This past spring of 2013, I taught a graduate seminar on the history of the built environment in New Orleans. The class was a natural progression from my own research on Frank Gehry and his domestic work, as tenants have recently moved into a Gehry-designed duplex in Brad Pitt’s Make it Right Foundation in the Lower Ninth Ward, an area decimated by the wall break in the Industrial Canal at the time of Hurricane Katrina. I realized last fall, however, that student interest in going to New Orleans was great when I was conducting advising sessions (in my role as Director of Graduate Studies) so I decided to put some things together for those wanting to make the trip. Students paid their own way to NOLA and spent time during the early part of spring break week researching their own projects. The latter portion of the week was spent in group activities. The Art History Department supported this trip by funding a five-hour long bus tour of the Lower Ninth Ward homes led by the Make it Right Foundation’s executive architect, John Williams, a long time New Orleans designer. I also arranged a walking tour for students to lead, a visit with a local preservationist, as well as a tour of a local cemetery. Here’s a look at our experiences as seen through the eyes of three of the students on the trip!

Victoria Young

NOLA trip group photo in front of New Orleans Cathedral

On the Ground in New Orleans: Architectural Walking Tour By Ava Grosskopf

The first class gathering of the trip was a walking tour of New Orleans. The tour took nearly four hours and spanned the French Quarter, the Mississippi riverfront and the Central Business and Warehouse Districts. We began at the famed Café du Monde and ended at the World War II Museum. Each of the nine students on the trip was assigned a specific building or public space to research and share their knowledge with the class in a brief five-minute presentation on site.

Dr. Young presented us with a challenge to do the research of the location we were assigned but not to visit the location beforehand., so that we would incorporate into our five minute presentation our reaction to the site upon seeing it for the first time. The most common effect to this directive was that many of us found ourselves reacting to how much smaller a building was than we expected. It seems that New Orleanians have become very adept at making small spaces look much larger than any photo depicted. As a result, the city holds an immense amount of American history in only the few square miles we covered on the tour.

A number of the other buildings intrigued us on the walk, particularly those we had studied in class. The discussions about these structures were enjoyable and interesting. Although the walking tour was not directly related to my research topic, Planter’s Grove, it did provide exposure for the class as to how the landscape of New Orleans is laid out, and how the residents interact within it.

Students at Piazza d’Italia.

Make it Right: Touring the Lower Ninth Ward By Soren Hoeger-Lerdal

During registration for spring 2013 courses, the prospect of a New Orleans spring break vacation to supplement our NOLA architectural history class was exciting, to say the least. When, in the spring, Dr. Victoria Young announced that the Department had won, via auction, a bus tour of the Lower Ninth Ward, an unparalleled adventure was added to an already crowded itinerary.

So when the Friday morning of our tour arrived, we began our venture at the offices of Architect John Williams, the principal architect of the Make It Right project and master planner of the entire Lower Ninth Ward. After a short but exceptionally informative and eye-opening presentation, accompanied by incredible images, we got on a bus donated by Tulane University. John first took us to the Global Green Homes, a LEED Platinum development focused on sustainability, replicability and affordability. Next, he took us to meet and pick up J.F. “Smitty” Smith, a slightly less than optimistic Lower Ninth Ward resident, who at times commandeered, to our delight, both the talking aspect of our tour as well as the very cooperative bus driver’s route (it was Good Friday, her day off, after all). In fact, one of the most eye opening and memorable aspects of the tour was an impromptu detour to Chalmette in St Bernard Parish, neighbor to the east of the Lower Ninth. Smitty called this area “Bush’s Children” due to former President Bush’s lobbying for the area’s recovery. The parish is near complete restoration and evidence of the hurricane was nowhere evident.

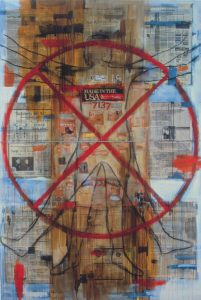

We then returned to the Lower Ninth and visited the House of Dance and Feathers, a museum-shed created by Ronnie Lewis preserving the history of Mardi Gras Indians and Lower Ninth residents. His vibrant optimism stands in direct opposition to Smitty’s, yet they have mutual goals and such stunning determination. Another shocking aspect of our tour was John explaining visually the actual lot sizes in the Lower Ninth Ward. At just 30 feet wide, the extent of the pure destruction can only be grasped on the site. Blocks, which were previously lined with wall-to-wall homes, are now lucky to have two occupied buildings; many blocks have none. Brick staircases that lead to nowhere, overgrown lots of grass and weeds, and still shuttered homes marked with the infamous “X” of the first-responders still dominate the landscape. John explained the significance of the numbers located in each quadrant of the spray painted “X”. Although number of dead was the bottom number, I think the most shocking to us all was the number located at the top signifying the date that the home was first checked. We were all left in disbelief to see many of the Lower Ninth Ward homes were not entered until nearly a month after the storm, some as late as October.

Our next stop was to meet “Johnnie” at the Bayou Bienvenue. John Taylor (everybody has a fun nickname it seemed) is the guardian of a platform that sits between his native Lower Ninth and his true home, the bayou. John told us stories about his childhood, when the now scattered baldcypress stumps were a full-grown forest in the freshwater bayou. He would spend days away from home at the bayou until his brother would be sent as a lone search committee.

Finally, we ended at the Make It Right project and no, there was no Brad Pitt sighting. After a brief history and walking tour, we were surprised and honored when John allowed us to tour an under construction home. This was especially special considering the first non-residents were allowed to tour the homes only three months prior. This was not due to secrecy, John said, they simply did not want to waste any time getting people back home. Although a few of us questioned the aesthetic longevity of the extremely modern style of the homes, the sustainability and green focused collection of homes is absolutely unprecedented and will unquestionably serve as a precedent for future neighborhood design. Simply stated, this was a dream tour.

This photo, taken by graduate student Lauren Greer, shows the new construction of the spot where the levees broke, flooding the Lower Ninth Ward. An attempt is being made to Landmark the spot, peculiar both for the timeframe (far too recent) and construction type (it is a concrete wall, after all).

The tour group with John Williams (center) standing in front of the Frank Gehry- designed Lower Ninth Ward residence. Photo by author.

While snapping this photo, Smitty smirked while asking me “Do you get it?” Of course it signifies that FEMA is in the doghouse for all Lower Ninth Residents. A visual defiance of the way the government handled their neighborhood. Photo by author.

Cemeteries on Paper and In Person: Lafayette Cemetery #1 By Sandy Tomney

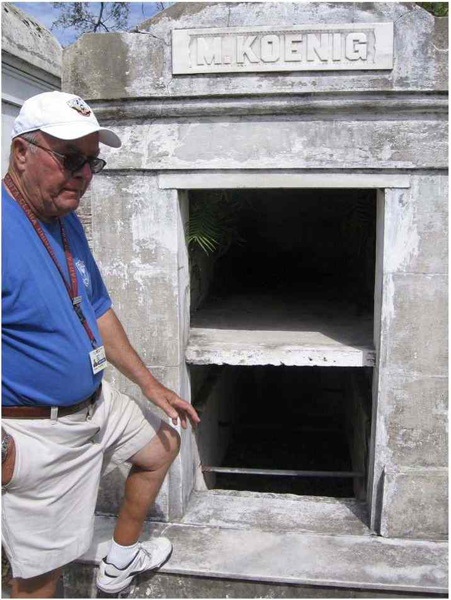

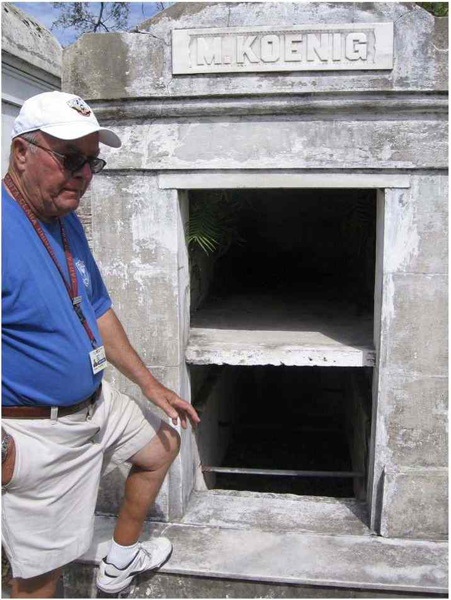

New Orleans has much to discover. Our trip included an itinerary of an architectural walking tour, a tour of the lower ninth ward, a meeting with a preservationist, and a tour of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. All of the activities were based on concepts and themes we have been studying in class and each was interesting. Since the research I am conducting concerns the Garden District’s Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 during the antebellum years, this trip was a great opportunity. It gave me a chance to become more familiar with how the cemetery fits into its context. Doing site visits at both St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 and Lafayette also made it possible to compare two similar sites located in different parts of the city. Our tour guide at Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 was affiliated with the organization Save Our Cemeteries. He pointed out the four basic above ground interment types in the cemetery – wall vault, family, and society tombs, as well as the coping style grave. He also explained how the family tombs functioned. Another highlight was the explanation as to why family tombs were often found in groups of four. Contractors and/or speculators would buy cemetery lots in groups of four, erect family tombs on them, and resell them as needed. This helped to answer a question I had concerning the relationship between similar tomb styles located within the cemetery and the ethnicity of the families interred in them. Since our guide is a resident of the neighborhood next to Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, he ended our outing with a walking tour of the upscale area adjacent to the cemetery, with homes of John Goodman and Sandra Bullock among others.

Save Our Cemeteries guide Val Connolly explains how family tombs function. Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, New Orleans, LA, 2013. Photo: Sandy Tomney

Wall Vaults. Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, New Orleans, LA, 2013. Photo: Sandy Tomney

Family Tombs. Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, New Orleans, LA, 2013. Photo: Sandy Tomney

Henry Dick Tomb. Probably designed by J.N.B. DePouilly. Italian Marble. St. Louis Cemetery #1, New Orleans, LA, 2013. Photo: Sandy Tomney

Henry Dick Tomb. Probably designed by J.N.B. DePouilly. Italian Marble. St. Louis Cemetery #1, New Orleans, LA, 2013. Photo: Sandy Tomney