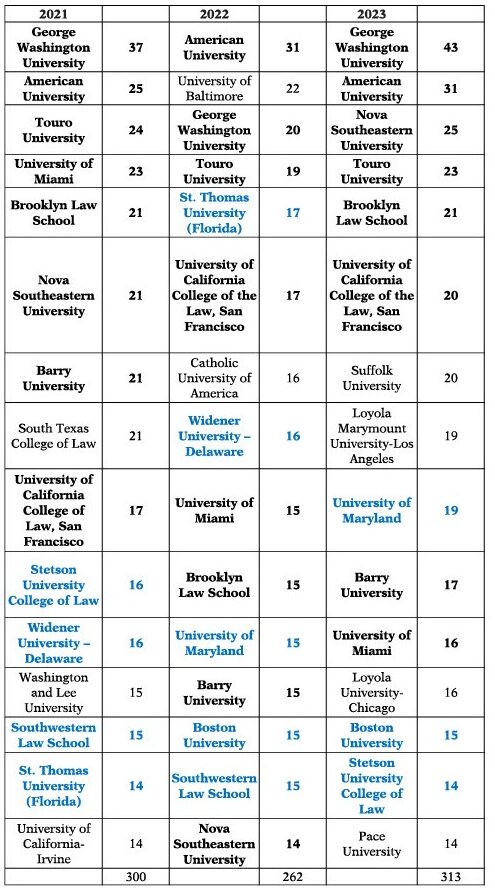

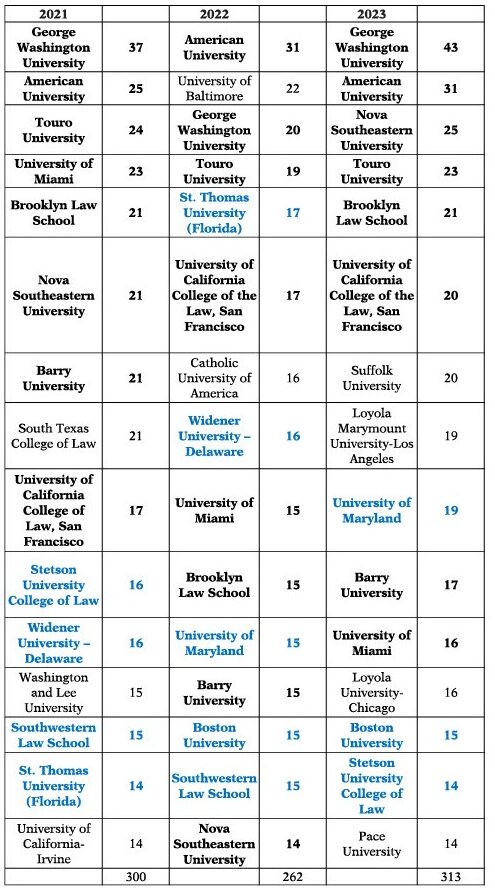

There also are some law schools that appear consistently in the list of top feeder schools for transfers as shown below in Table 5. These fifteen schools have been responsible for roughly 25-30% of transfer students in each of the last three years.

TABLE 5 — Largest Law Schools by Transfers Out for 2021-2023

Eight law schools have been on the list of top transfer out law schools in each of the last three years – American, Barry University, Brooklyn Law School, George Washington University, Nova Southeastern, Touro University, University of California College of the Law, San Francisco, and the University of Miami. There are three additional law schools on the list in two of the last three years (including 2023): Boston University, Stetson University College of Law, and University of Maryland. In addition, there are three schools that made the list of the top-15 law schools for transfers out in both 2021 and 2022, but not in 2023: Southwestern University, St. Thomas University (Florida), and Widener University-Delaware.

Notably, two of these schools – George Washington University and Miami — show up on both the transfer out in Table 5 and the transfer in list above in Table 2. They are losing students to higher-ranked law schools and then back-filling with their own transfers from lower-ranked schools.

NATIONAL AND REGIONAL MARKETS –

Starting in December 2014, the ABA Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar began collecting and requiring law schools with 12 or more transfers in to report not only the number of students who have transferred in, but also the law schools from which they came (indicating the number from each law school). In addition, the law schools with 12 or more transfers in had to report the 75%, 50% and 25% first-year, law school GPAs of the students who transferred in. This allows one to look at where students are coming from and are going to, as well as the first-year GPA profile of students transferring in to different law schools.

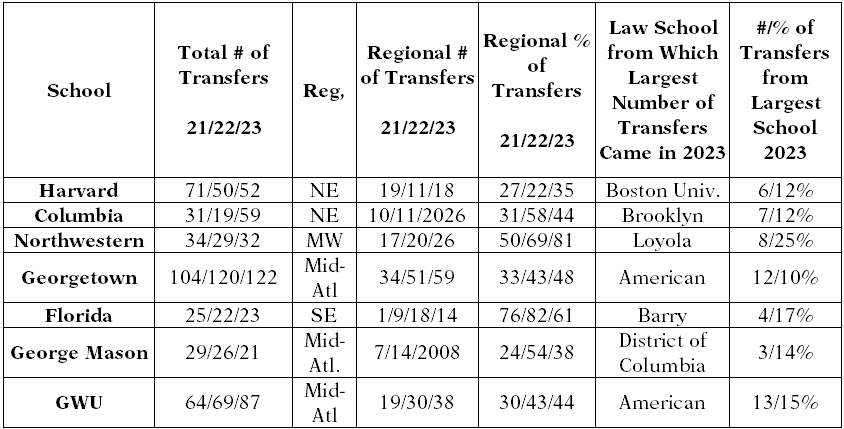

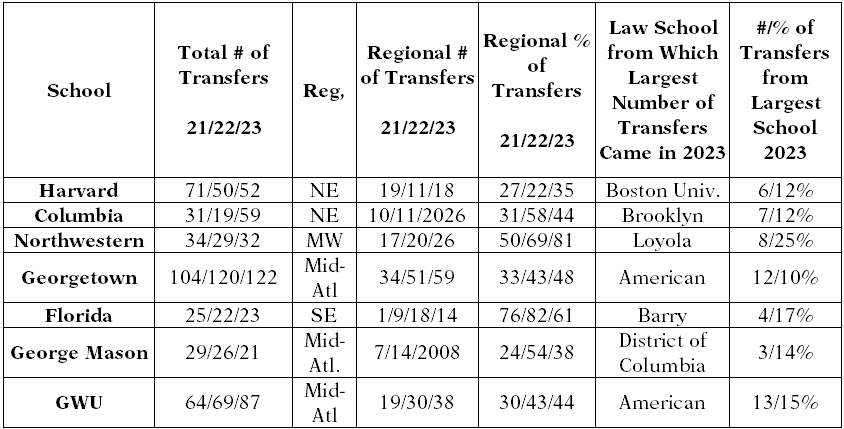

Table 6 below focuses on the seven law schools in Table 2 that have been among the top-15 in terms of number of transfers in for each of the last four years, presented in descending U.S. News & World Report (U.S. News) rank. Table 6 indicates the extent to which these seven law schools were attracting transfers from the geographic region in which they are located and highlights that the transfer market, to some extent, is a set of regional sub-markets.

TABLE 6 — Percentage of Transfers from Within Geographic Region 2021-2022-2023 and Top Feeder School for 2023 at the Seven Law Schools among the Top-15 for Transfers In for 2021, 2021, and 2023

All seven law schools had at least 35% of their transfers from the region in which they are located. Two of these seven law schools, Northwestern and Florida, obtained most of their transfers from within the geographic region within which the law school is located for the last three years, (with 80% for Northwestern and 60% for Florida in 2023). On the other hand, three law schools (Harvard and Georgetown and George Washington) had 48% or fewer of their transfers from within the region in which the law school is located in each of the last three years.

When one looks at the transfer out schools in Table 5 in comparison with the transfer in schools in Table 2, one can see some of the regional realities. In Florida, Barry University, Miami, Nova Southeastern, St. Thomas University, and Stetson are transfer feeder schools with Florida, Florida International, Florida State, and Miami receiving a number of those transfers. In the Mid-Atlantic, American, Baltimore, Catholic, George Washington University, and Maryland are transfer feeder schools with George Mason, Georgetown, and George Washington receiving a number of transfers. In California, Loyola Marymount, Southwestern, and the University of California College of Law San Francisco are transfer feeder schools with Loyola Marymount, University of California Berkeley, and University of California Los Angeles receiving a number of transfers.

Table 6 also identifies the law school that provided the largest number of transfers to each listed law school in 2023, as well as the percentage of transfers that came from that school. One of the seven law schools had a significant percentage (more than 20%) of its transfers in from one feeder school – Northwestern – with 25% of its transfers coming from Loyola-Chicago (and over 65% from Loyola/DePaul/UIC).

Notably, six of these seven law schools that are consistent players in the transfer market are on the East Coast (Harvard, Columbia, Florida, George Mason, Georgetown, and George Washington) while one is in the Midwest (Northwestern).

VARIED QUALITY OF THE TRANSFER POOL

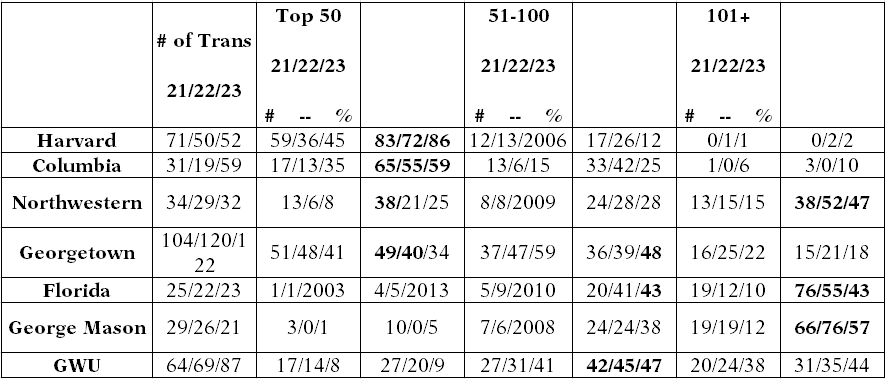

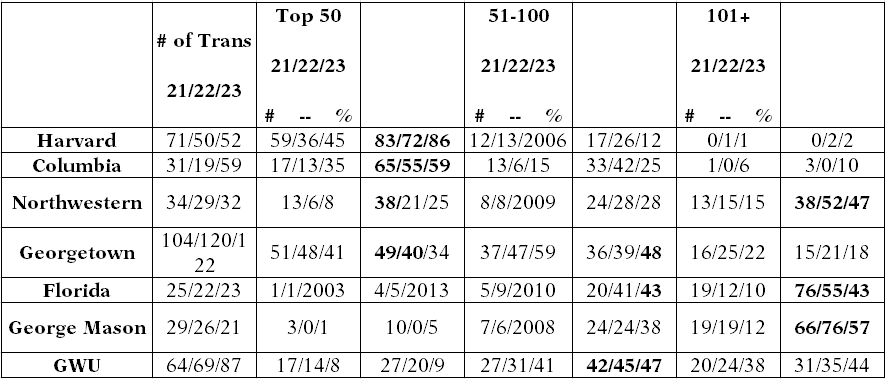

Table 7 below shows the tiers of law schools from which these seven largest law schools in the transfer market for each of the last four years received their transfer students. Four of the seven law schools that consistently have high numbers of transfers in are ranked in the top 15 in U.S. News, while the other three are ranked between 28 (Florida and George Mason) and 41 (George Washington).

TABLE 7 — Percentage of Transfers from Different Tiers of School(s) for 2021, 2022 and 2023 at the Seven Law Schools Among the Top-15 for Transfers in 2021, 2022, and 2023

Two of the seven law schools – Harvard (no lower than 72%) and Columbia (no lower than 55%) — have consistently had large percentages of their transfers from law schools ranked between 1 and 50 in the U.S. News rankings. By contrast, in 2023, four of these seven law schools had more than 40% of their transfers from law schools ranked 101 or lower (Florida, George Mason, George Washington, and Northwestern).

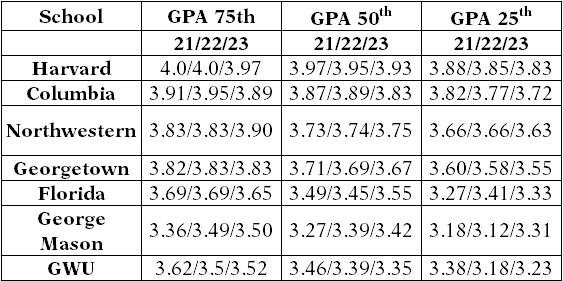

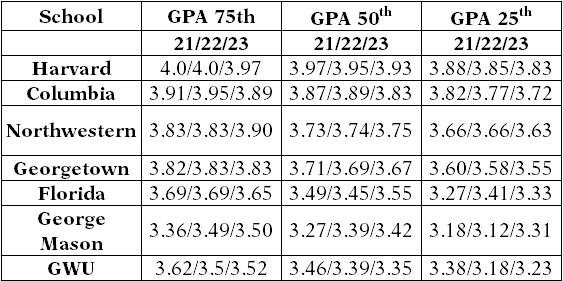

TABLE 8 — First-Year Law School 75th/50th/25th GPA of Transfers in 2021, 2022, and 2023 at the Seven Law Schools among the Top-15 for Transfers in 2021, 2022, and 2023

Table 8 above highlights the reported GPAs of transfers in for these seven law schools. In looking at Table 8, one quickly sees that of the four law schools ranked in the U.S. News top-15, only one – Harvard — has a 50th GPA for transfers in 2023 that is above 3.9, and a 25th GPA of 3.8 and above. Harvard also is accepting most of its transfers in from top-50 law schools, making it clear that it is accepting transfers in who could have been admitted to Harvard in the first instance. Columbia is a close second, with all three of its metrics close to 0.1 below those of Harvard.

The other two top-15 law schools – Northwestern and Georgetown – are a step below in terms of the credentials of their transfers, with 50th GPAs of 3.75 and 3.67, respectively, and with 25th GPAs of 3.63 and 3.55, respectively, in 2023. In 2023, more than 65% of Georgetown’s transfers were from law schools ranked 51 or lower while 75% of Northwestern’s transfers were from law schools ranked 51 or lower. For Georgetown and Northwestern, with a majority of their transfers coming from law schools ranked outside the top 50, many of these transfer students may not have had the credentials to be admitted as first-year students at Georgetown or Northwestern.

Once you drop out of the top-15, the other three law schools – Florida (3.55), George Mason (3.42), and George Washington (3.35) – each has a 50th GPA well below that of the other four law schools on the list and 25th GPAs that drop to 3.33, 3.31, and 3.23, respectively. With 85% or more of these transfers coming from law schools ranked 51 or lower, these law schools clearly are welcoming a number of transfer students whose entering credentials almost certainly were sufficiently distinct from each of those law schools’ entering class credentials that the transfer students they are admitting would not have been admitted as first-year students in the prior year.

STILL MANY UNKNOWNS

As I have noted for the last few years, these more detailed transfer data from the ABA should be very helpful to prospective law students and pre-law advisors, and to current law students who are considering transferring. These data give them a better idea of what transfer opportunities might be available depending upon where they are planning to go to law school (or are presently enrolled as a first-year student).

Even with this more granular data now available, however, there still are a significant number of unknowns relating to transfer students, particularly regarding gender and ethnicity of transfer students and performance of transfer students at their new law school (both academically and in terms of bar passage and employment).

With the increased emphasis on professional identity formation reflected in ABA Standard 303(b)(3) and (c), there may be questions about how law schools are addressing professional identity formation for transfer students, particularly at those law schools that have added a first-year course/program focused on professional development or professional identity formation.

Are these law schools requiring transfers to take these courses with their incoming first-year students? Are there specific professional development or professional identity formation courses structured for transfer students at those law schools with a significant cohort of transfer students (10-15 or more)? Are there better ways to address the professional identity formation of transfer students that would help them integrate into the law school community into which they are transferring? These are questions for which additional research would be warranted.

Please feel free to contact me at jmorgan@stthomas.edu should you have any comments or questions.

Jerome Organ is the Bakken Professor of Law and Co-Director of the Holloran Center for Ethical Leadership in the Professions at the University of St. Thomas School of Law