What if traditional Chinese paintings of identifiable places relate what the artists or patrons actually experienced at the site? This seems a basic question. Yet, it has not been a focus of study in Chinese landscape painting scholarship. This query lies at the core of my research. In my work, I argue that an entire subset of seventeenth-century paintings relates the visual experiences of traditional Chinese travelers and tourists. I was offered the opportunity to present my ideas to an international group of scholars last spring in Berlin.

The DFG (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft) Research Group “Transcultural Negotiations in the Ambits of Art,” invited me to present a paper at their international conference “The Itineraries of Art. Topographies of Artistic Mobility in Europe and Asia, 1500-1900,” at the Freie Universität Berlin, in late May. The conference organizers sought to “investigate the role of itineraries and their crossroads in Europe and Asia as an organizing principle of artistic exchange.” Over the course of three panels, the conference group examined various “itineraries of art” as channels of communication in order to “explore their implications as modes of artistic experience.” I participated in Panel B, “Symbolic Itineraries and Topographies – Framing Roads and Routes.”

My paper focused on the seventeenth-century Chinese topographical paintings I have been researching. Over the course of China’s three thousand years of painting history, artists developed a variety of ways to depict specific places, from individual scenes to journeys through landscape that involve several scenes, creating a panorama. Scholars of Chinese art have discussed topographical paintings of this type as religious, political, social, cultural and stylistic narratives of their creators and audience. In these readings, however, the painter or patron has served as the narrative focus, while the surrounding landscape has been interpreted as a backdrop through which the focal person moves. My lecture reversed this priority. I still examined the focal person as an important element of the work. However, I identified the journey landscape as the active agent of the painting’s narrative. I believe this reading to be useful because it allows the landscape to take center stage as the primary player within the painting. Now it is the landscape, rather than the person, that narrates the journey and explicates its meaning. I have labeled landscape journey paintings that lend themselves to this reading “geo-narratives.”

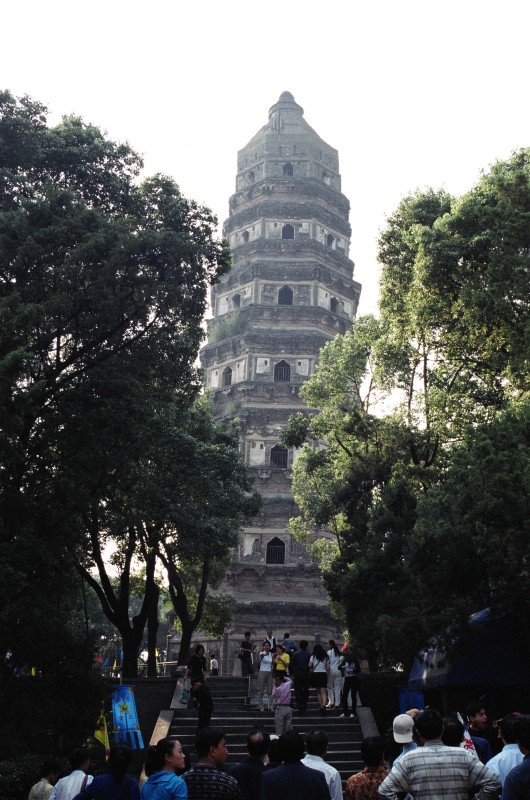

This new type of study requires a new methodological approach. My talk, then, was as much about introducing this approach, as it was about presenting an argument about a specific artwork. Art historians that focus on Chinese painting have traditionally developed their connoisseurship skills by studying a variety of paintings representative of certain artists and types. Knowledge of various calligraphic writing styles to read inscriptions, and the ability to decipher the red seals affixed to paintings that identify its artists and viewers, are other foundational skills of the field. In this century, scholars have also worked to place paintings within their religious, historical and literary contexts. My reading requires on-site study of topography and a consideration of the viewing experience of such topography to the interdisciplinary art historical repertoire. I locate and document the places depicted in the paintings I study. For example, I have examined the famous sites of Suzhou, such as Tiger Hill 虎丘, as well as those that have been not only forgotten, but also abandoned, like Mount Zhixing 支硎山 to understand artists goals and patrons expectations in renderings of them. My goal in such situations is to consider my own experience of moving through and seeing the geography of the sites in relation to their painted counterparts. These journeys reveal an entire site-painting lexicon utilized by Suzhou artists to represent the unique somatic and visual experience of the topography, architecture and views of each site. Paintings of Tiger Hill, for example, focus on the most well known sites at the summit of the mountain. This has been understood for some time. Only travelers sensitive to their experience of the mountain, however, note that the painted sites are illustrated facing the perfect location from which visitors might enjoy the many theatricals performed at the summit on festival days.

Remarkably, one is able to recreate many seventeenth-century journey experiences such as this throughout modern China. For example, in my studies of the sites around Kunming, Yunnan in southwest China, I have been able to find many of the sites illustrated in paintings produced in the seventeenth century. The famous Mount Taihua 太華山, for example, still boasts a monastery of the same name from which one may enjoy a view of the nearby lake lauded by countless visitors hundreds of year ago as “Endless Expanse of Blue” (Yibiwanqing 一碧萬頃). A plaque commemorates the view today. Understanding the implications of this extensive view allows us to read paintings that contain it differently. My goal was to convince listeners that by comparing the experience of an actual site such as this with its painted counterpart scholars can better understand how topographical paintings narrate the distinctive vision of individual players and their place in the world. A painter who illustrated the “Endless Expanse of Blue” from Mount Taihua, for example, conveyed not only the importance of this particular monastery in southwest China to the painting’s recipient, but he also implied an entire philosophical and literary tradition of sagehood keyed to expansive views. Only viewers who had climbed Mount Taihua could understand all of the implications of the view from this site.

Certainly, much has changed in China since the seventeenth century. Some sites have been geologically and culturally altered by time. Little original architecture remains. Tourism, the government and commerce have touched every site in some way. For these reasons I have not depended too heavily on the contemporary conditions of these sites. Even so, many have been carefully preserved or reconstructed, and the relationship of the updated architecture with the geography can sometimes present a physical experience roughly similar to that enjoyed by seventeenth-century visitors. Because care is also advisable in interpreting how a specific person or group received a certain view, I heavily qualify my visual experience of the sites with writings contemporaneous to the paintings. I use commentaries by seventeenth-century writers of gazetteer entries, travel records and colophons to balance my own modern reception of these sites and cross-reference these with analysis of earlier and contemporary site paintings indicative of traditional viewers’ ways of seeing and experiencing such works.

Using this variety of research methods I have developed a new reading of paintings that illustrate specific places. This reading takes these paintings to be “geo-narratives” that describe, through images and paratexts, a site-specific topographical journey in which the built and natural environment actively narrates the story and produces some kind of transformative effect on the viewer. Geo-narratives relate a wide range of geographical experiences, from visits to specific scenic locations to tours through groups of sites. Geo-narratives were structured to recreate a journey, commemorate an event, honor an individual, raise funds for a site, evoke nostalgia for the past, illustrate a philosophy, even summarize a life. The artists, subject matter and styles of geo-narrative paintings vary, but they all tell a structured journey-story through an identifiable landscape with an intended effect on viewers.