Clare Monardo is an art history graduate student currently completing her qualifying paper on the Irish Holy Wells of St. Brigid. She was awarded the Art History Department Graduate Research Grant to help make this project possible. Clare will present her paper at the Fall 2016 Graduate Student Forum on Dec. 16th.

This summer I was fortunate to be able to travel around Ireland for three weeks researching the holy wells of St. Brigid in Ireland, which is the topic of my qualifying paper for this program. I have been exploring the St. Brigid’s holy wells for two years now and had hit a wall due to a lack of photographs and site-specific records, prompting this trip.

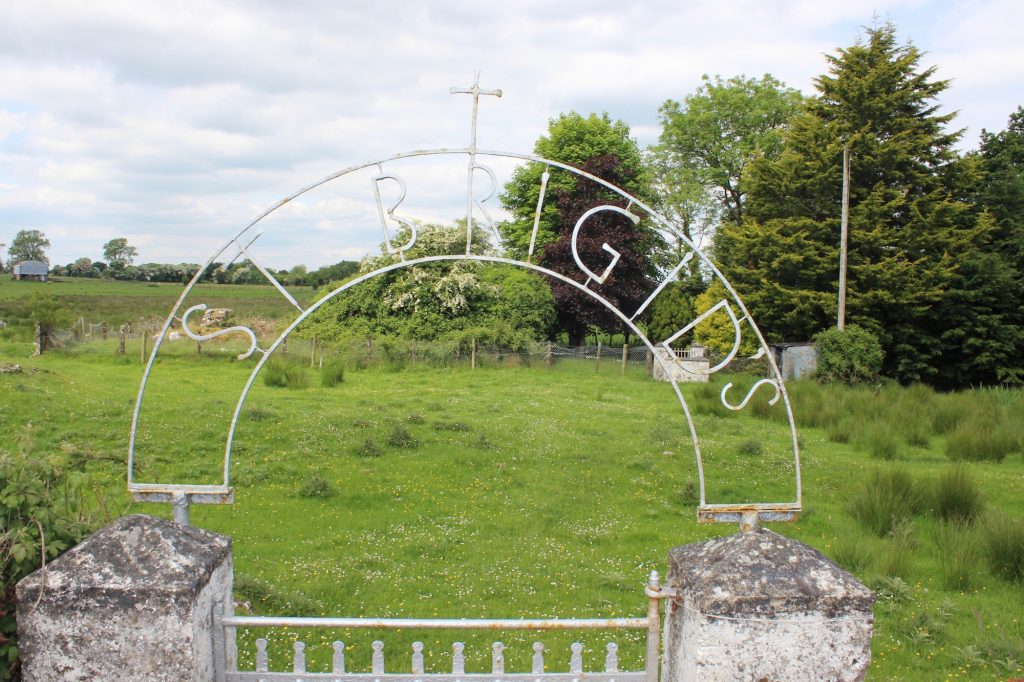

A sign marks St. Brigid’s Well, Killare, County Westmeath. In order to access the holy well, which is located in a copse of trees, visitors must walk through a field of grazing sheep. Photograph taken by author on June 4, 2016.

Holy wells are noteworthy settings because, in addition to being semi-man-made places of prayer and contemplation out in nature, many of them are believed to cure physical ailments in addition to spiritual ones. Almost every town in Ireland has at least one holy well, with some counties having upwards of one hundred, for a total of approximately three thousand wells in the country as a whole. The landscape in which holy wells reside shows an amalgamation of pre-Christian and Christian practice and have been enhanced by man-made additions such as signs, well-houses, paved paths, shrines, and the Stations of the Cross.

Stations of the Cross at St. Brigid’s Well in Cullion, County Westmeath. A path allows visitors to circumambulate the well while praying the Stations of the Cross. Photograph taken by author on June 4, 2016.

Throughout the course of my research I have come across one hundred holy wells dedicated to St. Brigid in Ireland, not all of which are still in use today. I was able to visit ten of these holy wells while in Ireland, along with local libraries, historical sites, and the Solas Bhríde center in Kildare run by Brigidine nuns. My qualifying paper focuses on four sites, located throughout the country: two wells in Tully, County Kildare; one in Ballysteen, County Clare; one in Faughart, County Louth. These four holy wells were chosen because of their popularity, the fact that they are still venerated today, and because the greatest amount of information regarding the Irish holy wells of St. Brigid focuses on these particular sites. Some of the holy wells that I visited were clearly marked and had road signs pointing the way, making them easy to find. Others, however, were not so obvious, leading to lots of extra driving around (which was already somewhat stressful as it’s on the opposite side of the road from what we’re used to!) and eventually having to ask for directions from locals. These included the St. Brigid’s Well in the Faughart graveyard and another located down the road from Raffony Graveyard.

A stone beehive hut encloses St. Brigid’s Well in Faughart, County Louth, and there are steep steps going down to the water. To the left of the well are clootie trees. Photograph taken by author on June 12, 2016.

Tucked into a hillside down the road from Raffony Graveyard is St. Brigid’s Well, Raffony, County Cavan. Photograph taken by author on June 10, 2016.

Two holy wells associated with St. Brigid, known as St. Brigid’s Well and St. Brigid’s Wayside Well are located in Tully, County Kildare. Both of these sites are still visited today, but the popularity of the Wayside Well has diminished in recent decades with the renovations of the nearby St. Brigid’s Well.

St. Brigid’s Wayside Well in Tully, County Kildare. Stone steps lead down to the murky and stagnant water, and a small amount of clooties and other items point to this well still being a place of veneration. Photograph taken by author on May 30, 2016.

Ritual is an integral part of the holy well experience and it can involve not just the holy well, but also sacred trees and stones. Oftentimes trees nearby holy wells have pieces of cloth, called clooties, tied to their branches, marking them as being venerated. When visiting a holy well the afflicted takes a piece of his or her clothing and ties it to the tree with the belief that the disease which is plaguing them will be transferred from their body to the tree.

Located at the back of the axial site is St. Brigid’s Well. To the left of the well is a clootie tree with colorful ribbons and pieces of cloth tied to its branches. Tully, County Kildare. Photograph taken by author on June 1, 2016.

A small bridge passes over the stream at St. Brigid’s Well in Tully, allowing visitors to access the clootie bush on the right and the statue of St. Brigid on the left. Photograph taken by author on May 30, 2016.

In addition to clooties, it has become quite common for visitors to leave a variety of other objects at holy wells. St. Bridget’s Well in Ballysteen, County Clare had the largest accumulation and assortment of items that I came across during my trip. Not only were there prayer and memorial cards, but also religious statues and images, rosaries, photographs, flowers, religious medals, an empty vodka bottle, a pair of children’s shoes, and a sparkly hula-hoop.

At St. Bridget’s Well, Ballysteen, County Clare, access to the holy water is gained by entering a whitewashed well-house that surrounds the well and proceeding down a dark and narrow passage. Multiple layers of votive offerings have built up inside the well-house. Photograph taken by author on June 8, 2016.

By going on this research trip I not only was able to access local sources that had been unavailable to me previously, but I also gained a better sense of how one is supposed to move through and use the space of holy well sites. Information from both types of visits will help me understand how ritual and space affect and inform one another at the holy wells of St. Brigid in Ireland as I continue to move forward with my qualifying paper.