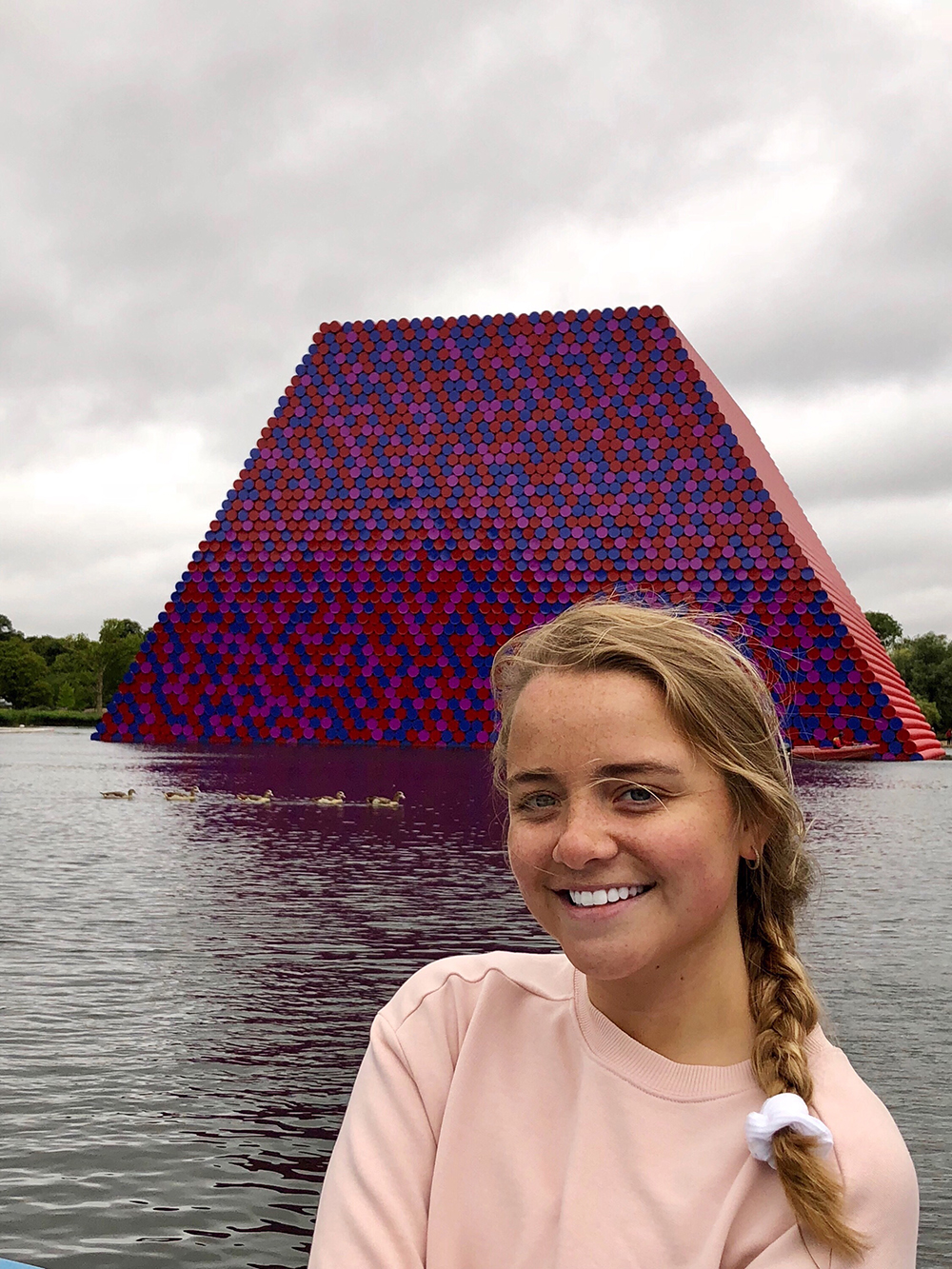

Tove Conway in front of the Royal Academy of Arts where John Constable and J. M. W. Turner studied. Tove will present her research at the Inquiry at UST Poster Session on Tuesday, October 2, 2018.

Tove Conway is an undergraduate English and Environmental Studies major currently completing research for her Sustainability Scholars Grant. Her research paper is titled, “The Evolution of Environmental Art: Visualizing the Relationship Between Humans and Nature Since the Nineteenth-Century.”

I am beyond thankful for the opportunity to travel to London, England, for my research on environmental art. Receiving a research travel grant from the Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program, the University of St. Thomas Department of Art History, the University of St. Thomas Department of English, and the University of St. Thomas Department of Geography and Environmental Studies made this trip a reality. The purpose of my trip was to experience and study three styles of environmental art in person, which brought my work full circle.

“Art takes nature as its model” –Aristotle

The facade of the National Gallery, London

My research is blowing me away… across the world in fact! I studied art history abroad in London with Dr. Victoria Young and Dr. Heather Shirey in 2016, but I was ecstatic to return for a whole new adventure. Brimming over with history and culture, traveling to London for my research was a dream come true. The top stops on my itinerary took me to museums and to natural settings alike, such as the National Gallery and Hyde Park. Walking in and out of galleries and parks allowed me to feel and see the evolution of environmental art beneath my feet and before my eyes.

The entrance to the National Gallery’s exhibition, “Thomas Cole: Eden to Empire”

Panning from an image of thick black factory smoke during the Industrial Revolution to small green spaces of bustling New York City and London shows how we are physically changing our planet. Likewise, environmental art reveals how and why people personally responded to these changes through the years. In my research I break down the Environmental Art Movement into three phases: landscape paintings, earth art, and urban ecological art. Sketching landscape paintings at the National Gallery and Tate Britain, walking through the cobblestone courtyard of the Royal Academy, and being within arms-length of Christo’s vibrantly colored London Mastaba personally introduced me to the true power, passion, and hope that environmental art holds.

Thomas Cole, View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm—The Oxbow, 1836, oil on canvas, 130.8 x 193 cm., The National Gallery, London

Unfortunately, photography was not allowed in the gallery, but take my word for it that the National Gallery’s exhibition, “Thomas Cole: Eden to Empire,” was breathtaking and visually dramatic. It was spectacular how the visible rise and fall of brushstrokes on the craggy American landscapes were congruent with Cole’s reoccurring theme: the rising and falling of human empires. Seeing The Course of Empire series up close seemed to create a short story between nature and humans. The five paintings evolved from a savage state to inevitable destruction and desolation in the name of human progress. Meanwhile, across the room, The Oxbow painting portrayed a question mark-shaped river, perhaps asking if it is possible to avoid this kind of ending. Turning slowly in the middle of the exhibition to create a panorama of Cole’s paintings, I felt that Cole had preserved parts of America’s identity in his paintings, and also left a warning of human destruction.

Christo’s London Mastaba on the Serpentine Lake in Hyde Park, London

On my last day in London, I walked from the Royal Academy of Arts to Hyde Park to see Christo’s London Mastaba. Christo is an environmental artist who is known for constructing temporary and controversial pieces of art using metal oil barrels or fabric—industrial materials lacking artistic function. Christo’s Mastaba was 66 feet high and consisted of a whopping 7,506 oil barrels. I was able to rent a paddleboat for an hour and slowly gravitate towards the blinding red, mauve, and blue barrels that were juxtaposed against the natural tones of Hyde Park. Sitting ten feet from the sculpture, I thought about how Christo’s art focuses on human intervention and conflicting areas between urban and rural or natural and artificial. To me, this piece was very special to behold because I consider it a hybrid between earth art and urban ecological art. It is temporarily placed in an urban green space in London, but it also engagingly interacts with the natural Serpentine Lake and its ecosystem as an earth art piece would.

A small model in the Serpentine Gallery’s exhibition, “Christo and Jeanne-Claude: Barrels and The Mastaba 1958-2018”

After studying the London Mastaba up close, I continued walking through Hyde Park to the Serpentine Gallery to see Christo and his late wife Jeanne-Claude’s exhibition, Christo and Jeanne-Claude: Barrels and The Mastaba 1958-2018. The exhibition was laid out as a timeline of their work with barrels—representing small models of trapezoid mastabas and blown up images of their large-scale environmental art projects. The exhibition ended with the bright sketches and photographs of the London Mastaba, their first large-scale sculpture in the UK and only on view for the summer of 2018.

London was calling, and my research answered. I am so thankful for funding from the Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program and the English, Art History, and Geography and Environmental Studies departments. Environmental art has the potential to challenge the status quo and spark change through our increased awareness of environmental degradation, and I believe my research runs parallel to this mission. Traveling to London allowed me to truly visualize and experience the relationship between humans and nature in art, and then personally contribute to modern sustainable development.