Pope Francis arrives in Canada | Catholic News Agency

This summer 21 people from three North Dakota Indian reservations travelled to Edmonton, AB. I had the honor of joining them. We travelled to bear witness as Pope Francis made a penitential pilgrimage across Canada. At every stop, the Pope apologized for the Catholic Church’s participation in the Canadian government’s effort to eradicate Indigenous culture.

Our group was present for three public Papal events around Edmonton: the apology at Maskwacis on July 23, the Mass in Edmonton the morning of the 24th and the Pope’s visit to the Lake St. Ann, the evening of the 24th. The Mass and the visit to Lake St. Ann were beautiful. Most impactful though was the event at Maskwacis.

From 1880’s through most of the 20th century, the federal government of Canada required all Indigenous children to attend residential schools, organized and sponsored by the government. If families would not submit their children were taken by force. The residential school staff, whether religious or secular, violently suppressed the speaking of Indigenous languages. They forced haircuts on boys with long hair. Connection with family was severely limited. Hygiene was poor, as was the food. Physical and sexual abuse were rampant.

Catholic leaders in Canada engaged the resources of the Church in the operations of these schools, deploying religious orders to carry out the task. The goal was ostensibly education, but in fact was the destruction of Indigenous culture. The efforts of the government and those who aided it would later be described as “cultural genocide” by the Canadian Truth and Reconciliation Committee established to confront the historic injustice of these schools.

Most of the members of our group were survivors of residential schools in the United States. While traveling to Edmonton, the travelers were invited to share why they had accepted the invitation to make the journey. Most who spoke shared stories of suffering and abuse.

The nature of the residential school system in the United States was not identical to that of Canada. Both were primarily concerned with the elimination of traditional Indigenous culture. Where Canada used overt force, the United States manipulated tribal communities by making the reception of treaty-promised resources like food, housing, education, and medical care conditions of sending children to state- or church-run residential schools.

At a time when many European immigrants were looking to integrate into American culture as quickly as possible, Indigenous were expected to do the same. Members of our group shared stories that are familiar to anyone aware of the history of the residential school system. Hearing them tell of the abuse shook me out of the insensitivity of shallow familiarity. We could see these elders here and imagine them then, children as innocent and uncomprehending as my 6 year old niece, thrust into circumstances entirely foreign and terrifying. One elder shared her story of arriving at the school and being violently punished every time she spoke her language, the only language she knew. She could say nothing as she had no way of expressing herself that would not lead to punishment. Her story of abuse pivoted in an instant to subversion and defiance when she said that even as the religious running the school tried to make her forget her language, she did not. The children would secretly speak to each other in their own language. Older children would comfort the younger, especially the newest arrivals to the school, as they learned to conform to the residential school system.

We arrived in Maskwacis early, as the crowds were expected to surge to as much as 15,000. In the end, this was a vast overestimation. The site of the meeting was a powwow arena, a feature to be found on reservations across North America. Those who made the journey from North Dakota later emphasized how important this was to them. That Pope Francis made his apology in the dirt, as it were. Indeed it was in the dirt. Powwow grounds are not used for religious ceremonies, but for a celebration of culture. At summer powwows across the Great Plains, as the sun begins to set, one can readily see rising dust from the movement of dancing feet striking the prairie soil.

There is also a note of defiance in meeting at a powwow arena. The culture celebrated here is the very culture the Church had worked to eliminate. The peak, to my mind, was the moments after the Pope arrived at the arena. The Holy Father took his seat on the dais. Shortly thereafter, the chiefs, leaders and delegations processed in in a “grand entry”, a normal part of a powwow. It is an egalitarian moment wherein everyone present is welcome to dance into the arena, regardless of dress, race, or culture of origin. It is a way for everyone to actively participate in the celebration. In this specific context, the grand entry was supposed to be limited to chiefs, leaders, and tribal delegations. In point of fact, no one who got up and stood in line was denied a place in the procession. This was clearly demonstrated by the fact that the members of our group from Standing Rock simply got up, joined the grand entry, danced in with everyone else- no permission, no questions. At the conclusion of the grand entry, immediately prior to the Pope’s apology, a victory song was sung. Drummers drummed and sang, dancers in regalia danced. It was a song of victory for surviving. After centuries of oppression and forced assimilation, they had persevered. It was a subversion of the narrative of who “won”. Immediately following the song of victory, the Pope began his apology for the Church’s role in Canada’s effort to eliminate Indigenous culture.

As the Pope offered his apology, most listened in solemn silence. The Pope spoke in his native Spanish and an interpreter presented his words in English. Around me, sobs could be heard, but most responses were subdued. As his apology continued, silently shed tears could be seen on the cheeks of some. But many received it with little or no response at all. For most, this was not a cathartic moment. It was a time to listen and judge. Is this sincere? Is this enough? Does it acknowledge the full nature of the horror hundreds of thousands of children experienced? In the end, it could not. Nothing could. But it was a substantive step toward justice and healing. The Indigenous community no longer needed to carry the memories of their suffering alone. Because the Pope was there, the world was listening and now knew what they had endured.

For some Indigenous leaders, it was the culmination of decades of work with the local bishops. The Church in Canada had been in dialogue with Indigenous leaders for years in a hope to build ties and develop trust. For those leaders, this moment represented a very significant step in a long unfolding process. For many, though, and most of the world, the horrors of the residential school system in Canada is a relatively new, something they were just beginning to process. This tension was clear when, after the Pope’s apology, Chief Littlechild, himself a residential school survivor, presented Pope Francis with a headdress. The gift was a natural expression of his gratitude and respect to the Pope. It communicated that the Chief recognized Pope Francis as an honorable leader. Chief Littlechild has been involved in this work for decades. For many, many others, though, his gift was incomprehensible, even a betrayal.

The next day former National Chief Phil Fontaine spoke to the crowd gathered for Mass in the Commonwealth Stadium in Edmonton. He was one of those who had been working with Canadian bishops for decades to bring to light the full horror of the residential school system. He spoke to Indigenous people and encouraged them to heal. And for healing, he said, there must be forgiveness. He spoke without notes and from the heart. But not everyone is where he is. Many are still learning about the facts of what transpired; forgiveness is distant. Like Chief Littlechild, Chief Fontaine is regarded as a sellout by many for his willingness to engage in dialogue and calling for forgiveness. The journey to healing is circuitous and everyone walks it at their own pace.

On the bus ride back to North Dakota, everyone was invited to share their experience, positive or negative. All who spoke shared that they were returning home grateful they had made the journey. Several spoke of healing and feeling a sense of belonging in the Church. After everyone on the bus who wanted to share had done so, the elder who had shared her story of abuse for speaking her language asked if she could offer a prayer. She asked if she could do so in the language of her childhood, her people. While she prayed, I felt I was witness to God doing something very beautiful. On a journey sponsored by the Church, led by a priest, she prayed in the very language that the Church had worked to destroy. She prayed as a Native American and a Catholic.

The success of restorative justice hinges on providing those harmed with a space to give voice to the harm. There are formal ways in which this is done. Much more often though, this work is done informally within the network of relationships in our lives. As the hurt body is oriented to healing, so to is the hurt soul. The work of processing harm is as natural as the knitting of bones. Healing the broken heart requires an intentionality, though, that is not necessary in the healing of the body. So we talk about our suffering with those we hope will listen with attentive empathy. Such sharing furthers the healing that is occurring in our hearts. Empathetic listening is a gift we can offer one another, whether it be the formal sharing of a healing circle, the supportive care of family and friends, or a group of residential school survivors sharing their stories with one another as they roll across the Canadian prairie.

For me, it is in that sharing that Jesus revealed Himself most clearly on the journey. To witness my traveling companions share their stories, pray together over the days we shared, hear the Pope apologize, and return to their homes with a renewed hope and trust that God loves them only confirms the deepest beliefs I have about who God is and how he works. God looks with favor on his lowly servants. He casts down the mighty from their thrones and lifts up the lowly. He fills the hungry with good things and the rich he sends away empty. He came to the aid of his servants and he remembered his promise of mercy, as he does for all who cry out to him in their need. It was a blessed adventure, one I thank God I was able to join.

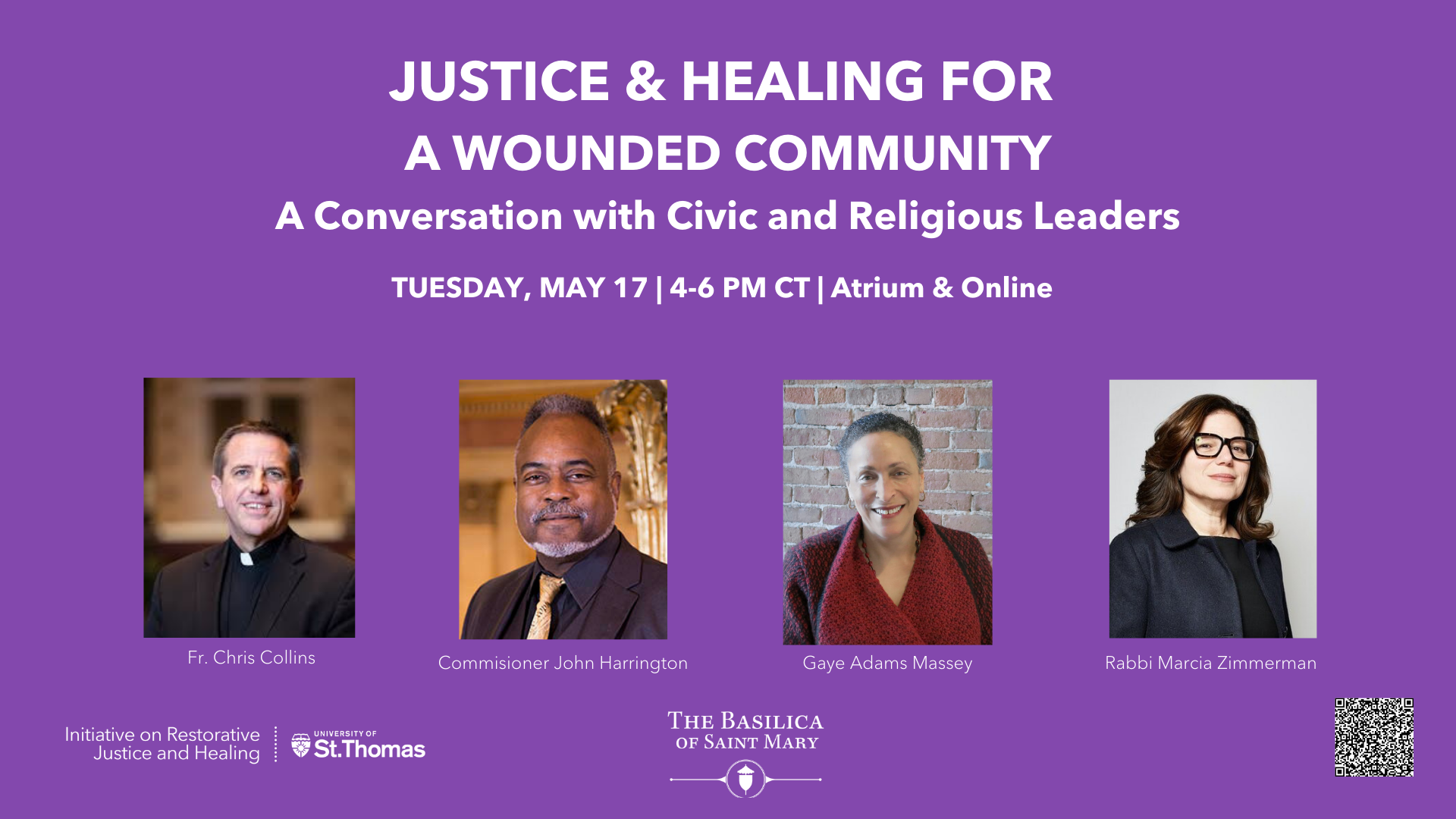

Monsignor Chad Gion, a priest of the Diocese of Bismarck, serves as pastor of the Indian Mission at Standing Rock in Fort Yates, North Dakota. Gion also serves as a chaplain for the North Dakota National Guard. Additionally, Monsignor Gion serves on the advisory board of the Initiative on Restorative Justice and Healing at the University of St. Thomas School of Law.