Keith Pille is a graduate student currently completing research supported by a Graduate Student Fellowship for Research on Topics Related to Women and/or Gender Issues from the Luann Dummer Center for Women. Keith also was the recipient of a Department of Art History Student Research Grant.

At the end of June, with the assistance of the Department of Art History Student Research Grant, I travelled to Brooklyn to talk to the cartoonist Ariel Schrag.

The author, with a panel of Ariel Schrag’s drawing of herself.

I wanted to ask her some questions about her work, and about the choices she made while drawing her autobiographical comics. I also wanted to ask her about what she has experienced having very revealing, personal comics out in the world. What was it like having intimate parts of her life on view for strangers, especially when said strangers had a very low barrier to getting hostile feedback back to her?

Ariel Schrag

This interview was part of an independent study project I’ve undertaken with Dr. Shirey, in which I’m examining the work of three women who draw autobiographical comics. Aside from Ariel Schrag, I’m talking to Julia Wertz, a California-based cartoonist whose work is widely praised and has appeared in the New Yorker; and to Deena Mohamed, a woman living in Cairo who uses superhero comics to examine her experiences in a coded fashion. I’m particularly interested in whether the spectacularly toxic misogyny that infects the internet—and you can’t make comics in the 21st century, or at least can’t have anyone read the comics you make, without a hefty internet presence—affects their work.

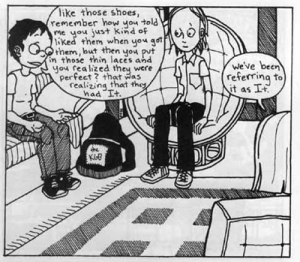

Ariel Schrag very nicely agreed to meet me in a cafe in Brooklyn. She was very friendly, funny, and easygoing; she was a great interview. One of the things I most wanted to ask her about was a technique she uses in her comics: when depicting her normal, day-to-day life, her style is simplistic and minimalist, often described as “cartoony.”

Schrag’s standard “cartoony” normal style

Periodically, though, when a character is fantasizing or dreaming, she shifts into a detailed, more realistic style with more natural proportions and perspective.

Schrag’s “dream realism” style

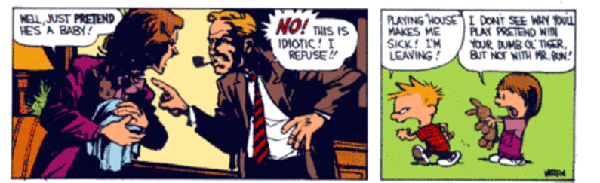

When I asked her what her thought process behind this was, she surprised me by describing the move entirely in terms of influences, saying that she was borrowing the idea from Bill Watterson’s comic strip Calvin and Hobbes, specifically some strips where Calvin and his friend Suzy are playing house (against Calvin’s will) and Waterson renders the panels in a photorealistic style.

Calvin and Hobbes panels showing Watterson’s “realistic” and “cartoony” styles

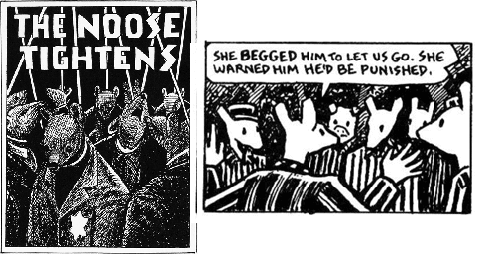

She also cited a section in Art Spiegelman’s Maus where Spiegelman similarly styles for a section to draw emphasis.

“Realistic” and “cartoony” styles in Spiegelman’s Maus

I was struck by her focus on influences—that isn’t a line of inquiry that I’ve heard artists talk about as a student of art history. But it is a line of inquiry that I’ve heard a lot before in music writing. I spent several years as a music journalist, and during that time had approximately 6,000 conversations with Twin Cities bands that included some variation of “so who are your influences?” It’s a topic that seems to emerge in all music writing (well, rock music writing; nobody ever seems to talk about Mozart’s influences). And the thing is: influences came up right away in my other interviews, too.

Which leads me to a theory: I think there’s a really interesting parallel between self-produced indie autobio comics and low-stakes music scenes. Both are artistically democratic situations where pretty much anyone with something to say can participate; formal training is rare in both cases (and none of the three very talented and accomplished cartoonists I’m talking to have any formal training), with people instead getting enthused and largely teaching themselves. I don’t think it’s much of a reach to say that self-taught artists are naturally going to lean heavily on influences from the material that got them excited to begin with.

We talked about several other interesting comics-technique things, but they’ll have to wait for the paper. I’d like to use my remaining space here to talk about the other side of our conversation: the part about reception, harassment, and misogyny.

My initial theory for this project was that the women I’m studying may have received toxic, misogynistic feedback from men (especially online), and that this may have been affected their artistic choices. To my surprise, Schrag said that this wasn’t really the case with her, that she hadn’t gotten much of what she would describe as misogynistic reactions. Rather, she said, when she’s received negative feedback, it was often from within the LGBTQ community and took the form of intracommunity discussions (which she said was great and welcome). She, knowing the focus of my project, said at one point, “I’m sorry I haven’t been harassed more! But I’m also glad.” (Like I said, she’s very funny).

Later, though, she described a phenomenon that she didn’t want to call misogynistic harassment, but which definitely sounded to me like bad behavior centered around gender: that of men (including, in at least once case, a man in prison) reading her comics and getting creepily over-familiar and lecherous (although she wanted to point out that she’s also gotten a lot of wonderful, thoughtful feedback from men as well, even a different man in prison). Schrag’s comics focus heavily on her experience in high school as she discovered that she was a lesbian; as such, there’s a lot of sex in them. Most people understand this is part of the story she’s telling, she says, but it does lead to some creepy emails. “When I wrote the comics, I never had a goal for them to be titillating; I don’t think it ever even occurred to me that they would be. And I think that was naïve. And now as an adult, the idea that an adult man might read my comics with a prurient interest does disturb me to some extent. But there’s nothing I can do about it,” she said.

I asked her if it felt strange to have so many details of her life out in the open; for instance, when we sat down, I knew all sorts of intimate details about her life, even though we’d only exchanged a couple of emails. She said it didn’t feel strange at all, since her comics add up to a story that she has complete control over. “I guess it’s a little weird, but it’s such a controlled version of a story of my life, and it’s something that I know anybody could read,” she said. “I don’t feel exposed per se, because it’s something I chose to put out. It’s not the same if someone were to read my diary.”

Panel from Schrag’s more recent comics work

We talk a lot in art history about artists using their work to create and assert their identity; Schrag’s statement about her comics being a controlled version of her life strike me as a perfect example of this.

If you want to hear more about Ariel Schrag, Julia Wertz, Deena Mohamed, and my general thoughts on autobio comics, come to the grad symposium in September!