On Tuesday, April 17, the University of St. Thomas Department of Art History hosted an event that was part celebration, part symposium, part demo, and part product-reveal party. The product being revealed, the subject of conversation, and cause for celebration, was the department’s collaboration with Voorsanger Architects PC of New York; the Voorsanger Architects Archive serves as an educational resource for the department and a model (and test case) for digital preservation moving forward.

Tuesday’s event, billed as A Conversation about Architectural Legacy, featured architect Bartholomew Voorsanger, FAIA, in conversation with noted architectural historian Dr. Dell Upton and St. Thomas’ own Dr. Victoria Young. Dr. Upton walked Voorsanger through some of the greatest hits of his firm’s designs (most notably the National World War II Museum in New Orleans, establishing why Voorsanger and his firm are worthy of archiving; Dr. Young focused on the archive itself, examining both its features and the process through which it was created, thanking Christine Dent and several graduate student assistants.

Also present was Dr. Ann Whiteside, librarian and assistant dean of Harvard’s graduate school of design. Whiteside, an expert in digital archives and their attendant issues, noted that the world of design faces a mounting problem, with over 40 years of digital design documents, many of them in proprietary file formats (in other words, formats that can only be read by the specialized software used by a particular firm), piling up and creating a nest of archival problems that simply didn’t exist when design was done on paper (problems such as: how do you make sure these file formats will still be readable in 30 years? What type of file-corruption risks exists with different types of digital storage? How do you protect digital archives from accidental loss or erasure?). Whiteside is involved with the Building for Tomorrow project, which seeks to bring people from different sides of the issue (archivists, designers, academics, IT experts) together to find solutions for archives and museums, believing that collaboration is necessary for success.

Along those lines, Whiteside cited the Voorsanger Architects Archive as an example of the right kind of collaboration. With the St. Thomas team working directly with people from the Voorsanger firm, she noted, a representative sample of projects could be chosen to be archived, and the Voorsanger team could help to make sure that files that they sent for archiving were in an easily-read format.

This collaboration is important. If long-term storage and file compatibility are the big-headline problems with digital design archives, they are far from the only ones. In this situation, as in many others, a hidden problem of resource allocation can come to dominate. Voorsanger mentioned Tuesday night that his firm, being medium-sized, lacked the resources to create the kind of meaningful long-term archive of its own design process that a large firm like Skidmore, Owings & Merrill could maintain. The University of St. Thomas Department of Art History, able to provide expertise, time, and digital (and physical) storage space, was able to step in and fill a gap, in the process creating a model for ways in which smaller architectural firms and educational institutions can form partnerships to archive design materials. To this end, the process of creating the archive has been well-documented so that it can be shared with other institutions embarking on similar projects and partnerships, thus establishing an educational resource potentially as valuable as the Voorsanger Architects Archive itself.

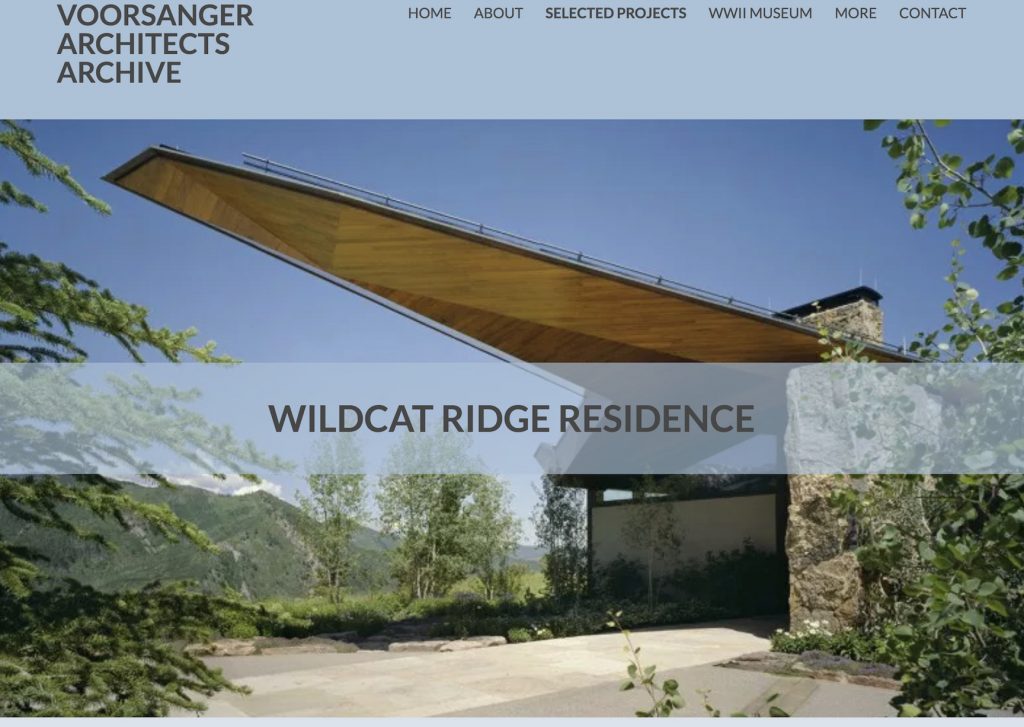

The digital incarnation of the archive is accessible through a website, VoorsangerArchive.org, and can be navigated by browsing by project or a robust search function. Archival objects include scanned documents, digital images and design files, informational records on physical models in the collection, and specially-created short video clips, dubbed “fragmenta,” that provide brief overviews of archived Voorsanger projects. The usefulness of this archive to students of design, architecture, and architectural history is self-evident, allowing researchers a powerful glimpse behind the curtain at the iterative design process behind 25 Voorsanger projects, including the National World War II Museum, the Wildcat Ridge Residence, and a redesign of control towers for La Guardia Airport.

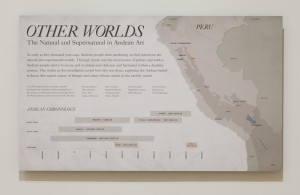

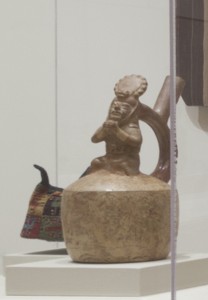

One challenge with Tuesday evening’s event lay in how to give a digital archive an exciting, engaging presence in the physical world; to this end, Department of Art History Gallery and the lobby of the O’Shaughnessy Educational Center were filled with technology for the evening. A virtual reality rig let visitors “walk” through immersive renderings of the plans for the National World War II Museum. Students with iPads circulated through the post-event reception, allowing attendees to browse the archive on the spot. A video screen displayed fragmenta on a loop. And archival physical models and photographs were on display, driving home the wide array of information available in the archive.

View of Preserving the Present exhibition. Photo by Mike Ekern, University of St. Thomas Photographer.

National World War II Museum display, part of Preserving the Present exhibition. Photo by Mike Ekern, University of St. Thomas Photographer.

Aside from its value to scholars and utility as a model of public/private archival cooperation, the Voorsanger Architects Archive allows the Department of Art History to provide practical, real-world experience to students in the growing field of digital humanities. Digital archiving is an important concept outside of the academy and architecture; museums and libraries now also find themselves struggling to maintain, protect, and exploit larger and larger bodies of digital records and archives (and, increasingly, born-digital art objects). For a department that keeps a steady eye on the practical realities of the museum world, the ongoing learning opportunity involved in maintaining, expanding, and using this archive is invaluable.