Michelle Turner is a graduate student in the Master of Arts in Art History and Graduate Certificate in Museum Studies program. Michelle was awarded a Department of Art History Student Research Grant to support her Qualifying Paper research.

A screen-shot of the temperature differences between the locations on my trip and Minneapolis, which was experiencing the 2019 Polar Vortex.

This January, right as the 2019 winter vortex hit, the University of St. Thomas provided me the opportunity to leave. Thanks to the Department of Art History Student Research Grant, I was able to travel to England and develop my Qualifying Paper abroad. My paper focuses on British artist Sonia Boyce and her ongoing relationship with wallpaper throughout the span of her career. Many scholars and critics either focus on the conceptual similarities across Boyce’s oeuvre or they silo her work into two camps: her drawings pre-1990 and her collaborative work post-1990. My paper aims to bridge Boyce’s art practice by also attending to the aesthetic.

I was first introduced to the work of Sonia Boyce by Dr. Heather Shirey in her spring 2018 seminar “Afropean: Africa and Europe.” Boyce was suggested to me by Dr. Shirey as a possible research subject. My paper began by exploring Boyce’s visual commentary on Britain’s race relations. Her work was intended to be one case study among a collection of others that highlighted the disparity between ideas of diversity and inclusion. Yet, as I began to survey the breadth of Boyce’s work, in particular, her collaborative and often performative pieces post-1990, I became fascinated by her new use of wallpaper. In her pre-1990 drawings, wallpaper was used as a regular backdrop behind her figures, but in her later work, Boyce took wallpaper off the canvas and gave it new dimensions, the ability to engulf and alter the space we inhabit.

A photo with Sonia Boyce.

Nervous that at any point I would step upon a source which had undoubtedly already written on this topic, I both voraciously surveyed whatever records and writings I could find and proceeded with caution. With less than ten days before our final class presentations, I emailed Dr. Shirey my intention to switch my paper’s focus. I was met with “you are in the trenches with the research, and you’ll be the best judge as to what is possible at this point in the research/semester.” I took that as a go.

Ultimately the topic was well received and turned into my Qualifying Paper. Over the summer, I reached out to Boyce directly and in the fall, I applied for the Department of Art History Student Research Grant. My time abroad allowed me the opportunity to see many of Boyce’s work in person, hold conversations with a number of art professionals who had worked directly with Boyce and/or her work, as well as meet and interview Sonia Boyce.

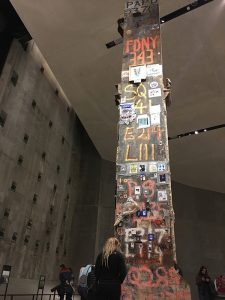

Me in front of Boyce’s 1986 drawing Lay back, keep quiet and think of what made Britain so great.

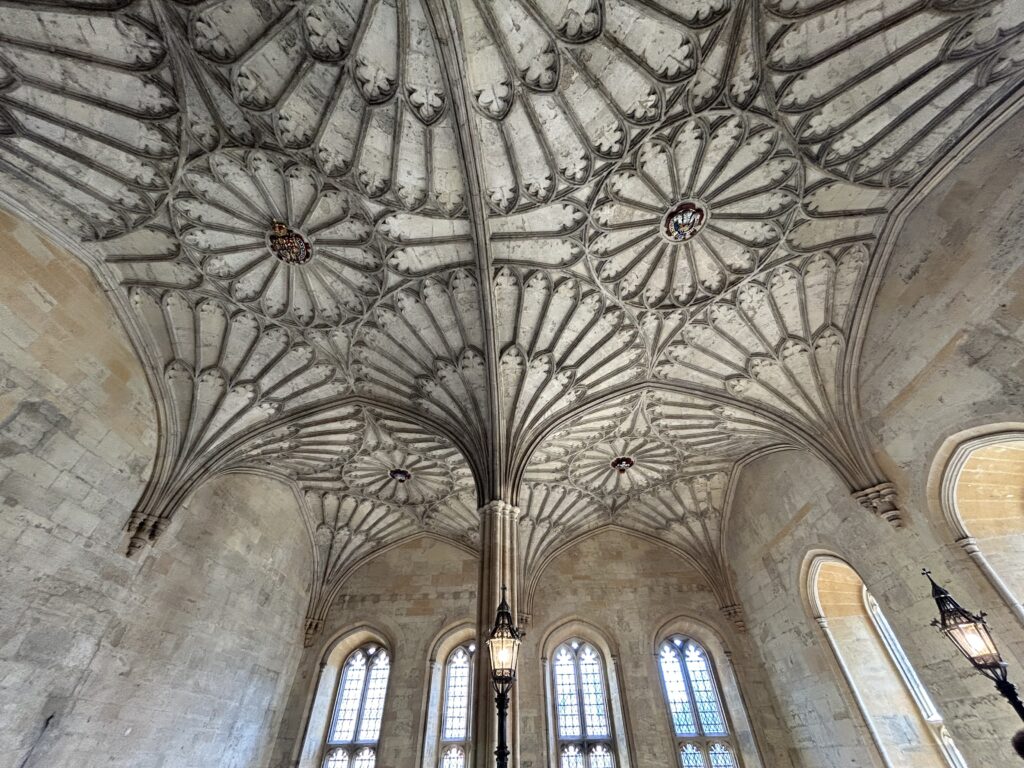

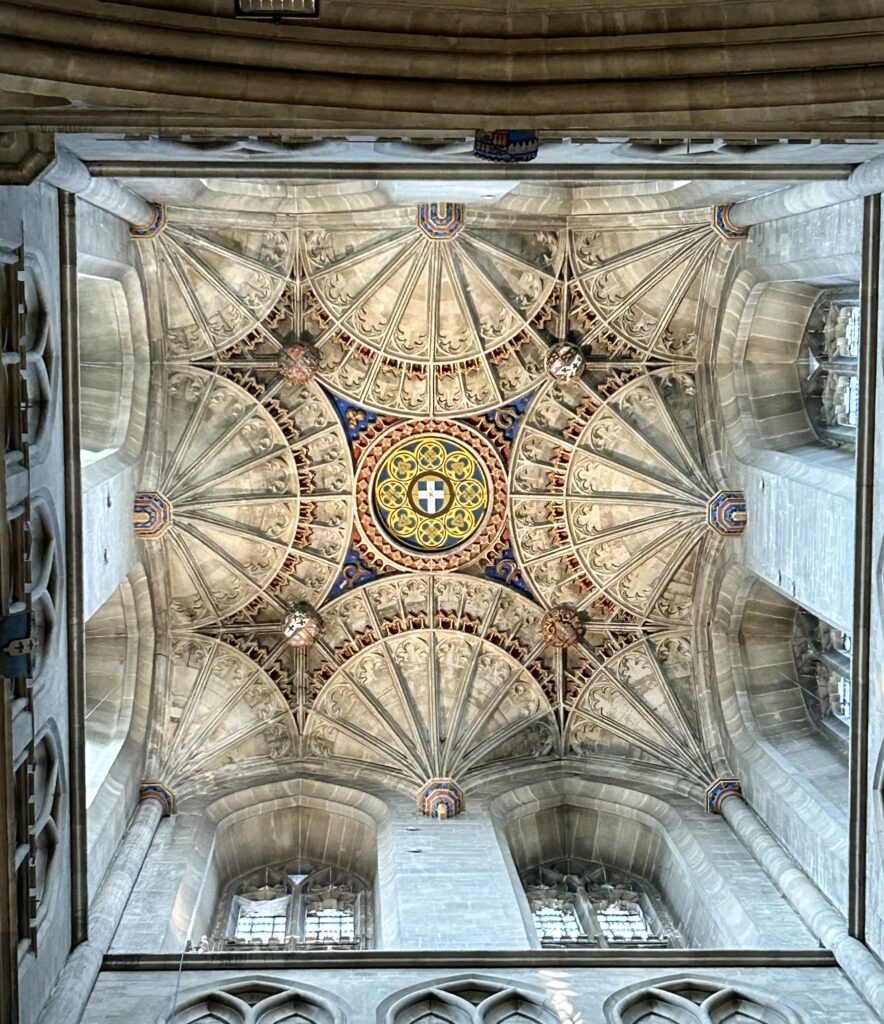

England was a RUSH but a wonderful one. My first day in the UK, I dropped my bags in London and travelled 2+ hours out of the city to visit the Royal Albert Memorial Museum in Exeter. Here I viewed “Criminal Ornamentation,” an exhibition curated by British-Nigerian artist Yinka Shonibare. Boyce’s 1986 drawing Lay back, keep quiet and think of what made Britain so great was a part of this show. Lay back, keep quiet and think of what made Britain so great was the work which first introduced me to Boyce, so it was moving to begin my travels by seeing this piece.

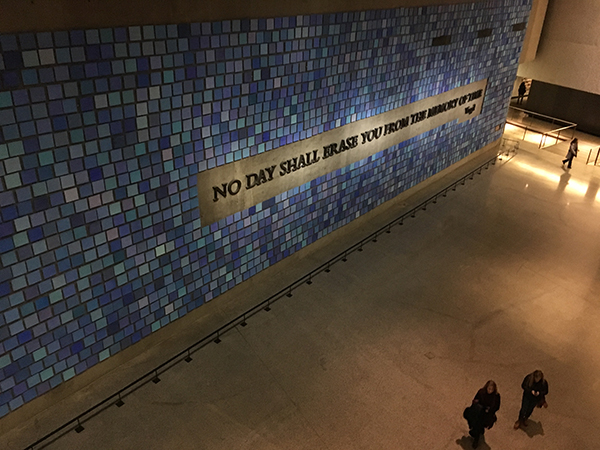

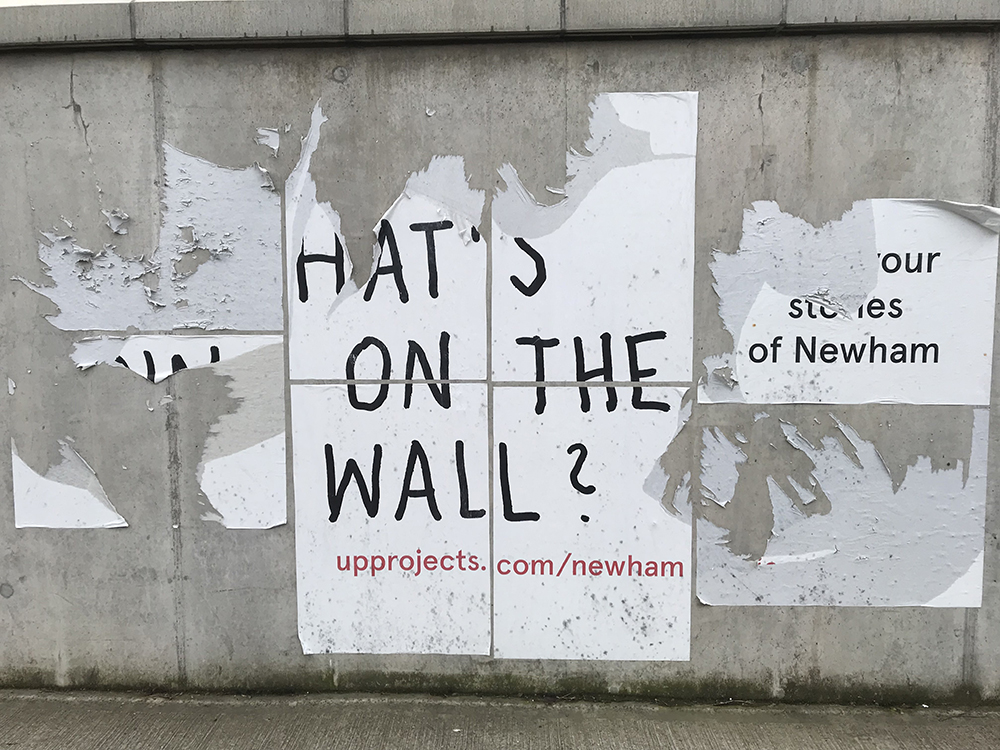

A section of the Newham Trackside Wall, now empty. Sonia Boyce’s collaborative design will be installed on this surface before the end of 2019.

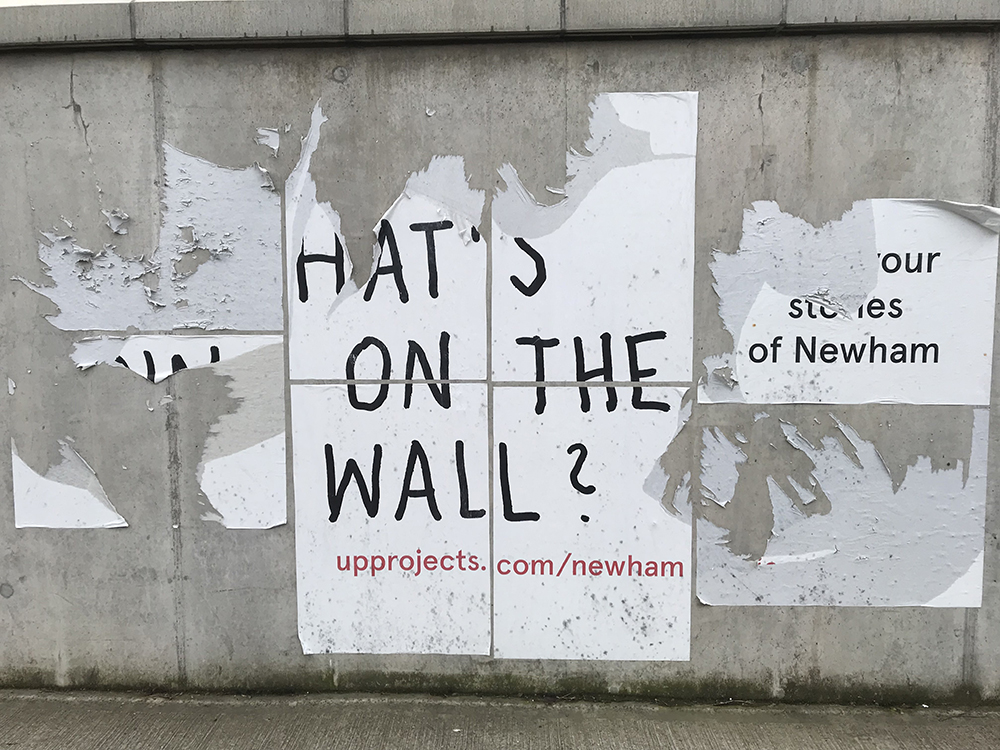

Over the next two days, I ebbed and flowed around and out of London. I had the chance to visit the Arts Council Collection where Curator, Beth Hughes generously pulled Boyce’s 2010 etching I Have Found a Song for me. On another day, UP Project’s Commissions Curator, Niamh Sullivan introduced me to Boyce’s current commission project, the Newham Trackside Wall. Due for completion in 2019, the Newham Trackside Wall will be the longest public artwork ever made in the UK, stretching over a mile long. Additional stops included the British Museum, The Lightbox gallery in Woking where Boyce’ work From Tarzan to Rambo: English Born ‘Native’ Considers her Relationship to the Constructed/Self Image and her Roots in Reconstruction was on view as part of an exhibition, and a detour to the Young Vik to see a one-man show by the actor who famously cried “You shall not pass!” to protect a band of hobbits.

A section of the Newham Trackside Wall with remnants of wallpaper promoting the commission project.

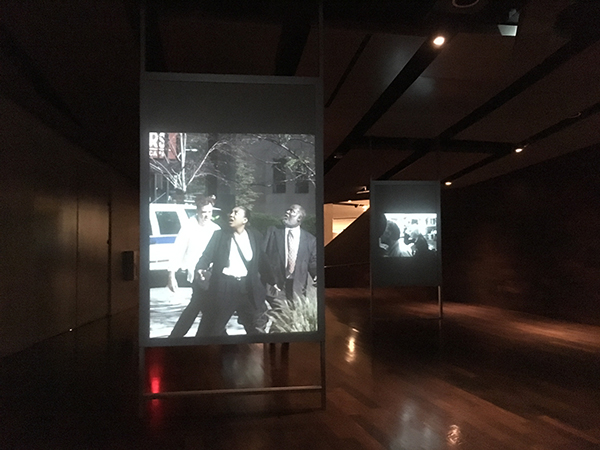

Following this run, I took the weekend to explore Birmingham and Manchester. In Birmingham, one highlight was seeing the exhibition “Women Power Protest.” Boyce’s 1985 drawing Mr. Close Friend-of-the-Family Pays a Visit Whilst Everyone Else is Out was on display here. A second highlight was visiting EastSide Projects and meeting Director Gavin Wade. Mr. Wade was kind enough to tour me through what the space was like when Boyce held her 2017 Wallpaper / Performance sessions at the gallery. In Manchester, the main stop was – as should come as no surprise – the art gallery. What did come as a surprise, however, was seeing Boyce’s 2018 work Six Acts on view as part of the permanent collection. This was the first material wallpaper by Boyce I had seen in-person; better still, it was installed and on view in a public space.

An educational panel of the “History of Black Britain” on display at the Black Cultural Archives in London.

Returning to London, there was a lot to take in from the weekend, but a lot left to see and do over my last two days. Visits were made to the John Soane Museum, the Tate Modern, the Whitechapel Gallery, the Black Cultural Archives, and the Victoria & Albert Museum – where I was lucky enough to view an assortment of wallpaper samples, by Boyce and others, thanks to Senior Curator of Prints, Gill Saunders. Another thanks is due to Curator Claire FitzGerald of the Government Art Collection who led me past security and guards to see a large screenprint of Boyce’s Devotional chart in the Foreign and Commonwealth Offices. Of course, the trip came full circle by having the chance to meet Sonia in person. We met at the Royal Academy and she treated me to English cake and tea, a welcomed refreshment for one too nervous to eat anything beforehand. There may not have been any icing on the cake, I can’t remember, but none was needed. My thanks to all who in their generosity made this trip more than I could have hoped or imagined.