Harrison Peck is an Art History/Archaeology Graduate student at the University of St. Thomas. His work over the summer of 2024 in Sveti Klement, Croatia was focused on the archaeological site at Soline Bay under professors Ivancica Schrunk and Vanessa Rousseau. His areas of focus in academics are Republican Rome and Early America, and he is particularly interested in archaeology and museum administration.

During the 2024 excavation at Soline Bay, Harrison worked with a Roman site that likely produced salt, wine, olive oil, and garum (a type of fish-sauce). He also assisted with both the actual excavation and the cleaning and organizing process afterwards on-site. This project followed an interdisciplinary approach through combined work from staff, faculty, and students with a variety of backgrounds in archaeology, history, geology, and art history. Harrison’s overall project focus for this season was the field of museum ethics and cultural heritage. Specifically, he analyzed museum methodology, cultural approaches toward history, and Croatian cultural property laws to identify how different countries both recognize and utilize historical and archaeological sites/objects.

The project’s initial stages involved setting up the excavation site and estimating the location of the old Roman wall. The located wall was in much better condition than expected – walls from the early Roman period are usually better cut than those from later periods and were almost always repurposed for other structures. Excavation continued to the lower layers where the digging ran close to bedrock and the wall’s foundation could be identified, which took most of the remaining time that had been allotted for the dig. The excavation team had other projects running alongside the primary excavation, which members of the crew assisted with as needed.

The project’s initial stages involved setting up the excavation site and estimating the location of the old Roman wall. The located wall was in much better condition than expected – walls from the early Roman period are usually better cut than those from later periods and were almost always repurposed for other structures. Excavation continued to the lower layers where the digging ran close to bedrock and the wall’s foundation could be identified, which took most of the remaining time that had been allotted for the dig. The excavation team had other projects running alongside the primary excavation, which members of the crew assisted with as needed.

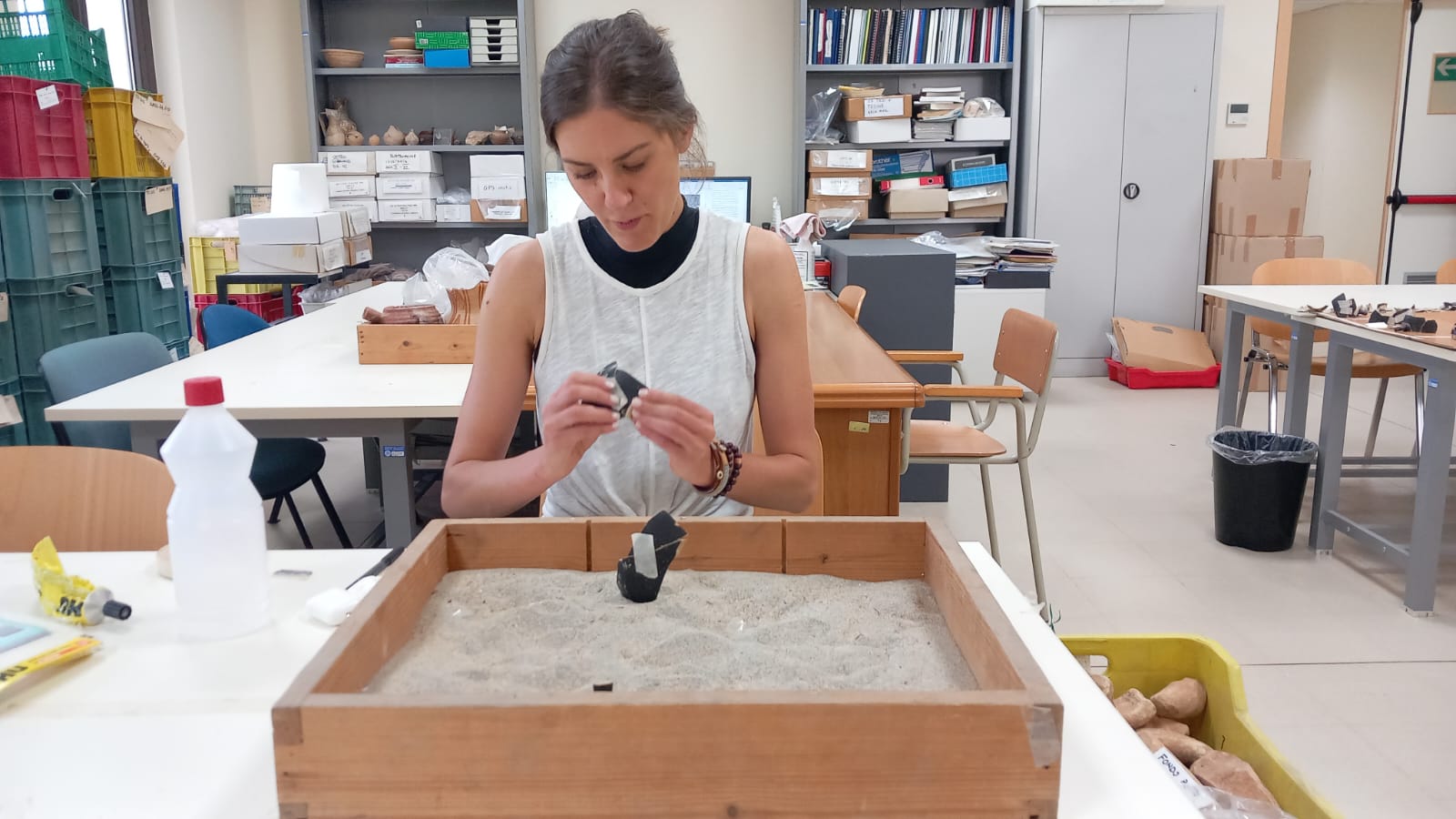

The geology team focused on core sampling and surveying, which added to the knowledge of the site’s geographic evolution; other areas of the site were cleared of brush and debris to allow for surface level examination. During the excavation, Harrison assisted Tom Schrunk with the archaeological photography of the site, taking photos and measurements of both the primary excavation and other areas. Toward the end of the excavation, the crew worked to clean and organize discovered pottery by layer, allowing future research to more easily examine the material and conclude roughly when and where it was deposited. The dig concluded with laying geocloth and backfilling the site to protect the old Roman wall. Discoveries from this year’s dig include a large number of tesserae (rectangularly-cut pieces of stone used to create mosaics), an ancient coin, and some fresco work. Additionally, they uncovered a great deal of different types of pottery; some retained slip, others were likely locally-made, and still others were imported, as they contained clay types identified as coming from the Levant and other areas.

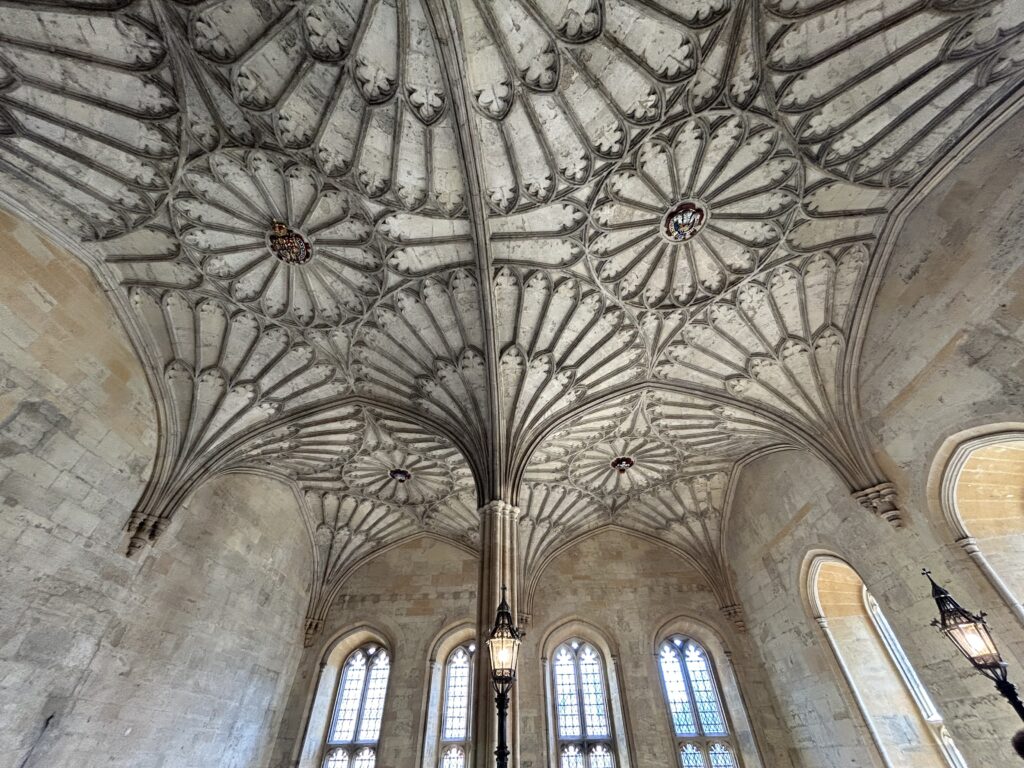

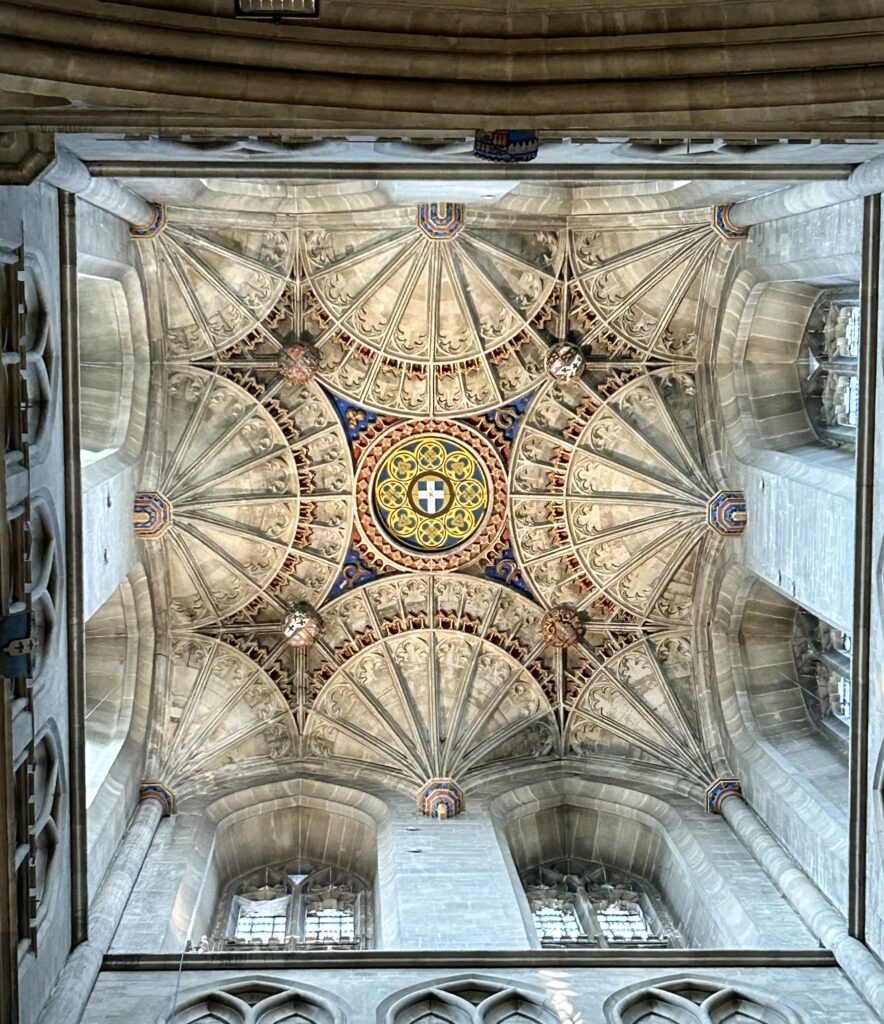

At three points during the trip (before, during, and after the excavation), Harrison visited museums, archaeological archives, and local tourism-oriented sites of historical influence to investigate the cultural use of historical objects and their roles in modern Croatian culture. During these trips, he spoke with a number of experts including archaeologists, divers, museum managers, and curators to investigate Croatian cultural heritage laws and their application. The combined experience of the museum studies element and the excavation itself provided Harrison with a solid foundation for both museum-centric cultural heritage theory and hands-on archaeological experience.

The project’s initial stages involved setting up the excavation site and estimating the location of the old Roman wall. The located wall was in much better condition than expected – walls from the early Roman period are usually better cut than those from later periods and were almost always repurposed for other structures. Excavation continued to the lower layers where the digging ran close to bedrock and the wall’s foundation could be identified, which took most of the remaining time that had been allotted for the dig. The excavation team had other projects running alongside the primary excavation, which members of the crew assisted with as needed.

The project’s initial stages involved setting up the excavation site and estimating the location of the old Roman wall. The located wall was in much better condition than expected – walls from the early Roman period are usually better cut than those from later periods and were almost always repurposed for other structures. Excavation continued to the lower layers where the digging ran close to bedrock and the wall’s foundation could be identified, which took most of the remaining time that had been allotted for the dig. The excavation team had other projects running alongside the primary excavation, which members of the crew assisted with as needed.