Nicole Sheridan is an art history graduate student completing her second year. She was awarded the National Endowment for the Humanities We the People Fellowship in African American History, for study at the John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library in Colonial Williamsburg, Virginia.

In January 2016, I had the privilege of conducting research in Colonial Williamsburg, Virginia with the support of a National Endowment for the Humanities “We the People Fellowship in African American History and Culture.”

Residency cottage

Living room of the colonial style residency cottage

I began this project in my spring 2014 graduate seminar on the African Diaspora, taught by Dr. Heather Shirey. One of our assignments involved creating a research grant proposal, and we were encouraged to seek out actual funding sources from external institution. Dr. Shirey provided students with examples of grant proposals, including both those that had been accepted and declined. These examples helped me recognize differences in writing style, language, and clarity of expression in relation to the projects’ feasibility. I realized I needed to write a proposal that was forward and bold. I decided to investigate a topic that combined two interesting subjects: the historical mammy, and nineteenth-century doll representations.

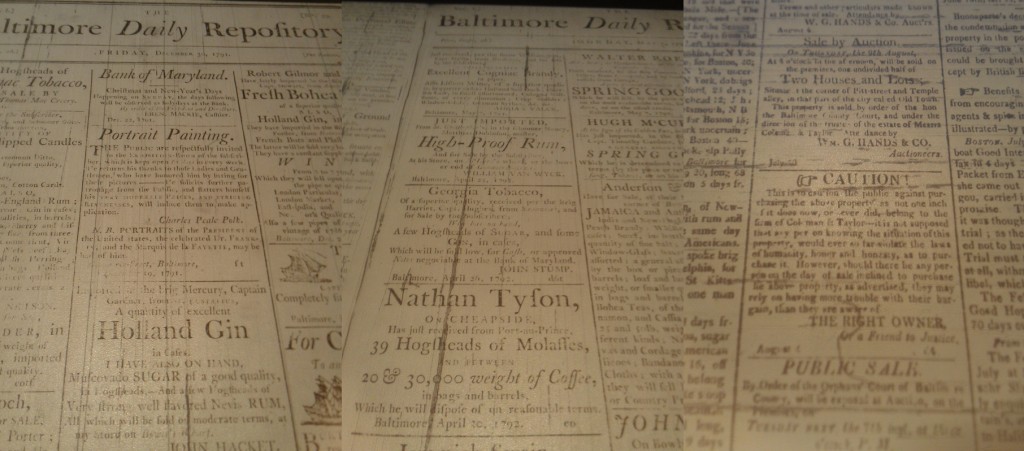

Once I had identified an appropriate funding source, I perused the webpages of the John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library and Archives, as well as the Dewitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum and the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum. I realized that connecting my project to the holdings of the institution’s on-site resources would be essential in arguing my claim to travel to this particular location. During my search, I was intrigued by an online collection featuring toys, in particular a mammy doll with a head composed of a walnut. This struck me as a peculiar material for a doll held in a museum, so I decided to investigate.

Mammy Nut Doll, c.1840-1899

Hickory nut, leather, wire, textiles, horse hair, paint

Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum

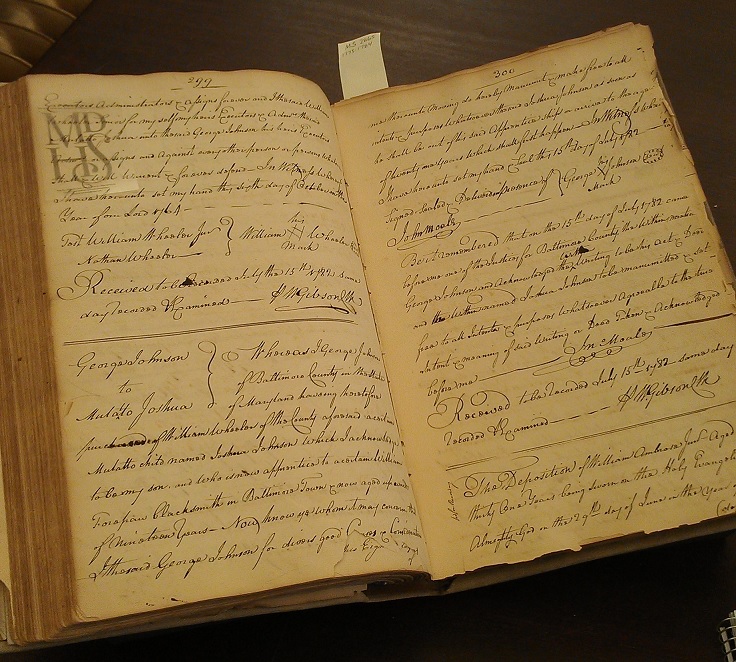

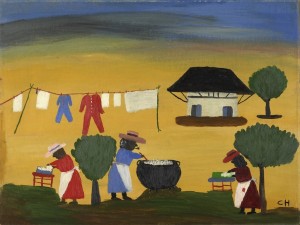

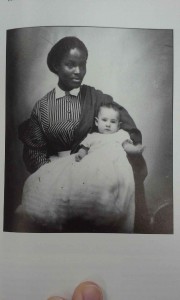

The term mammy refers to a racist stereotype of the household slave responsible for childcare, cooking, and cleaning. Her image is recognizable as an obese female with jet-black skin, large lips and eyes, a head turban, an apron, and colorful calico clothing. This nineteenth-century archetype manifested in the image of Aunt Jemima at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago through the actress Nancy Green. Early on, I had a hunch that the use of such a humble material was linked to creators of low economic status, and that a black doll was more likely made by an adult or child of color. Thus, I was puzzled by a notion of African Americans participating in creating the mammy stereotype. Centering my project on this doll, which exhibits characteristics of the mammy figure and use of material culture, I devised a research topic that explored a number of issues, including the history of the mammy figure, nineteenth-century dress of indoor slave staff, mammy doll characteristics and constructions (with and without nut heads), and children’s culture of the nineteenth century including child slavery, play, and doll types. Through this contextual research, I also sought to understand the involvement of African American women and children in creating mammy dolls. Visiting local archives was helpful in providing empirical materials including extant mammy dolls, and photographs of dolls and nineteenth century mammies.

-

-

Mammy Topsy-Turvy Doll , 19th c., Valentine Richmond History Center.

Upon visual examination, we discovered this mammy doll had a surprise underneath the dress, an attached white doll (image on right), making this a Topsy-Turvy doll.

-

-

Reverse side of Mammy Topsy-Turvy Doll

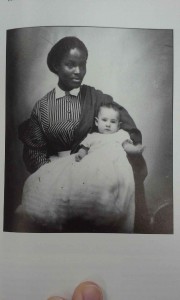

Mammy with baby, July 1868

Courtesy of the Valentine Richmond History Center

At times difficult to swallow because it is so painful, the history of the mammy figure, including black culture apart from and including whites, was fascinating as the stories of past lives seemed to leap from the pages. My research illuminated the horrors of slavery as well as evidence of intense courage and perseverance. As a developing art historian, reading slave narratives affected me both personally and professionally.

The month long fellowship program also gave me the opportunity to deliver in a public forum. For this presentation, I provided the background for my topic, outlined the goals of and resources for my project, and shared my research questions. There was a great turnout of guests who shared my curiosity in the topic and added to a lively discussion.

The most difficult aspect of the fellowship was being away from home for a long period. Thankfully, the staff at Colonial Williamsburg were welcoming and helpful. Early on, Ted Maris-Wolf, the head of research initiatives for the Rockefeller Library, assisted me in locating relevant local resources. I was fortunate to have the opportunity to conduct research alongside Linda Bergmuten, the Head Curator of textiles and costumes. Linda provided me with extant high-class dress materials as well as working women’s dress, aiding with the analysis of garment dating, and edifying the accuracies and divergences from actual mammy dress. This information proved beneficial in providing me with further clues to distinguish clothing differences between women slaves working outdoors and that of indoor slaves, in which the mammy was included.

19th c. working women’s shirt, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Jan Gilliam, the Associate Curator of the toy collection, granted me access to examine the mammy doll as well as other relevant black dolls held in the collection. Viewing the mammy nut doll in person provided me with information the photograph could not illuminate. For example, the doll was smaller than I had imagined, perhaps slightly larger than dollhouse dolls. In hopes of revealing clues to the doll’s construction, Linda and Jan performed a fabric analysis of the interior of the doll’s body. After struggling with the tiniest of tweezers to acquire interior material through the back leg, Linda was not able to extract an example. Though initially disappointing, it did in fact reveal that the interior is quite likely wound around a skeleton made most likely of wire. In addition and as a surprise to both the curators and myself, there was a note tucked inside the doll’s blouse, providing yet another clue towards understanding this particular doll.

Curators performing the fabric analysis, which led to finding a note tucked inside.

I also had the privilege of meeting the other research fellow, Kristin, whom had recently received her PhD in History from Washington University. Dr. Condatta-Lee was conducting research for the first chapter of her book, exploring foreign imports brought with early Irish settlers to New Orleans. It was great getting to know her and supporting each other in our research quests.

Exploring the town of Colonial Williamsburg with fellow Kristin (on right)

A major ambition of the project was to define my research in terms of how exactly I was to utilize the little extant evidence of this area of folk material culture. This was begun through seeking out extant dolls that fit the criteria of a mammy figure, which proved more difficult than I had imagined. Not all dolls of black women could be included in my taxonomy of extant mammy dolls unless they displayed qualities distinctive to the image of an indoor worker. This type of doll exists in very small museums and private collections. Likely, the topic of mammy dolls has not received attention namely because of such difficulty in accessing extant dolls. For this reason, I will be extending this research into an independent study to add onto my taxonomy of dolls and in hopes of sharing my findings. Willingness to travel and openness to new professional experiences build a well-rounded graduate education and enrich your current skills. Grand aspirations come within reach when paired with extra effort and determination.