Jayne Cole is a graduate student in the Department of Art History. This past spring, she was awarded a grant from the Henry Luce Foundation and the Consortium for the Study of the Asias, to travel and do research in China during the summer. During her time in China Jayne interned at the Shanghai Museum.

This past summer, I traveled to China with Professor Elizabeth Kindall and classmate Floris Lafontant after receiving a grant from the Henry Luce Foundation and the Consortium for the Study of the Asias. It was my first attempt at grant writing, and the process tested my patience and writing abilities. I was grateful for Elizabeth’s help editing multiple drafts.

When the news came in the spring, I was ecstatic! The days slowly crept by until I left on June 21. I spent a total of 5 weeks in China: 2 with Elizabeth and Floris, and the last 3 by myself interning at the Shanghai Museum.

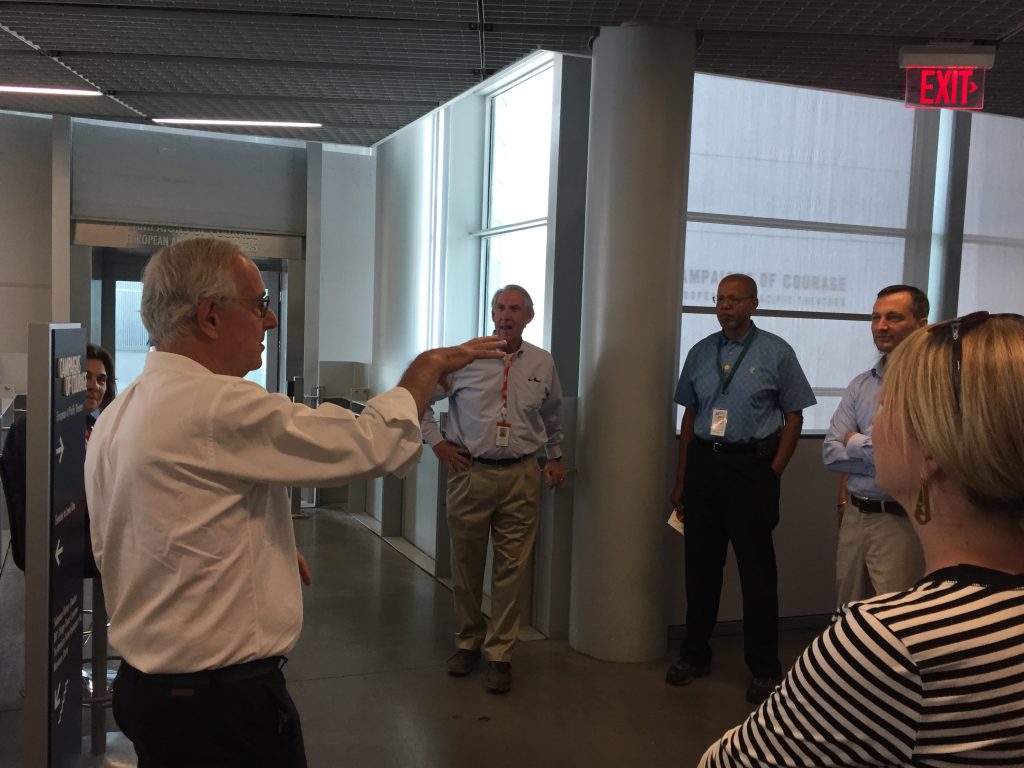

My summer research questions centered on understanding and experiencing Chinese museums. I used my internship at the Shanghai Museum to not only gain work experience, but also to better understand the Chinese museum world from behind the scenes.

Exterior of the Shanghai Museum

The first two weeks with Elizabeth and Floris flew by! We spent our time visiting exciting new sites, traveling to seven different cities, experiencing a plethora of museums, and eating wonderful food. I learned so many things during those first two weeks: what questions to answer when visiting a museum, how to conduct research, how to properly photograph a building, and how to ask new questions when something does not go as planned.

I was nervous when Elizabeth and Floris said goodbye to me in Shanghai after the first two weeks. My Chinese language skills are marginal at best, and I was in one of the biggest cities in the world! The only character I could read on a street sign was the one that said “road.” Not helpful. However, as soon as my internship started, I felt comfortable and at home.

My internship was in the Education Department of the Shanghai Museum. I was tasked with editing documents in English, and conducting a survey to foreign guests. I worked three days a week.

Inside the Chinese Ethnic Minorities’ Art and Crafts Gallery

The Shanghai Museum is huge! It has many different permanent exhibitions and has one of the largest museum collections in China. As a result, it is an extremely popular tourist location for both Chinese and international tourists. Many guests waited in line for over two hours to enter the museum.

The Education Department is located in the basement of the Shanghai Museum, and spread between many different offices. I often got lost trying to find the bathroom. I was the only international intern in the office, although they had about ten other college students volunteering. Many of the interns spoke English and attended school in the United States. I made friends quite easily, and still chat with many of them over WeChat, a communications app popular in China that is a combination of texting and Facebook.

Jayne and Venus

My boss paired me with a partner, a high school volunteer named Venus. She translated for me in the office, and also assisted me in my work assignments. We were fast friends, and I was grateful for her help. She often helped me order lunch.

Editing was harder than I expected it to be, but I enjoyed it. I primarily helped edit materials for the exhibition 100 Objects from the British Museum. It was really rewarding to work on something that will be used in the near future. A highlight was editing an official document used by the museum to negotiate future visiting exhibitions and cultural exchange.

Surveying was another interesting challenge. Using skills from a previous job I held at the Walker Art Center, I compiled a list of visitor-experience based questions (in English) with the help of Venus. We centered our questions around a specific exhibit focused on the different cultural groups in China. Venus and I administered the survey for four days and surveyed 48 people. After our surveying concluded, we analyzed the results and summarized them in a report for our boss, which Venus wrote in Chinese. It was a really fascinating project, and I learned a lot about Shanghai Museum’s international audience, the museum’s strengths, and areas of improvement.

Jayne surveying in the Chinese Ethnic Minorities’ Art and Crafts Gallery

In my spare time, I visited a lot of museums. My surprising favorite was the Propaganda Poster Museum. The museum was hidden in the basement of an apartment complex and challenging to find, but luckily I had a friend with me who had been there before. I was excited to find a poster I wrote about last semester in Heather Shirey’s class!

Jayne at the Propaganda Poster Museum

I left Shangahi the last week in July. I was sad to leave, but am excited to go back in the future! I left with a much better understanding of Chinese museums, and am excited to continue developing my research this upcoming semester.