Alex Kermes is an art history graduate student completing his qualifying paper on the 19th century painter, Joshua Johnson. He was awarded the Art History Department Graduate Research Grant to help make this project possible. Alex will be presenting his qualifying paper research at the Art History Graduate Forum on December 18.

Joshua Johnson, the topic of study for my Qualifying Paper, is an enigmatic figure since so much of his life is unknown. Few details have trickled down from decades of scholarship on Johnson, who is considered the first African American portraitist in the U.S. I experienced this enigma firsthand while conducting research on him, and felt the department’s travel grant would help me uncover a great deal more.

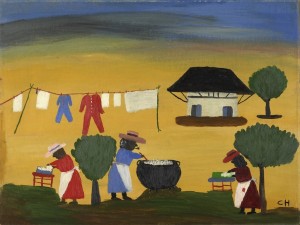

Johnson lived and worked in Baltimore, actively painting portraits of middle and upper class clientele from the late-1790s to mid-1820s. Although he owed much to the influence of painters around him, he devised a style all his own. His paintings are characterized by thin layering of oil paint, minimal shading on his subjects (often children), and frequent use of props.

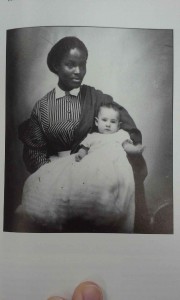

The third largest city in the U.S. during this period, Baltimore had an active African American population, both slave and free. Citizens interacted with a diverse population, and my research has focused on how Johnson responded to such diversity – in spite of the limited sources. The travel grant helped me understand Johnson as a person, living and working as an artisan in a time defined by slave and free status.

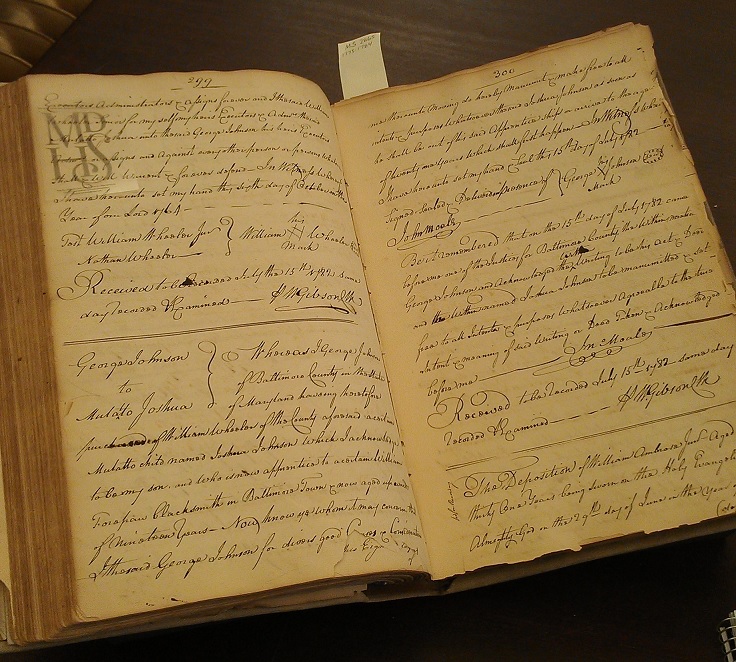

The reality of slavery sunk in while I dug deep into the sources in the Maryland Historical Society’s (MHS) library archives. While there, I read a manifest from the 1780s containing all sorts of transactions in Baltimore, including the legal documentation that set Johnson free from slavery. On one hand, it was an important record to look at closely as it assigned the conditions for which Johnson would become free, while on the other hand, these same pages contained transactions for horses, livestock, and ships in the harbor. This provided a disheartening reminder about a significant segment of America’s history.

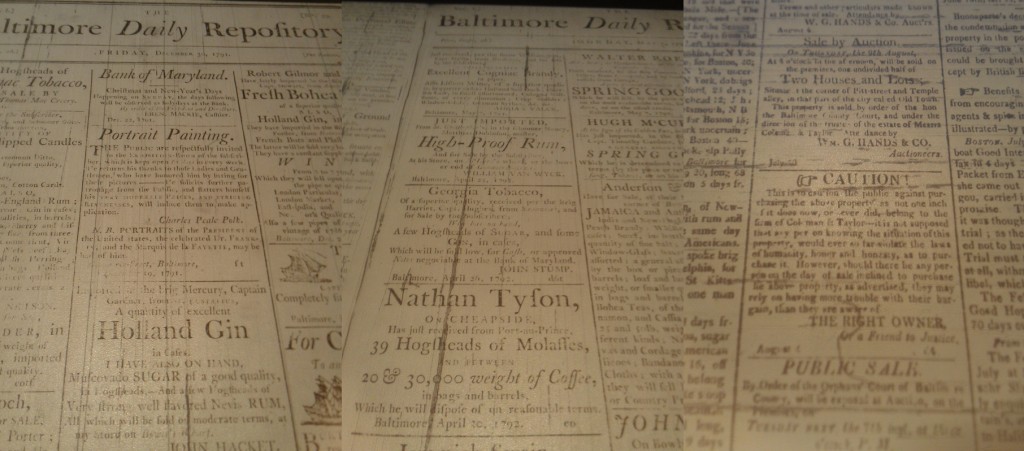

Still, the MHS provided me with a wealth of details that helped me piece together a personal history of Johnson’s life. I looked at newspaper advertisements of other artisans and city directories that listed Johnson’s various residences throughout his life in the 1800s.

As an art historian, it was important that I see his work in person and up close, and there are far more of his paintings in Baltimore than the St. Paul-Minneapolis area. The Maryland Historical Society is home to a few, though they have a strict photography policy, and other can be found at the Baltimore Museum of Art. I spent time at both to examine Johnson’s works, and simply because both are quite fabulous museums.

While drafting the prospectus for my qualifying paper, one of the major comments I received stressed the importance of bringing his works forward in my discussion. My focus had drifted too far into Johnson’s context that his actual paintings took on a seemingly secondary role. Studying his works in person changed that remarkably. The subtle ways he handled his paint differ throughout the periods of his career, making it possible to identify a Johnson work from 1804 versus one from 1814. This spoke a great deal to me about the work he received during this period and how he was able to hone his craft.

Joshua Johnson, James McCormick Family, 1804-5, 50 x 69 in., Maryland Historical Society, oil on canvas (left); Joshua Johnson, Rebecca Myring Everette and her children, 1818, 55 x 58 in., Maryland Historical Society, oil on canvas (right)

Of course, Baltimore is culturally and historically significant, which meant on my free evenings (the MHS is open only until 5:00), I saw the U.S.S. Constellation parked in the harbor, poked my head in the Walters Art Museum which was located next to the MHS, and wandered the Baltimore Museum of Art’s galleries.

I certainly could have completed my Qualifying Paper without this research travel grant. Yet, studying Joshua Johnson’s Baltimore in person has given me tremendous insight into his life and what his career in painting was all about. Walking along High Street, close to the harbor, I could almost sense where Johnson might have lived and worked in the first decade of the 19th century. I truly built a personal connection to Johnson and his work by studying him on my Baltimore trip, and it increased my quality of research. My Qualifying Paper has already greatly benefited from every additional page of notes I took while in the archives and viewing his paintings and digging through the Maryland Historical Society’s archives – progress that I could not have made without the travel grant. Visiting Baltimore has made him much less the enigma he was when I began my research.