William Barnes is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Art History. His research interests include the Pre-Columbian cultures of the Americas, particularly those in Mesoamerica and the Andes. His principal research focus is upon the imperial Aztecs of Central Mexico and how their art intersects with ritual and the Mesoamerican calendar. He is currently teaching a course on the art of Mesoamerica, to be followed in the fall by a course on the early colonial art of Latin America.

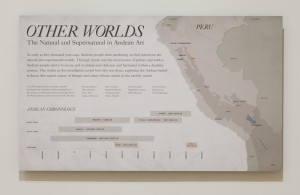

On a cold day in November, a number of UST graduate students accompanied me to the Minneapolis Institute of Arts (MIA) to talk about ancient Andean art and culture with a wonderfully receptive group of MIA docents and guides. For the most part, the students were presenting research they had undertaken in their 2014 spring semester graduate seminar entitled “New Research in the Ancient Andes.” Instead of standing behind a podium and reading from notes while PowerPoint slides fly by behind them, Katherine Joy, Zach Forstrom, Clare Monardo, and Nicole Sheridan were free to walk around gallery 255 and point to concrete examples of Andean art while discussing their salient features and historical context. Not only were they able to address the actual objects from their graduate studies, they also discussed what initially drew them to the works and why they were chosen for this installation — as they, along with eight of their graduate colleagues, had actually curated the gallery 255 installation from the extensive Andean works held in the MIA’s collection. Entitled Other Worlds: The Natural and Supernatural in Andean Art, the installation, on view until April 26, was almost entirely the work of that spring seminar class.

The graduate students selected works related to a number of important themes that the seminar discerned during their study of the broad scope of artistic production in the ancient Andes. These included “Andean Elites and Rulers,” “Feasting and Ritual,” and “The Natural and Super-Natural Worlds,” the final being the category from which the installation title was drawn. In the grouping of their chosen works, the seminar participants intended to show how Andean art was used to illustrate social differentiation, aspects of ritual and political obligation, and the role that depictions of the natural world and the supernatural realm played in legitimizing political authority and maintaining balance and harmony between all levels of the Andean cosmos.

- Zach Forstrom

- Katherine Joy

- Clare Monardo

- Nicole Sheridan

The works are strategically placed so that the viewer can physically walk one through the central ideas of the exhibit’s organizers. On the title wall hang two textiles, a central art form of the Andes whose design cues informed almost all other art forms and designs of the region. When worn, these textiles served to distinguish its wearer from other individuals in the region or communities. The one to the left is a 19th century Aymara llacota (a mantle worn by both men and women) likely woven on a traditional backstrap loom, while the other is a much earlier Huari elite tunic, likely worn by a member of the ruling class. Its elaborate design contrasts with the simplicity of the later Aymara piece, with its stylized depictions of Huari men bearing puma or jaguar-like attributes. The small hats worn by many of these figures are the very same as the MIA’s example 8th-10th century CE Huari four-cornered hat placed in the vitrine right in front of the work.

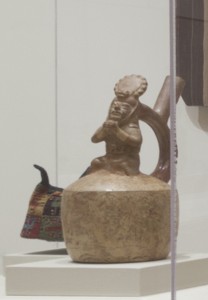

A Moche fineline pot is next to the small four-cornered hat. This pot depicts one of the famous Moche messengers who, aside from wearing animal inspired costumes, seemed to have served a role in carrying communications between Moche cities in the north coast of Peru (1-700 CE). From this central point in the gallery one can turn to investigate works that depict feasting and rituals, the objects of ritual (that allowed one to contact the supernatural), as well as depictions of super-natural creatures themselves.

- 19th century Aymara llacota (left) and Huari elite tunic (right)

- Four cornered hat and Moche fineline pot

- Moche fineline pot

I, and all the participants in the seminar, would like to extend our heartfelt thanks to Dr. Jan-Lodewijk Grootaers, Curator of African Art and Department Head, Arts of Africa and the Americas, along with his curatorial staff, registrar Kenneth Krenz, and the collections and exhibit design staff for the help they provided in putting together this installation. Despite the challenges it posed for them, this entire exercise wound up being a wonderful opportunity for our graduate students to develop a museum installation in such a hands-on and practical manner.