By: Michael Robak, Director of the Schoenecker Law Library, Associate Dean, and Clinical Professor, University of St. Thomas School of Law

The concept behind developing a robust advising management application is to create “One File” of information developed by and about each student from the law school’s whole organization as the student moves through their law school career.

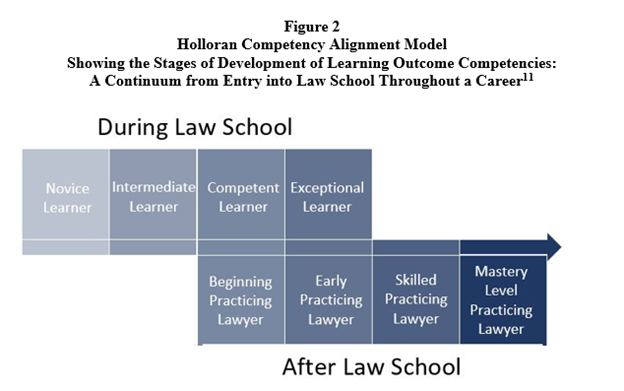

Collecting uniform information in one place, and allowing for appropriate organization-wide access will, we believe, create an advising mechanism that helps each law student move from novice to professional as described in the Holloran Center’s Competency Alignment Model. (Figure 2 below)

This information system is comprised of three elements:

The first element of this platform, Coordinated Coaching, will be used to capture information for each student from the nine coaching touch points that occur in their journey through law school as identified by Professors and Co-Directors of the Holloran Center Neil Hamilton and Jerry Organ. The Coordinated Coaching takes place at several points: (1) 1L Fall in a mandatory meeting with the Office of Career and Professional Development (CPD), which is described below in detail; (2) 1L Spring in a mandatory 1L class, Serving Clients Well, where professors, alumni, and local attorneys serve as coaches to the law students who work through Neil Hamilton’s award-winning Roadmap book regarding a student’s journey to finding meaningful employment; and (3) 2L and 3L years in the mandatory Mentor Externship program in which the professors teaching the classroom component of this program continue coaching and guiding the students. Capturing information from all of these contributors at these different times will allow for those coaching the students to coordinate to better assist student development of learning outcome competencies. Currently this information is captured and stored in multiple systems and trapped in organizational silos.

The second element of this platform is the Academic Communication System (ACS). We know, anecdotally, there are behavioral “red flags” which constitute potential clues (data points) for those at risk. The University of St. Thomas School of Law (“School of Law”) currently has nothing in place to serve as a tracking/communication platform for all the department administrators to record and share these interactions—the ACS would serve that function. The backbone of this element is key information for all students brought in from Banner. There are eight School of Law departments that would provide information into the system through twenty-three “Reporters” from across those organizations. [1] The first and most important interactions to capture are the ones with the Director of Academic Achievement and Bar Success as the Director is usually the first stop for students who have some academic success issues or concerns.

The third element of the platform, the Self-Directed Index, allows us to identify the students most at risk for possible problems with first-time bar passage and employment outcomes. While there is anecdotal evidence suggesting about 20% of students in any given year are at risk, we are seeking to fine tune that identification by developing an instrument to gauge an individual student’s self-directedness. This self-directed index would pull information primarily from Canvas. For example, one item of potential concern is class attendance. With the use of the Canvas attendance tracker, we could gather student information for each semester looking for patterns of activity. Another example includes tracking when students turn in their assignments? Are assignments submitted by students early, on time, or late? This is another variable we would be able to examine.

With these three platform elements in place, the One File system becomes the single source for capturing all the information about the student journey.

The Applications behind One File are Salesforce, Qualtrics, and Canvas. Salesforce will be customized for this specific project. Qualtrics will be used to capture the Coordinated Coaching and Academic Communication System information. The Self-Directed index will primarily rely on Canvas data.

Phase One of the One File system is putting parts of the Coordinated Coaching and Academic Communication System in place by the end of the Spring 2023 semester. For the Coordinated Coaching element, One File is “starting from scratch” with only the current 1L class; we are investing in the Class of 2025 as our beta group. We are not seeking to make One File retrospective for Coordinated Coaching.

At launch it will be built to hold the information for that Class’s 1L and 2L years. We would seek to add the 3L year sometime later in 2023 or early 2024. We have identified nine coaching touch points through the student’s law school journey for which we wish to track key information, and this first phase will track the first five touch points occurring in the 1L and 2L years. The last four touch points occur during the 3L year and are similar to the 2L year with the addition of a CPD exit interview and work for bar preparation through the JD Compass program.

Phase one development of the Academic Communication System will be built for our Director of Academic Success to capture the interactions with students. We anticipate broadening this to include other “Reporters” who can provide additional information to the file.

COORDINATED COACHING – the Beginning Touch Points

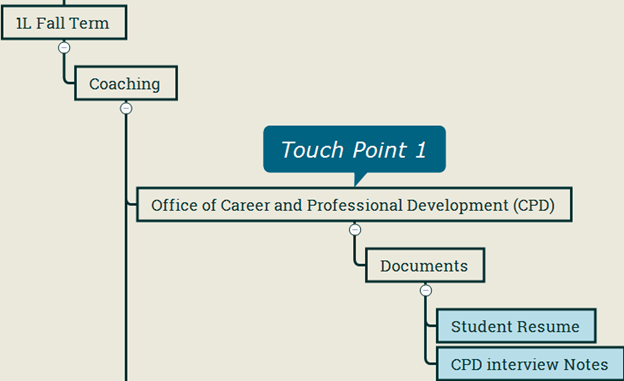

The first Coordinated Coaching touch point occurs during the 1L Fall term. Each 1L meets with a CPD team member, and this provides the initial (and base line) information about the student.

Coaching Touch Point 1:

Currently, CPD uses Symplicity for storing student resumes, as well as their meeting notes with students. In addition to the resume, the data we will capture in Salesforce for this touch point are:

CPD Meeting in First Year

- Practice Areas of Interest

- Geography of Interest

- Quick Assessment of Self-Directedness

These questions will be captured using a Qualtrics survey. The first two questions are answered by the students on their own or as part of the CPD meeting. The third question would need to be answered by CPD. We created a drop-down menu for the Practice Areas and Geography to create uniformity and consistency in the data gathered.

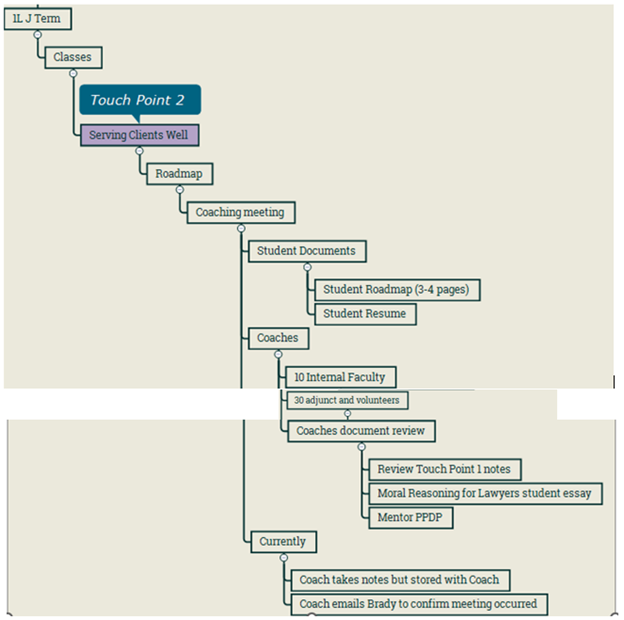

Coaching Touch Point 2: The second touch point, the Roadmap Coaching meeting, occurs early in the spring semester of the 1L year in conjunction with the Serving Clients Well class.

Prior to meeting with their Coach, the students create a student Roadmap and upload it to Canvas. The coaches have not had a single place to store the information they keep on their Coaching meetings with the students. In addition, two other documents have been created by the students, an essay written for the Moral Reasoning for Lawyers course and a Personal and Professional Development Plan written for the Mentor program. These documents, along with the completed student Roadmap template, will be placed in Salesforce and made available for review.

Qualtrics will be used for capturing the following data:

- Practice Areas of Interest

- Type of employer

- Geography of Interest

- Students self-identified and peer-affirmed strengths/competencies

- Quick Assessment of whether student understands concept of having to communicate a persuasive story of value and has good stories to tell

- Quick Assessment of Self-Directedness

- Identified goals for summer

- Identified interests for registration for next year

- Identified possible Mentor Experiences in which student is interested in next year

Again, we will be using drop downs to create uniform data capture.

This is a high-level overview of the One File system. Also, somewhat unique in the development of the application, we are not building the system all at one time. As mentioned earlier, we are starting with the School of Law Class of 2025 as the beginning point. We will be developing the system as that class moves through its law school career and then add the following incoming classes. In this way we can also learn as we develop the platform and allow for continuous improvement. We’ll have more to describe as we continue this journey.

If you have questions or comments, please reach out to me at michaelrobak@stthomas.edu.

Michael Robak is the Director of the Schoenecker Law Library, Associate Dean, and Clinical Professor at the University of St. Thomas School of Law.

[1] The Departments and Reporter count are as follows: Lawyering Skills (5 reporters), Academic Achievement and Bar Success (1 reporter), Mentor Externship (2 reporters), Alumni Engagement and Student Life (1 reporter), Holloran Center (2 reporters), Clinics (3 reporters), Career and Professional Development (3 reporters), Registrar (1 reporter), and Deans (5 reporters). St. Thomas Law does not currently have a Dean of Students.