‘Of Note’ is a new series showcasing what members of the Department of Art History have been up to and will be published at the start of every semester. If you have something that you would like included in the next post, please send it to Marria Thompson.

Dr. Andy Barnes

This summer I undertook a driving tour of the lowland Maya region of Mexico. While crossing through the states of Quintana Roo, Yucatan, Campeche, Tabasco, and Chiapas, my trip included stops at Tulum, Chichen Itza, Uxmal, Merida, Campeche (city), Palenque, and Calakmul. Pictured here is the textile inspired façade of one of the structures in Uxmal’s grand Nunnery Complex (ca. AD 900) and Structure II, Calakmul (begun before AD 100 and enlarged considerably over the following seven centuries). Calakmul, in Campeche State, is one of the largest Maya sites, which flourished between AD 600-900. Structure II, standing over 15 stories tall, is one of the largest pyramids in the Maya region (it is somewhat larger than the Pyramid of the Moon at Teotihuacan).

Dr. Craig Eliason

This summer I attended the Granshan Type Design Conference in Reading, England. The theme of the conference was “global design in practice,” and the program included a terrific presentation by Korean calligrapher Kang Byung-in. Then, that evening, the conference moved to the University’s typography department, where sheets of paper were set up for a giant-scale, joint calligraphy demonstration by Kang and English calligrapher Timothy Donaldson. The packed room watched as the two men went at it with all manner of pens and brushes, showing off both craft mastery and a little clownish rivalry. The demonstration ended with both artists dipping their hands directly in the ink, making handprints on the paper, and then shaking hands.

Calligraphy demonstration

Dr. Eric Kjellgren

In August, I traveled to Australia at the invitation of the National Gallery of Australia and the Oceanic Art Society to give a presentation at the Art of the Sepik River Forum held in conjunction with a newly opened exhibition of art from the Sepik River in northeast New Guinea at the gallery in Australia’s capitol city of Canberra. My paper Hidden “Hands”: Searching for the Artist in the Arts of the Sepik River explored the idea that works by individual artists can be identified within the arts of the Sepik River, something that has not previously been done for this art-rich region of New Guinea.

Eric Kjellgren with Pacific Art Curator Crispin Howarth (left in navy blue blazer) and members of the Oceanic Art Society examining works at the National Gallery of Australia

Dr. Heather Shirey

This summer I presented a paper at the Transatlantic Dialogues conference in Liverpool. Liverpool’s Lord Mayor hosted a reception for attendees as a special event during the conference. This reception took place at Liverpool’s beautiful, 18th century Town Hall. By complete accident, I arrived at the reception a half an hour early, along with a friend I had made at the conference. After overcoming some initial suspicions due to our early arrival, the building director invited us to take advantage of the special opportunity to visit the building, which is only open to the public once a month. Learning that we were art historians, he suggested that we wander through the ground floor rooms to see the city’s art collection. On our unguided wanderings, we first stumbled into the Council Chamber, where the Lord Mayor himself happened to be visiting with a few of his constituents. He very kindly invited us to try out the seat reserved for the mayor in the council room. I think a room like this would be just spectacular for our seminars!

Heather seated in the Liverpool Town Hall Council Room

Next we stumbled across a portrait of John Archer, said to be (although this is debated) Britain’s first mayor of African Descent. Born in Liverpool, Archer traveled to the United States and Canada before being elected Mayor of Battersea in 1913. The painting, by Paul Clarkson, incorporates references to African American intellectual and cultural movements: Archer rests his arm on a copy of The Crisis, the official publication of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored people, and a poster advertising the Fisk Jubilee Singers hangs behind his head. I am interested in the ways that Archer himself evoked symbols of the battle for civil rights in the United States in his own political career. I also want to learn more about the position of Archer in Liverpool’s contemporary interpretation of the city’s racial dynamics. The city of Liverpool and its many citizens amassed tremendous wealth during the eighteenth century due to the city’s important position as a port during the height of the transatlantic slave trade. Just down the road from the Town Hall is the International Slavery Museum, which grapples with this aspect of Liverpool’s history. It is worth noting that this painting was installed in the Town Hall only within the last decade. What does this current interest in John Archer tell us about Liverpool’s evolving understanding of its past?

Portrait of John Archer

Margaret George, graduate student

Summer, travel, and art are intertwined in my vocabulary. As I prepared for this fall’s Contemporary Architecture class, I was excited to spend some time this summer in Buffalo, New York . The city has some wonderful architecture in its downtown including a pretty spectacular building by Louis Sullivan, the Prudential Guaranty Building, designed in 1894-85 (left image). The stone and detail on the building were just beautiful – almost exquisite. An architectural contrast was a Rem Koolhaas’ 21st century building (CCTV Headquarters) in Beijing that I also saw this summer (right image). “Big Boxer Shorts” as the locals call it – you can figure out why.

Amanda Lesnikowski, graduate student

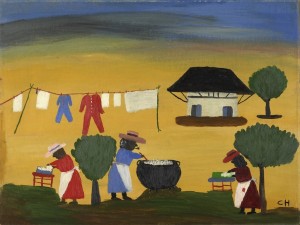

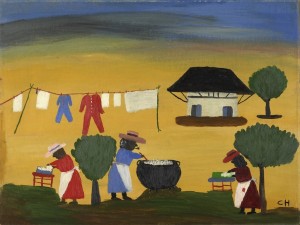

I never truly appreciated the saying “kill two birds with one stone” until I found myself in a masters program and a full-time job at the same time. This summer, while working under the direction of Dr. Heather Shirey, I completed an independent study that focused on the development of an African American Art Teacher Resource guide for elementary school teachers. I began by selecting five artworks from the Minneapolis Institute of Art’s permanent collection. I researched the artists and their artworks, then aligned state academic standards with a set of open-ended questions to create a resource guide that can be used by teachers across the state. It was an amazing feeling to watch my two ‘jobs’ become one.

Clementine Hunter, The Wash, 1950s, Oil on board, 18 x 24 in. (45.7 x 61.0 cm)

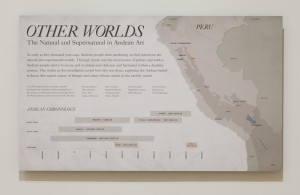

Dakota Passariello, graduate student

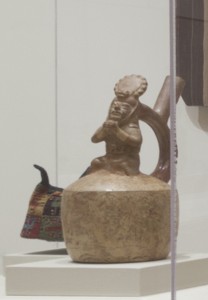

This June I began an internship at the Thrivent Financial Collection of Religious Art. In the past few months I have been working with the collection and its curator, Joanna Lindell. Thus far, I have been exposed to and have learned a tremendous amount about the multifaceted world of curatorial work. Some of my tasks and experiences so far have included assisting the curator with planning an exhibition layout, writing and fabricating object labels and exhibition panels, and attending meetings related to upcoming events and plans for the gallery. Thrivent has a truly special collection that is globally recognized; yet I think the collection is largely overlooked by our own community. If you haven’t been, I highly recommend coming to check out the gallery! It’s free!