Hanna Stoehr is a graduate student in the joint Master of Arts in Art History and Museum Studies Certificate program. Hanna was awarded a Department of Art History travel grant to support her Qualifying Paper research on contemporary artist Dario Robleto.

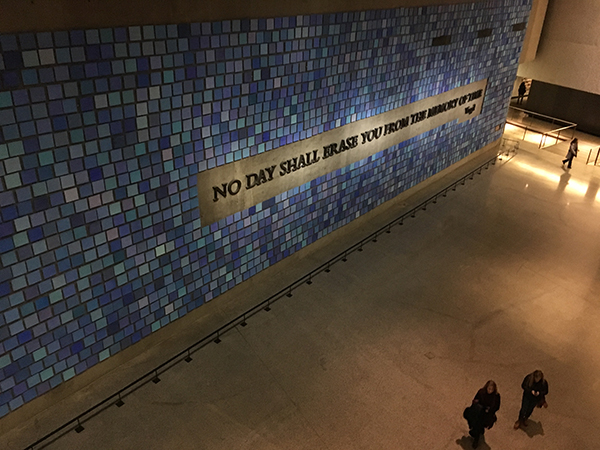

When I decided to write my Qualifying Paper on the language of death and mourning contained within the artwork of contemporary artist Dario Robleto, my first act was to look up where I might find his artwork in person. Unfortunately, his artworks arescattered throughout North American museums, and many of the artworks I was interested in viewing were not on display. Before resigning myself to viewing images in only printed publications, I looked into the three galleries that represent Robleto, and was delighted to find that his latest body of work, The First Time, The Heart would be on display at the Inman Gallery in Houston, Texas, from April 6 – May 26, 2018.

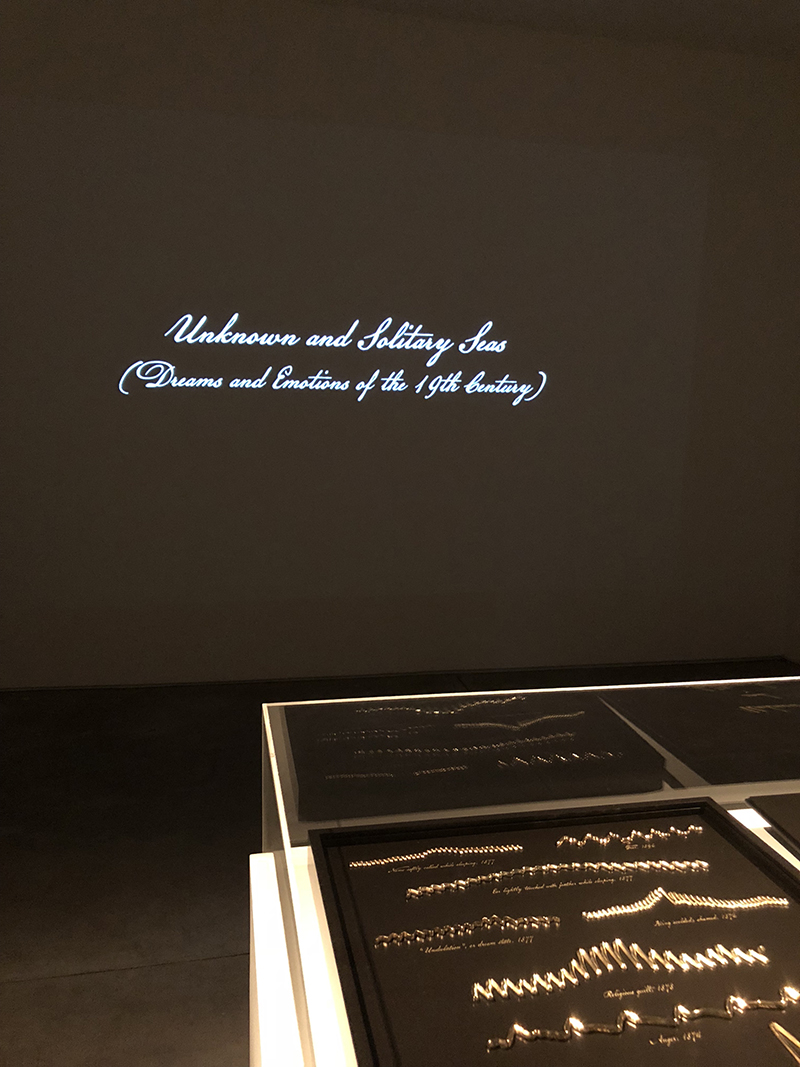

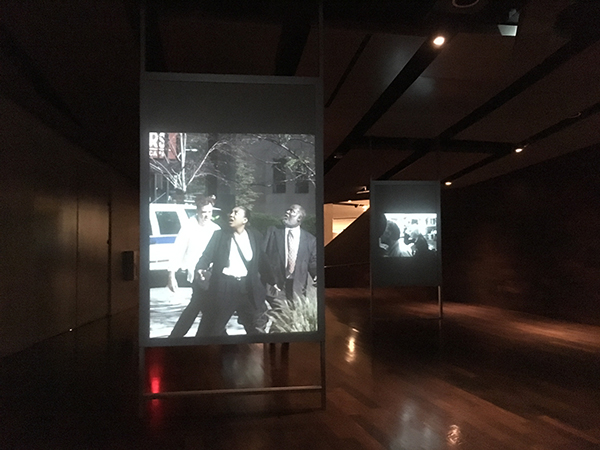

A view of Dario Robleto’s The First Time, The Heart at the Inman Gallery in Houston, TX.

Though the window for viewing the artwork was small, I believe that the success of my analysis hinges upon a deeper understanding of Robleto’s artwork that could only be achieved by viewing the art in person. Fortunately for me, the Department of Art History agreed and granted me the opportunity to travel to Houston to view this exhibition. Along the way, I also thought to add in stops at several other Houston museums to see how museums currently display death. I finally decided upon visits to the National Museum of Funeral History, the Houston Museum of Natural Science, the Museum of Fine Arts, and the Rothko Chapel.

An elaborate and large hair work wreath at the National Museum of Funeral History.

On my first day in Houston, I travelled directly from the airport to the National Museum of Funeral History. I was greatly interested to see how a museum that quite literally devotes itself to death elects to display and interpret the topic. For me, the National Museum of Funeral History was a bit of a playground. I was enamored by the display of antique hearses and delighted when I came across a small silver mourning spoon etched with birth and death dates and an image of the deceased. Most bizarre of all were the museum’s “selfie spots” which included one in front of a wax recreation of the body of Abraham Lincoln.

The National Museum of Funeral History’s “selfie spot” in front of a wax reproduction of Abraham Lincoln’s corpse.

However, I found that the various displays (there were fourteen to view!) were highly uneven both in terms of interpretive materials and, in some cases, obvious sources of funding. Exhibitions such as Celebrating the Lives and Deaths of the Popes and The Making of a Saint were beautifully and professionally executed, contained interpretive text galore, and took up some of the greatest square footage in the building. However, the Dia De Los Muertos and Egyptian Embalming displays were quite sad in comparison. The exhibitions looked uncared for, lacked interpretive text, and relied upon souvenir objects and craft store materials rather than historic artifacts. My lasting impression is that the museum’s ambition to present as much death history as possible was not matched by the museum’s resources.

Exhibition design for Death of a Pope was off the hook.

The following day I made my way to the Houston Museum of Natural Science. Looking back on my trip, I believe that I spent the most time at this museum, due in part to the great variety of exhibitions available. I spent a great deal of time in the Cullen Hall of Gems and Minerals and went a little crazy taking photos of the objects on display in the Fabergé: Royal Gifts exhibition. However, I had to recalibrate my museum brain when I entered the Cabinet of Curiosities exhibition. In three rooms, visitors were allowed to touch a majority of the objects on display. It took a great deal of effort to reach my hand into displays of taxidermy to touch—actually touch!—the body of a swan. I noticed that this reinterpretation of a historic Cabinet of Curiosities garnered lively conversation among my fellow visitors and instilled a great sense of mischief in me. Though it was allowed, I felt a bit giddy at the opportunity to touch a kangaroo pelt (note: kangaroos are incredibly soft and fluffy).

Visitors at the Cabinet of Curiosities exhibition at the Houston Museum of Natural Science.

When I entered the Museum of Natural Science’s Death by Natural Causes exhibition, I was quite ready to be wowed. Unfortunately, my hopes were dashed when I entered the exhibition hall and was immediately accosted by gimmick after gimmick that predicted my age of death (forty-six, if the fortune-teller is to be believed), showed me what I would look like if I suffered through the bubonic plague, experienced a rattlesnake bite, untreated malaria, and many other maladies. I left feeling slightly entertained, but no more educated or emotionally touched by the topic. My experiences earlier in the week had shown me that though death is a topic of interest in major museums, those museums blunder forward with notions of death as an unexpected terror that needs taming.

After answering a series of health and lifestyle questions, the Fortune Teller in the Death By Natural Causes exhibition at the Houston Museum of Natural Science told me I would live to be 46 years old.

After visiting the Houston Museum of Natural Science, I made my way to the famed Rothko Chapel, in which meditative artworks by the colorfield painter are displayed. When I arrived, I found the chapel was closed to the public, as a funeral was taking place. As I waited for the service to conclude, I briefly marveled that in my efforts to learn more about the business of displaying death, that I had just happened to stumble upon a funeral. When I was able to enter, it became apparent to me why a community would select the chapel as a place to honor the deceased. Just inside the door, there were texts from a handful of major Eastern and Western religions, marking the space as neutral ground. As I wandered about, looking at the paintings, people started gathering. Some took seats on benches, others settling down on meditation cushions. The space was silent but for the hum of the air conditioning, the settling of the other visitors, and my slow footsteps. Though the space had been cleared of all decorations from the funeral, I felt that the contemplation of death still hung about the room, charging it with the careful contemplation that I had sought during my visits to other death-centric museums and exhibitions in Houston.

A view of the Rothko Chapel’s interior, courtesy of the Houston Chronicle.

When I stepped into the Inman Gallery the next day to finally see Dario Robleto’s The First Time, The Heart, my visit to the Rothko Chapel was instantly recalled. Perhaps it was the similar color scheme and the slight humming of the air conditioning in the small space, but I believe that the exhibition experience was relatable because of the similar feelings and reactions I had during my visit to the Rothko Chapel. Earlier in my trip I decided to leave the visit to the Inman Gallery until the last day. After my contrasting experiences at the National Museum of Funeral History and the Houston Museum of Natural Science, I was ready to have a meaningful experience with death-centric art. I entered the grey gallery, noting groupings of framed artworks on the walls surrounding two cases containing pulse tracings cast in metal. An adjacent room held a book full of these metal pulse tracings, all recorded during specific quotidian experiences between the years 1854-1913. Audio recordings of those heartbeats surrounded me as I entered the room. I sat on the gallery floor, listening to each of the heartbeats in turn:

Name softly called while sleeping, 1877

Excitement; pulse leaping, 1886

Anger, 1874

Smelling lavender, 1896

Being scolded; shamed, 1876

Perfect mental repose, 1879

Flatline (dying of stomach cancer), 1870

Recordings of heartbeats and their sculpted pulse tracings displayed in the adjacent dark room under the title Unknown and Solitary Seas.

I did not get up from the gallery floor for a very long time. Though the exhibition was held in only two small rooms, I spent nearly two hours taking in each work of art (an etching of each pulse tracing), listening to each recorded heartbeat more than once. What I found was an exploration of the ways in which the heart is a site of humanity. It grows, lives, weakens, and dies. The First Time, The Heart was an exercise in reading empathy and human experience. This theme is common in Robleto’s body of work, and in the interest of my research, contains a great number of links to death and mourning. As I push forward with my Qualifying Paper, I am grateful to the University of St. Thomas Art History Department for providing me with the opportunity to dive deeply into my study of death and mourning by way of traveling to Houston to see the incredible Robleto exhibition.

A view of the sculpted pulse tracings created for The First Time, The Heart.

Michael Rainville, Jr. is currently in his second year of the M.A. Art History/Museum Studies Certificate program.

Michael Rainville, Jr. is currently in his second year of the M.A. Art History/Museum Studies Certificate program.

Jason Burnett is currently in his second year in the M.A. Art History program. This fall, he is enrolled in Museum Studies: Collections, Curation, and Controversy.

Jason Burnett is currently in his second year in the M.A. Art History program. This fall, he is enrolled in Museum Studies: Collections, Curation, and Controversy.

Jessy Saffell is currently in her second semester in the M.A. Art History/Museum Studies Certificate program. Last fall, Jessy was enrolled in one of the graduate program foundational courses, ARHS500: Methods and Approaches to Art History. Currently, she is enrolled in two seminars this spring: ARHS515: Asmat Museum and Beyond: Collections, Colonialism and Controversy – Exhibiting Non-Western Art and ARHS535: Seeing Otherness: Afropean Intersections.

Jessy Saffell is currently in her second semester in the M.A. Art History/Museum Studies Certificate program. Last fall, Jessy was enrolled in one of the graduate program foundational courses, ARHS500: Methods and Approaches to Art History. Currently, she is enrolled in two seminars this spring: ARHS515: Asmat Museum and Beyond: Collections, Colonialism and Controversy – Exhibiting Non-Western Art and ARHS535: Seeing Otherness: Afropean Intersections.